PEOPLE & PLACES: Assessing Shipwrecks: The Value of Preservation

People along the coast take notice when the graveyard of the Atlantic dumps one of its shipwrecks on the Outer Banks beaches. They stare at timbers that stick out like whalebones, poke around for clues to the vessel’s identity and gather to watch archaeologists conduct postmortem examinations.

“There will be a lot of beachcombers swarming around you,” says Nathan Henry, assistant state archaeologist with the N.C. Division of Archives and History.

Judging by the interest in wreck sites and relics, plenty of people are intrigued by the mystery and lore of the many vessels that sank off the North Carolina coast. But gauging just how valuable shipwrecks are to the general public is tricky.

East Carolina University researcher Calvin Mires hopes to shed some light on the issue. A staff archaeologist at the ECU Maritime Studies Program, Mires is considering how the general public treasures the maritime cultural heritage resource that shipwrecks represent. Using one-on-one interviews and mail surveys, he plans to evaluate how the public perceives shipwrecks and how much value is placed on preservation.

“We’re not trying to put a value on a shipwreck or say this is a monetary dollar amount,” he says. “What we’re really getting at is the preservation of shipwrecks as a whole.” His project, supported by North Carolina Sea Grant, is part of his dissertation for a doctorate in ECU’s Coastal Resources Management program. The results also will help government officials, educators and others recognize the benefits and costs of preserving maritime cultural heritage resources.

“Calvin’s study is being supported under the ECU/Sea Grant joint Maritime Heritage Fellowship Program,” says Michael Voiland, North Carolina Sea Grant executive director. “His winning proposal was of interest because it seeks to get at public valuation of historic resources — a factor that’s critical in how governments might support or invest in such resources in the future.”

PLENTY TO PRESERVE

There is plenty to consider. Historians say that more than 5,000 vessels have been lost in the 15,000 square miles of ocean off the North Carolina coast due to a combination of natural and human factors. Shipwrecks ranging from schooners to German U-boats span hundreds of years of history. Outer Banks residents and visitors have inherited a maritime heritage “as nch and historic as any in the United States,” Mires writes in an overview of his research.

“These archaeological and historic sites serve as a dramatic link to the region’s broader maritime heritage, helping to illuminate the critical role of shipping along the eastern seaboard and establishing sense of place in American history,” he notes. “Yet questions arise regarding how aware they are of this heritage, how connected they feel to it or identify with it and if they are willing to pay for its preservation.”

Most of the shipwrecks don’t contain buried treasure. They don’t have the mystique of pirate ships or the historical connections of Civil War vessels and German submarines ortheirvictims. A few sites — such as the wreckage of the Civil War gun boat USS Monitor off Hatteras and the remains near Beaufort that are believed to be Blackbeard the pirate’s flagship — have been widely publicized but most are largely unknown or overlooked.

Except for divers and researchers, most people never see a shipwreck up close unless one happens to be uncovered on the shoreline. For most people, Mires says, shipwrecks are little more than dots on a map.

As a staff archaeologist at the ECU Maritime Studies Reid School, Mires has done his share of hands-on work on shipwreck sites. He works with students and faculty and also takes care of equipment and administrative matters. But his current research takes him into town halls, local businesses, tourism promotion offices and to dockside meetings with fishermen.

SURVEYING ATTITUDES

Part of his project focuses on the academic and government experts involved in preserving shipwrecks. Questions are designed to transform individual opinions into a group consensus on various issues such as the major challenges in preserving shipwrecks, whether all shipwrecks are “historically significant” and what type of management is effective.

Mires expects there will be some controversial issues, such as whether recreational and sport divers should be allowed on wrecks and whether commercial activities should be permitted.

He’ll also quiz individual and focus groups for what they consider important about preservation, education and outreach for submerged cultural resources. Mires will include questions about who benefits from or enjoys shipwrecks now and who should. He wants to know if participants feel shipwrecks should be preserved and, if so, how? He also will ask participants to consider whether artifacts should be taken off a site or whether a site should be left as is.

Mires says he is not judging whether a viewpoint is good or bad. He wants to know how people perceive the role of state and federal government, divers and the general public when dealing with shipwreck preservation.

So far Mires has done some reconnaissance interviews to help determine how to proceed. He plans to have the work completed in 2011.

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS

Although it is still a work in progress, he is encountering strong views on the issue. For instance, while interviewing Outer Banks residents, the issue of shipwreck preservation becomes intertwined with beach access issues. People veer into discussions about federal restrictions on off-road beach driving in areas closed to protect wildlife, such as nesting shorebirds. “They really took off on that issue,” Mires said.

It is pertinent because the experiences with access shape people’s attitudes about preservation of shipwrecks. Mires says many suggest shipwrecks should be preserved as long as there is no regulation. Some respondents don’t mind the actual structure being preserved but do not want the water around it restricted.

“A common theme is: ‘We want preservation we just don’t want anyone to tell us how to do it,'” he says.

“There is a sense of paranoia,” he adds, “that once it (regulation) is here — state or federal — it never goes away.”

Despite the antigovemment attitude and strong feelings, Mires said people have been pleasant and helpful.

While shipwrecks are important, Mires says they are not considered by many to be as big a draw for tourists compared to recreation.

It helps to survey attitudes about government involvement and use of taxes during tough economic times because people are less likely to want to spend money to protect resources when money is tight. Mires says critics might argue that public attitudes during good economic times benefit from a “warm glow” toward public projects that is not realistic. “Right now it’s about as negative as I could get,” he says. “At this point that warm glow is hard to find.”

According to Mires, discussions about values often look at market values for maritime archaeological artifacts and the relevant effects such as treasure hunting, souvenir hunting and the antiquities trade or qualitative charactenstics. The primary focus of his research is to evaluate the public’s perceptions, attitudes and willingness to pay for the nonmarket values of heritage.

MORE THAN MARKET VALUE

The emphasis on excavation of artifacts, museum exhibits and tourism expenditures such as museum entrance fees and diving charters are often considered the only economic values of a shipwreck. Although they will be discussed to a limited extent, he says, his research will focus on the nonmarket values inherent in these resources that must be considered for the good of the resource and for sustainable use for future generations. Bequest value (the value of preserving a resource for future generations) and existence value (the benefit from knowing that a resource exists) are examples of these types of nonmarket values.

Mires, 35, took a roundabout path to the Graveyard of the Atlantic. He was bom in Alaska and grew up in Montana. He earned his bachelor’s degree in Latin and classical civilizations from the University of Montana in 1998, and his master’s in maritime studies from ECU in 2005. He initially taught Latin and Greek in Pennsylvania before coming to ECU as a student.

He has participated in research projects in Israel, Bermuda, Hawaii, Montana, the Great Lakes, North Carolina and South Carolina. Work with the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary on Lake Huron spurred his interest in the value of underwater cultural resources. He was intrigued that residents of the small town of Alpena, Mich., which has about 12,000 people, supported a heritage center that drew on the maritime history associated with the region that has more than 100 shipwrecks. He wanted to examine why people feel so strongly about shipwrecks.

A RECENT DISCOVERY

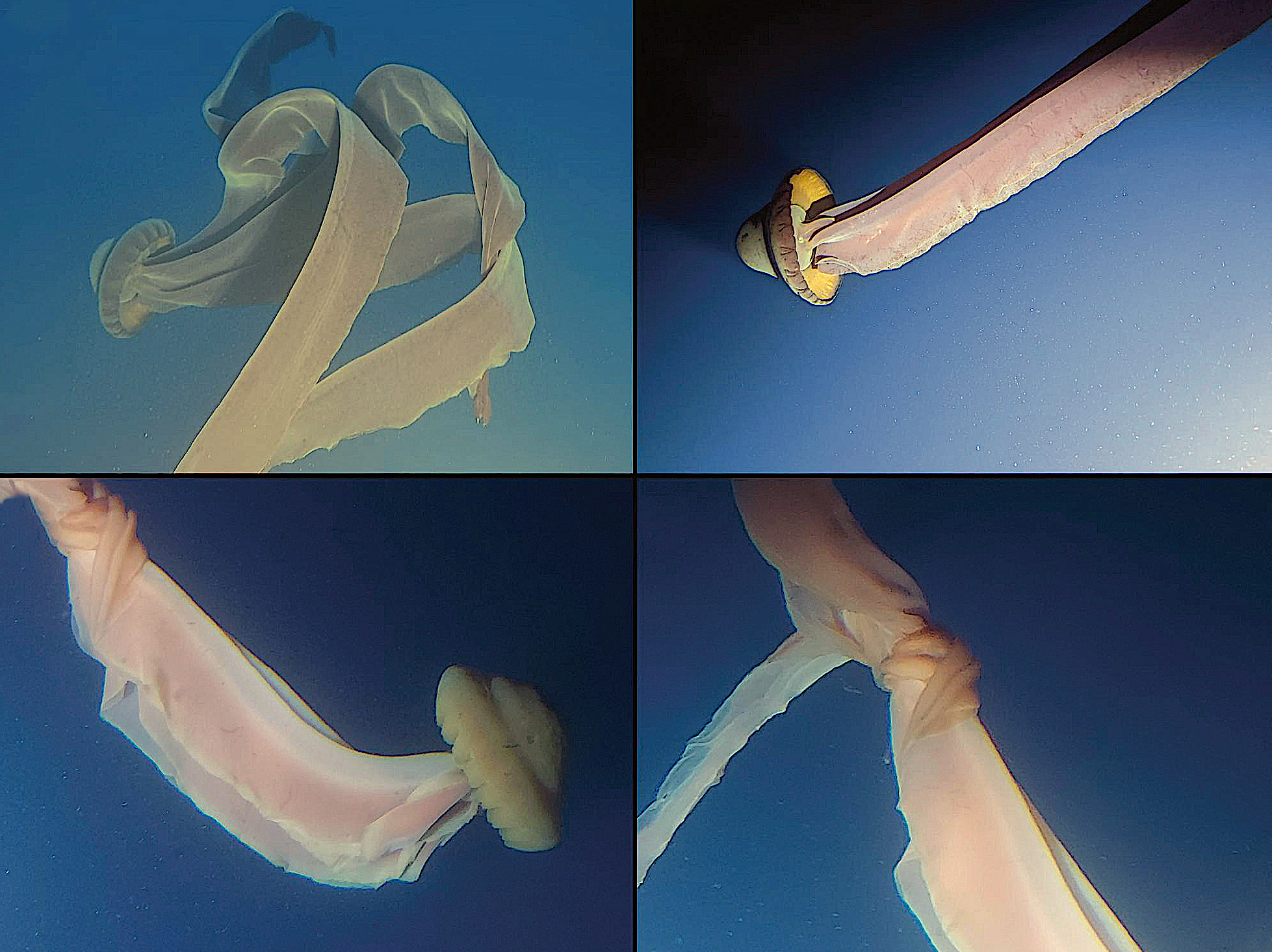

Ray Midgett of Southern Shores, a retired N.C. Department of Revenue auditor who is an avid beachcomber and amateur history buff, says he believes public attitudes toward preservation are positive. Midgett, who has inspected and photographed scores of shipwreck remains on Outer Banks beaches, says beachgoers often pose beside the remains and ask questions about the ships.

“My attitude is it (preservation) is worth every dollar you can put into it,” he says. State archaeologists credit Midgett with helping to save what could be the state’s oldest known shipwreck after it was uncovered by storms recently on the beach in Currituck County. Midgett found artifacts with his metal detector and also observed that wooden trunnels or pegs were used to fasten timbers.

Prodded by Midgett and others, state scientists determined that the ship construction and artifacts, including coins and lead shot, dated the remains to the Colonial era. Ten solid oak frames, planks 18 inches wide and numerous artifacts indicated it could have been a mid-1600s merchant ship.

Prior to the discovery of the Currituck shipwreck, the oldest shipwreck discovered along the state’s coast is the presumed flagship of Blackbeard the pirate, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, which sank in 1718. The wreck was located in November 1996 by Intersal, Inc., a private company.

State agencies initially moved the remains of the Currituck vessel off the beach to an area near the Currituck Lighthouse. In July, the 12-ton chunk was trucked 90 miles south to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum at Hatteras, where the wooden timbers will be treated to halt deterioration.

Midgett says preserving the battered shipwrecks is a way of preserving the coastal heritage. “They’re not making 1600s shipwrecks any more,” he says.

Henry, the archaeologist with the North Carolina’s underwater archaeology branch, says Mires’ work could help support efforts to preserve the state’s resources. “It will be a little ammo,” he says.

This article was published in the Holiday 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: