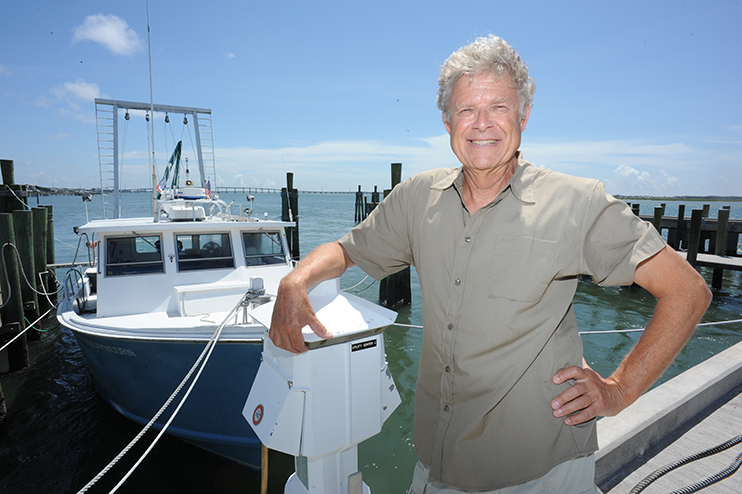

HARD-WORKING HODSON RETIRES JUNE 30: “What You See is What You Get”

Ron Hodson arrived in North Carolina in April 1973, with a fresh doctorate and a reputation.

“He came with the recommendation that counts: He’ll work,” recalls B.J. Copeland, then a researcher at North Carolina State University who had just taken the helm of the state’s fledgling Sea Grant program.

Hodson was willing to take a chance on the new setting, “I told B.J.: If you offer me the job, I’ll take it,” he says with a smile. Little did he realize that his new research associate position would grow into a career of service to North Carolina.

As Hodson prepares to retire as North Carolina Sea Grant Director on June 30, his work ethic and no-nonsense personality continue to draw praise and respect.

“What you see is what you get. There is no pretense,” says Jim Murray, former North Carolina Sea Grant extension director and currently acting deputy director at the National Sea Grant College Program.

”You know where he stands on a decision and the reason for it — even if you don’t agree. Then you can move on. You can trust him,” Murray says.

Jimmy Johnson has worked with Hodson on many levels — as a seafood processor, as chairman of the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission, and now a coordinator for the state’s Coastal Habitat Protection Plan.

“When I was in the seafood processing industry, the industry knew that Ron, and Sea Grant, was always there. If we had a need — some research work we needed help on — we knew we could go to Sea Grant, and something would happen,” Johnson explains.

Bob Hines, a veteran Sea Grant fisheries specialist, agrees. “Ron has a great ability to identify issues where Sea Grant can be of service,” he says.

And Hodson not only is in tune with the people and issues of North Carolina, but he also understands the coastal ecosystems. “In my mind, this melding of science and an innate understanding or ‘feeling’ for the natural world are a hallmark of Ron’s personality,” Hines adds.

Farmer’s Instincts

Growing up on a farm near Trotwood, Ohio, Hodson focused on school and chores, but made time to read historical and Western novels, and to explore outdoors.

Voted “Most Athletic” in his senior class of 1959, he went on to Wilmington College, southeast of Dayton, to play basketball.

After a ruptured Achilles tendon ended his basketball days, he moved to Manchester College in Indiana. He majored in physical education and biology, with plans to teach.

“About my junior year, I decided I didn’t want to teach in high school,” Hodson recalls.

Zoology professor Emerson Niswander encouraged him to go to graduate school. “He was the first person — other than my parents — to have shaped what I would do,” says Hodson, who headed to the University of Arkansas to study with ichthyologist Kirk Strawn.

His master’s thesis described the first-year life history of large-mouth bass in a new reservoir. He also collected “thousands and thousands of fish” from across Arkansas. “I knew all the fish on sight — I had a good eye for that,” he says.

“Getting a PhD seemed like a natural thing to do,” Hodson explains.

He started doctoral work at the University of Kansas, but soon headed to Texas A&M University, where Strawn had moved. “My farm background helped me be a natural in the field,” Hodson recalls.

By 1972, Hodson was almost finished with his doctorate. A friend offered him a job in Nicaragua to work with a fish company. Ron and his wife, Ruthie, his high school sweetheart, quickly joined in the adventure.

During a side trip to Costa Rica, a conversation with friends turned to the Hodsons’ long-held dream of adopting a child. The friend thought it was such a good idea, she immediately called the national orphanage, and offered some surprising news: A week-old boy needed a family.

The Hodsons and their friend headed to San Jose the next morning. After one long interview and a visit to the foster home, they started the paperwork, including gathering reference letters from friends.

“He was 15 days old when we picked him up,” Ron Hodson recalls. They named their son Todd.

In late 1972, the family returned to the U.S. for Ron to finish his dissertation — and prepare to enter the job market. One prospect was the research job with Copeland at NC State.

“When I thought of the East, I thought of Washington, D.C., and New York City,” Hodson recalls. But Copeland’s project — to quantify the thermal impacts of the new Brunswick Steam Electric plant — was right up Hodson’s alley. Field work would be in Brunswick County with lab analysis in Pamlico County.

The project grew, and Hodson would have a lead role in six years of field work. He came to Raleigh in 1979 to focus on final reports and journal articles.

“I was the big picture, and Ron was the scientific detail,” Copeland recalls. “We were a good team.”

Aquaculture Aptitude

By 1981, North Carolina had a Sea Grant College Program — and an opening for an associate director, Hodson applied.

Bill Queen of East Carolina University was on the search committee. “He had a question: Could I keep the Sea Grant aquaculture effort going in Aurora?” recalls Hodson.

About half of Hodson’s new position focused on research administration, and half on aquaculture. “He knew fish — and aquaculture was the coming thing. Sea Grant needed to be in it,” Copeland says.

Early on, Hodson set a goal of hybrid striped bass production for the seafood markets — building upon work started by Howard Kirby.

An initial mission was to build a hatchery. “By 1986, we knew we could do this on a commercial scale,” Hodson recalls of the work to culture the striped bass/white bass cross for food markets.

In 1987, Hodson received a $100,000 grant from the National Coastal Resources Research and Development Institute to transfer the research technology for pond aquaculture to a pilot commercial operation. But at the last minute, the original farmer pulled out.

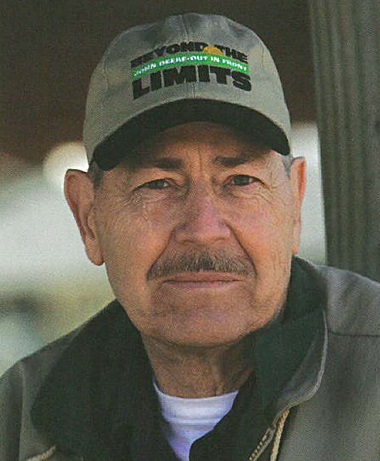

Colleague Randy Rouse suggested Hodson talk with father/son team Lee and Harvey Brothers in Beaufort County. “It was the beginning of a great relationship,” Hodson explains.

Lee Brothers agrees. “I consider Ron a true friend,” he says. “Ron is a phenomenal man. He’s got so much common sense along with his academic sense.”

And Hodson challenged him to stay focused on the goal — even if it meant going into a pond in February to sample fish. “If he was going in, I had to do it too,” Brothers adds with a laugh.

The first year, the team lost a lot of fish — but not their determination.

Lundie Spence, former North Carolina Sea Grant marine educator, recalls going to the farm one Saturday with Ron. A parasite was threatening thousands of baby bass. “Ron was with the family the whole time, sharing the stress, bringing in the experts and added support,” Spence explains.

By 1988, the team had the first demonstration crop —70,000 pounds of pond-raised hybrid striped bass for the food market.

The previous year, Jim Carlsburg, in a private venture in California, had the first commercial production of hybrids in tanks. The combined industry — including ponds mid tanks — took off, thanks in part to a moratorium on striped bass fishing in the Chesapeake region in light of declining natural stocks, along with new fishing limits in other states.

North Carolina proved to be ideal for pond aquaculture — with its clay-based soils and flat coastal plain. The Castle Hayne aquifer provided great quantity and quality of water for aquaculture, with especially good calcium levels.

The N.C. General Assembly recognized economic potential in coastal aquaculture, and appropriated $400,000 for NC State to hire researchers and extension staff.

The group included researcher Craig Sullivan, who joined NC State to focus on the reproductive physiology, and later genetics. Hodson, Sullivan and others worked with the Brothers at Carolina Fisheries, and with other new fish farmers.

“Ron provided great service to these ‘green’ farmers,” Sullivan says. “He took them under his wing, and worked boot-to-boot to teach them about critical factors — spawning, grading, and dealing with parasites, pathogens and water quality management.”

At one point, the state had more than 20 hybrid striped bass farms. Today, 19 are still operating. About 3 million pounds are produced here annually — a quarter of the 12 million pounds produced nationally.

A founding member of the Striped Bass Growers Association, Hodson helped write the bylaws and served as president, secretary and on the board of directors. He continues to serve as the “special scientific advisor” to a national breeding program to develop a domesticated broodstock.

“In my view, Ron Hodson is the father of the pond-reared hybrid striped bass,” Sullivan says. “It was a visionary undertaking on his part.”

Copeland agrees. “From research to big business — it is a world-famous accomplishment.”

A Lesson in Leadership

In 1997, Hodson was named interim director for North Carolina Sea Grant, and in 1998 became full director.

Less than a year later, his life would change dramatically.

After a national aquaculture meeting in Florida in January 1999, he and Ruthie were visiting friends. A flight in the friend’s small plane ended in a tragic crash. Ruthie and the pilot’s wife died from extensive injuries. Ron and the pilot would spend weeks in hospitals and months in physical therapy.

Despite physical pain and emotional trauma. Hodson found strength in family, friends and his work.

“I never once heard him complain about his situation. I only saw his determination to continue to live life to its fullest,” says Johnson, who often seeks out Hodson’s table at banquets and meetings. “We love listening to him talk and listening to the passion he has for Sea Grant and coastal North Carolina.”

Hodson now uses canes to walk short distances and a wheelchair to maneuver along longer routes — and as a comfortable seat for long meetings. The accident also changed his management style. “I had to learn to delegate more,” he says with a smile.

In his nine years at the helm of North Carolina Sea Grant, Hodson says he has seen the program’s “buying power” decrease in light of rising costs. “We must change the way we do business. We will be looking for additional sources of funding,” he says.

While they have different personalities and styles, Hodson says that he continues to use lessons he learned from Copeland. “B.J. showed the strength of a diverse program based on needs identified by stakeholders.”

During his tenure, Hodson says he has strengthened the review process for research proposals. And many Sea Grant projects are multidisciplinary in order to provide the best science on pressing coastal topics, he adds.

“We’ve always had a great staff: extension, communications and administrative,” Hodson says.

Many new outreach staff members are arriving with advanced degrees — a sign of the times. “They’re not teaching folks how to catch fish better. We are helping people deal with regulations and manage coastal resources,” Hodson says.

Sea Grant also has administered the state’s Fishery Resource Grant Program (FRG) since 1997. “Every year, the quality of the proposals improves,” Hodson says. “This was our strongest year yet.”

The FRG program, along with the Blue Crab Research Program also funded by the state, strives to pair researchers with academics. Rather than ”butting heads,” the two groups often now partner to test theories based on local knowledge of fisheries and ecosystems.

“If we are going to solve some of these management questions, they are going to have to work together,” he says.

Hodson has provided leadership to the national Sea Grant network as well, including serving on the board of the Sea Grant Association and as the directors’ liaison to the Assembly of Sea Grant Extension Program Leaders.

New Plans

A few years after the plane crash, Hodson was ready to start thinking about dating — a daunting task for someone who had been married for 36 years. He tried a modern tactic, online dating services, with varying success.

But it was an old-fashioned introduction by friend Joan Messina, a former Sea Grant But it was an old-fashioned introduction by friend Joan Messina, a former Sea Grant employee, along with encouragement from Todd, that led Ron to ask Kay to dinner.

What was her response? She wondered what took him so long.

They were married within a year. She brought two married daughters to the family, and Todd married the next year.

Family — which now includes five grandchildren — will play a leading role in Hodson’s “so-called” retirement.

And a new van will get mileage as he and Kay plan some travels, especially during winter months.

Hodson also plans to stay active professionally, with an emeritus role in NC State’s zoology department and an interest in new marine aquaculture opportunities. Folks are already asking him to serve on state and national committees.

He also will make time for personal projects, albeit with the family flair. He plans an expanded garden on his 20 acres near Apex, to provide fresh vegetables for his table and others.

And he may even raise a ”heritage breed” of chicken known as Buckeyes. Not a bad plan for a farm kid from Ohio.

This article was published in the Early Summer 2006 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: