A Ferry Tale for All Seasons

Two blasts from the ship’s horn and slips away from the Cedar Island The Carteret slips away from the Cedar Island ferry dock to begin the two-and-a-quarter hour Pamlico Sound crossing. Destination: Ocracoke Island.

Moments before, families with kids, cats and dogs, hopeful fishing parties, Outer Banks residents returning from mainland business, and local commuters heading to their island jobs queued up for the trip. They’d come on motorcycles and bicycles, in cars, motor homes, and trucks pulling boats loaded with fishing gear — license plates from as far away as Canada and Kansas attesting to the lure of North Carolina’s coast.

Now on board The Carteret, passengers settle in to enjoy the excursion across the mirror-like sound under a cloudless blue sky. Some, new at the ferry game, cautiously step outside their vehicles. Two veterans pull deck chairs from the trunk and arrange them on the windy deck.

Another stretches across the front seat of her SUV with a pillow tucked behind her head and a paperback novel in hand — windows open to catch the steady breeze. Plants and shrubs for a seaside landscape are crowded in the rear compartment.

As we clear the dock, a young man pulls bread from a picnic basket. Greedy sea gulls swoop down to claim their prize from his upheld hand. Soon the gulls lose interest in the bread and return to the shore, now shrinking on the horizon.

It will be a while before the Ocracoke lighthouse comes into view, so there is plenty of time to walk about the ferry, chat with passengers, and simply enjoy the moving images of sea and shore.

Born of geographic necessity

There also is time to think about the evolution of the N. C. Department of Transportation’s Fen-y Division into one of the largest state-owned and -operated systems in the nation — second only to Washington.

Today, a fleet of 24 ferries operates year-round to transport more than two million passengers across seven water routes over five bodies of water. In addition, the division owns a dredge and numerous support vessels, maintains its docks and passenger service centers, and operates its own shipyard.

Born of geographic necessity, the state’s sophisticated ferry system provides much more than a pleasant way for tourists to “discover” coastal North Carolina. Ferries are an integral part of coastal culture and history, and continue to be the lifeline of many communities in the region.

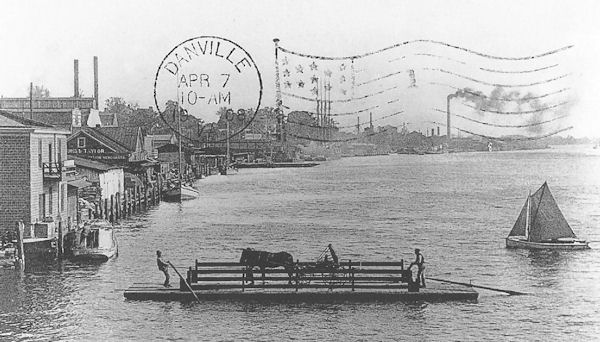

It is not hard to imagine Native Americans negotiating the complex system of rivers, bays, sounds and inlets in dug-out canoes towing rafts piled with freshly killed wildlife for their village’s winter cache.

Early settlers, too, depended on small watercraft and barges to ferry people and essential goods to towns scattered along miles of erratic coast line. No bridges connected the st1ing of Outer Banks islands with each other or the mainland, and few overland roads traversed the low-lying terrain.

As the coastal population grew, so did the need for food, medicine, trade goods and mail — as well as for a reliable means of communication with the world beyond watery boundaries. In the early 1900s, a ferry system began to take shape from private efforts to meet those needs. A tug and barge conveyance system linked Bodie Island and Hatteras Island across the Oregon Inlet. A wooden trawler-type fen-y soon was put on line.

The groundwork was laid for a state-supported ferry system when, in 1934, the State Highway Commission -now known as the Department of Transportation — subsidized the route to reduce the ferry tolls. By 1942, a fixed reimbursement arrangement with the ferry operator eliminated tolls on that route.

Similarly, in the early 1940s, a private ferry business across the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Manteo was established. When the captain-owner died, his family sold the franchise and two vessels, the Dare and Tyrrell, to the state in 1946.

The ferry system grew in concert with other coastal developments in the early 1950s, which included paving N.C. 12 from Whalebone Junction to Hatteras and establishing the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Larger capacity vessels and additional routes were launched to meet demands.

With expansion came the decision by the State Highway Commission in 1960 to create an independent State Ferry Operations office at Manteo. To provide more centralized service, its headquarters were moved to Morehead City in 1964. In 1974, it became known as the N.C. Ferry Division.

Responding to life and death emergencies

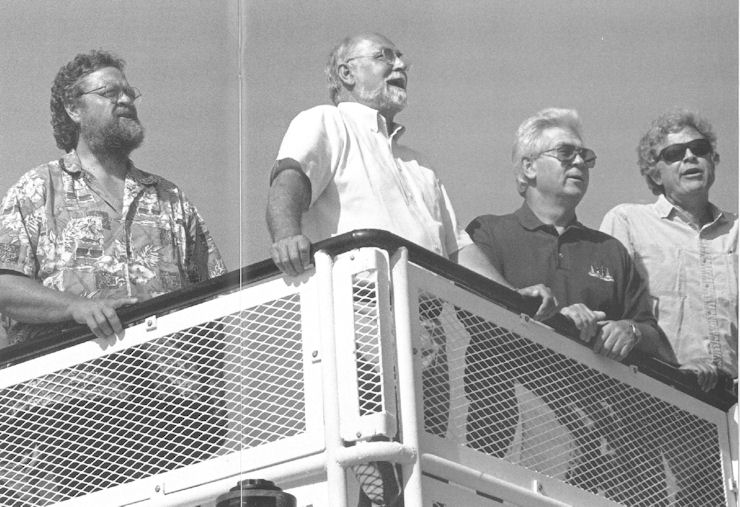

Ferry routes and vessel sizes have changed to meet transportation needs, says G.W. “Jerry” Gaskill, division director since 1993. Long before he came on board as director, Gaskill, whose family roots sink deep into Cedar Island and Ocracoke shores, understood that the ferry system plays a vital role in the day-to-day lives of coastal residents.

Gaskill also knows too well that the system plays a part in life-and-death emergencies such as Hurricane Floyd in September 1999.

State evacuation operations were hampered when a section of U.S. 17 between Chocowinity and Washington flooded, he recalls. Coordinating with the state’s emergency management team, Gaskill quickly moved four extra vessels into place on the Pamlico River at the Aurora-Bayview ferry crossing. For three days, state troopers diverted traffic from the flooded highway to Aurora. Thanks to round-the-clock ferry operations, some 8,600 vehicles filled with 14,000 anxious passengers moved to safer

and dryer U.S. 264 on the Bayview side.

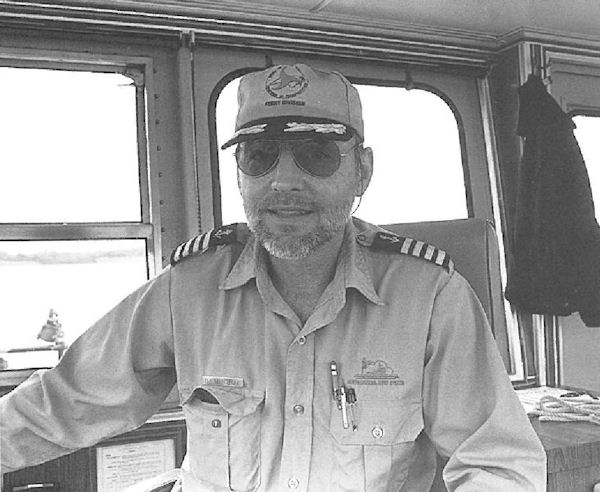

There were tense moments, recalls Captain Charles Piner. “It was the only way to get to the hospitals in Greenville where one family had a dying grandmother. The highway patrol allowed the family car to pass ahead in the line of waiting vehicles so that they could get there for their good-byes. Another woman in labor managed to make it to the hospital in time,” he adds.

Piner, a former tugboat captain, has been with the ferry division since 1996 — long enough to remember hurricanes Fran and Bertha. “Nothing has been as dramatic as Floyd’s flooding,” he attests.

That may be true, Gaskill says, but the ferry workers historically are the “unsung heroes” of coastal storms — assisting in evacuation efforts from Outer Banks communities, delivering food and medicine to stranded islanders, and unglamorously transporting refuse in the wake of such natural disasters. Ferries also completed the Outer Banks link while the Bonner Bridge at Oregon Inlet was closed for repairs after being damaged by a barge during a nor’easter in October 1990.

All emergencies don’t have happy endings, says Captain Sandy Mitchell on board the Southport. The former Navy and merchant seaman says his crew was called into action to help with the rescue of a capsized shrimp boat on the Cape Fear near the former Corncake Inlet. “We rescued the passenger on the boat, but the captain didn’t make it,” says a somber Mitchell.

Unexpected weather situations can cause any body of water to go from flat to four-foot waves in a half-hour’s time, Mitchell notes. But the Southport’s advantage is a state-of-the-art Voith Schneider propulsion system. An unconventional rudder and prop in one, its five blades can be varied in pitch, thrust and direction to enhance maneuverability even in the roughest conditions.

“We can keep running in wind when others have had to tie up at the dock,” Mitchell says.

The Southport-Fort Fisher route gives passengers another advantage -a view of the ruins of the Price Creek Light. Built in 1850, it is all that is left of a series of range lights used to guide ships along a Cape Fear River channel to the Wilmington port. During the Civil War, the lights were critical to Confederate blockade runners, but were destroyed when the Union troops took control of the coast.

Less dramatic, but important

Not all ferry routes have dramatic tales to tell, Gaskill points out. Each meets a particular need. The Minnesott Beach-Cherry a Brancy run serves a predominantly military population at the Cherry Point Air Station with two ferries making 72 daily crossings; the Aurora-Bayview ferry transports PCS Phosphate mine workers; and the Swan Quarter-Ocracoke ferry connects island residents to their Hyde County seat.

The Knotts Island to Currituck ferry was initiated in 1962 to provide transportation across Currituck Sound for youngsters attending county schools on the mainland. A 90-minute bus route formerly took the students to school via Virginia Beach and Chesapeake, Va. Now, middle and high school buses sail across the sound in half the time.

“Some of our classmates from the county think it must be exciting to ride a ferry to school,” says Jennifer Hicks, a student at Currituck Middle School. “But, for us, it’s kind of routine — except when we have rough weather.”

Her brother, Jeremy Gruzd, says that not much stops the fwy from delivering students to and from school. “Fog is just about the only thing that prevents it from going. In case of fog, the buses go the long route through Virginia,” he points out.

Otherwise, Knotts Island middle and high school students board buses in their neighborhoods and roll on the deck of the James Baxter Hunt, Jr. in time for a 7 a.m. departure.

Captain Gilbert J. Brickhouse recalls that the Hunt was put into service on the Currituck Sound in 1985 to replace the six-car Knotts Island. The growing Knotts Island population soon outpaced the capacity of the Hunt. In 1999, the Hunt was transferred to the Manns Harbor shipyard, cut in half, and 30 feet added to its middle. The overhaul doubled the ferry’s capacity — and saved the state millions of dollars in new ferry costs.

Brickhouse joined the ferry service in 1976 and has had his captain’s license for 15 years. He can’t imagine a better job, in spite of the inherent dangers — water spouts, lightening storms and smoke from burning marshes.

“lt can get pretty exciting,” Brickhouse says. “But nothing is more exciting than knowing that you are in a place to help kids. Some come on board in the morning with a frown on their faces. lf you can send them off with a smile, who knows, maybe they’ll make a good grade that day and feel a lot better about themselves.”

Ferries becoming science labs

As far as Gaskill is concerned, there are no limits to how the ferry division can serve North Carolinians. Ferries already offer unique views of lighthouses, access to remote communities, emergency evacuation assistance, and dredging operations to keep shipping channels open.

Soon select ferries will become research vessels thanks to a partnership with Sea Grant scientists from the Duke University Marine Lab, the UNC-Chapel Hill Institute for Marine Sciences, and the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). “Ferrymon” project leaders are Joseph Ramus, Duke professor of biological oceanography, and Hans Paerl, UNC Kenan professor of marine and environmental science.

Ramus says Ferrymon will use automated devices to monitor salinity, temperature, turbidity, chlorophyll and oxygen levels. The ferries also will collect refrigerated water samples to measure nutrients and other dissolved materials.

The monit01ing devices will sample natural water flowing into the sea chests on the Cherry Branch-Minnesott Beach ferry on the Neuse River, and on the Cedar Island-Ocracoke route and the Swan Quarter-Ocracoke route, both on the Pamlico Sound.

Coupled with other remote monitoring programs, Ramus says, the scientists hope to get a better sense of how the Pamlico — the most important fishery nursery in the mid-Atlantic — works.

“Ultimately, we will be able to construct predictive models, so that when there is an increase in nutrient input, we will know what the outcome will be,” Ramus says. “This partnership makes sense. Ferries are large stable platforms that can be utilized for efficient water-quality monitoring.”

Larry Ausley, ecosystems unit supervisor for DENR’s Division of Water Quality, says the short-term monitoring results will be of particular interest because of the nutrient loading from last year’s hurricane season. Scientists will watch closely to see what happens when the Pamlico waters are warmed by the summer’s heat.

Ausley believes the partnership with the ferry division will be a cost-effective way to conduct ongoing analysis of the surface waters of this large and important body of water in real time. Eventually, Ferrymon data will be available to the public on a Web site.

The Ferryman Project may cause Gaskill to rethink a Ferry Division promotional message that suggests “Looking for Discovery, Adventure and History? Call 1-800-By Ferry.” Perhaps it should say “N.C. Ferries: Looking for Scientific Discovery. Making History.”

For a closer look at ferry schedules, go to www.ncdot.gov/Ferry on the Internet.

This article was published in the High Season 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.