SEA SCIENCE: Aquatic Science Within Reach: Fisheries Research Provides Classroom Lessons

The three-decade decline of American shad, river herring and blueback herring fisheries in North Carolina and other Atlantic states is more than a research topic for a team at East Carolina University.

It’s also the foundation of classroom activities and outdoor experiences for middle and high school students to learn more about coastal waters.

As part of research funded by North Carolina Sea Grant, biologist Anthony Overton and science educator Rhea Miles are fine-tuning lesson plans and products field tested with students in a science camp. Activities include self-guided projects that aim to increase competence in science, to motivate students to pursue scientific careers and to make science more relevant in everyday life.

At first, some students were hesitant to jump in. “But once they got their feet wet, their interest grew and they enjoyed learning more about aquatic life,” Overton explains.

The classroom materials are aligned with national science standards and North Carolina’s competency goals. By making materials and lectures accessible and user-friendly, the researchers hope teachers across the state will adopt the lesson plans to expand their curriculum while sparking student interest in aquatic sciences.

The teaching modules will be available as free downloads through a Web site, and will be distributed through the ECU Center for Science, Mathematics and Technology Education.

“When creating lesson plans, you have to be mindful of a teacher’s budget,” Miles notes.

Overton, Miles and their graduate students already have shared science activities with more than 50 students, teachers and others in the past two years. The outreach includes an exhibit at the 2008 and 2009 Grifton Shad Festival. The team also offered tours of the ECU Experimental Fish Laboratory in May 2008 to show Pitt County 4-H members methods used to raise American shad larvae, which is part of the Sea Grant research project.

The most intensive lessons — for youngsters and the research team — came in a July 2009 camp at ECU. Twenty-four youngsters from Pitt County middle schools participated in the Reach Up Summer Scholarship program for African-American students, funded by the GlaxoSmithKline Foundation’s Ribbon of Hope Program.

For three weeks, students focused on aquatic and environmental sciences, engaging in daily activities and lectures related to biology, geology and chemistry.

REACHING UP

“Listen up class. Today’s lesson is ‘What are Zooplankton,’ ” announces Samantha Binion, biology graduate student and research assistant for the Sea Grant project. Students immediately open their notebooks, ready for the session.

Binion and Becky Deehr, a doctoral student in coastal resources management, energetically explain how the sharp spine of a species of zooplankton also protects it from predators by increasing its surface area to make it appear larger.

“Okay class, here are two fancy terms you can impress your parents and friends with: ‘holoplankton’ and ‘meroplankton,’ ” Deehr says. Holoplankton are organisms that remain plankton for their entire life cycle, while meroplankton are only zooplankton for part of their lives. Some fish, including shad, along with snails, crabs and polycheates, go through a meroplankton stage.

The youngsters excitedly scribble notes onto paper.

After the introduction, Deehr and Binion move into a zooplankton identification game. “What’s this one,” Deehr asks as a picture pops up on the screen.

“A cocoa puff,” shouts one of the students.

“Close,” Deehr replies with a grin. “It’s a copepod.”

Next up are photos of a porcelain crab in its first stage of life and at maturity.

“How can it look like that — and grow into that?” one student asks.

“It’s like a Pokemon,” another student observes, citing popular cartoon characters.

The lesson taught by Deehr and Binion was adapted from the module “Life near the Surface,” intended for grades 6 to 8.

Reach Up participants were the first to meet the team’s detailed objectives: identify and describe important organisms which comprise phytoplankton and zooplankton; demonstrate an understanding of the most important adaptations of epipelagic organisms — those living among the sunlit layer of the ocean — and summarize examples of these adaptations; explain the most important characteristics of

epipelagic food webs; and demonstrate an understanding of the basic geographic and seasonal patterns of primary productivity, including the effects of upwelling.

“Most of the students did not have a clue about plankton, and their role in food webs,” Overton says. “But once we engaged the students through discovery, their appreciation and understanding of the aquatic environment blossomed.”

The 10-page module includes background information, a list of materials, procedures, suggested readings, Web links, exercises and vocabulary, as well as crossword and word search puzzles.

The team will meet with teachers to get additional input. And the researchers will work with teachers who want help using the lesson plans.

AN AMAZING RACE

The most challenging part of the module is the zooplankton “race” because it requires the most materials.

Students clear their desks to prepare for a race where the slowest finisher is the winner. The lesson highlights the need for zooplankton to float high in the water column, close to their food.

“Off to the Races” takes 35 to 45 minutes and gives students a chance to create their own zooplankton creatures. Each day model — which can include straws, toothpicks and feathers — will be timed as it descends in a 36-inch clear cylinder filled with water.

“The race times have changed weekly because we’ve added new materials,” Binion says. “The toothpicks and feathers add seconds to the students’ times.”

Students take different approaches to creating their zooplankton. Some focus on constructing a beautiful creature using brightly colored toothpicks and feathers, while others are more strategic, gauging which materials would work best.

Overton demonstrates, with a time of 8.47 seconds. In the students’ first attempts, most clay creatures sink instantly. After a few practice runs, times improve as students identify features that allow zooplankton to glide slowly through water.

“That was the best model I’ve created in the five years I’ve been doing this activity — trust me,” Overton says.

MORE MODULES

With “Life near the Surface” a success for the Reach Up program, Overton is working with Miles to test additional modules.

“The educational portion has been a challenge because as scientists, we are not often asked to extend outside the scientific realm,” Overton notes. “But I’ve enjoyed it.”

ECU graduate students Kenneth Riley and Kelly Riley have assisted Overton with the “Stream to Sea: Fish Populations” lesson. Kelly, a teacher at Oakwood School in Greenville, successfully tested the module with her students. Kenneth worked on the curriculum design.

“Ken 1s very visual, which is necessary when designing academic pages for younger students,” Overton says.

Intended for middle and high school students, the module incorporates biology and mathematics. Students learn how fishery scientists estimate different populations of fish within a community — a familiar task for Overton and his graduate students.

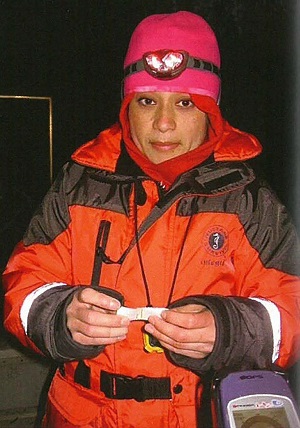

Binion collected zooplankton weekly from March to June 2008, and again in 2009 as part of Overton’s Sea Grant research that looks at food availability and nursery habitat in the success of shad and herring restoration efforts.

The exact reasons for the species decline are unknown, but scientists suggest that overfishing, decreases in water quality and loss of habitat are likely causes. “I’ve been able to take what I’ve learned in the field and apply it in the classroom,” she explains.

The “How Many Fish are in the Stream” activity demonstrates how researchers use “mark and recapture” methods to estimate size of fish populations in bodies of water.

Teachers need three types of fish — or in this case, multi-colored beans or Goldfish crackers — along with a paper bag, a permanent marker, plastic bags, laboratory sheets and a plastic bag.

The activity, which lasts about 80 minutes, meets national science standards. The module includes discussion questions and additional activities.

In order to enhance coastal ocean literacy among students, skilled teachers need a rich array of learning materials, Overton and Miles note. The field-testing not only has explained general concepts, but also has given teachers opportunities to discuss scientific research in nearby waters.

“By making these materials available on line and through East Carolina University, teachers now have ample opportunities to teach Pitt County students about what’s in their own backyard,” Overton says.

For more information, contact Anthony Overton at 252-328-4121 or overtona@ecu.edu. Or go online to .

ESSENTIAL HABITATS FOR HERRING, SHAD

What ecological processes influence the movement of young herring to the Albemarle Sound?

Anthony Overton, a biologist at East Carolina University, is looking at larval fish distribution, as well as levels of zooplankton — food for the fish — from the lower Roanoke River to Albemarle Sound.

The goal is a better understanding of “essential fish habitat” in the region — a focus of state and federal efforts for ecosystem-based fisheries management for Amencan shad (Alosa sapidissima), river herring (A. pseudoharengus, also known as alewife) and blueback herring (A. aestivalis).

Funded by North Carolina Sea Grant, the sampling 1s done during peak periods of larval herring production from March to July. Initial analysis indicates that the delta Is the most important area for the herring development. Mean abundance of herring larvae in the delta is almost twice as high as abundance in the river areas, and 4.5 times higher than in the sound areas.

The zooplankton sampling is still under review. But early analysis shows that the diversity and abundance of zooplankton prey for larval river herring is higher in the sound area — where the larval herring levels were lowest. Overton’s team will continue to assess differential growth, and natural mortality in the region.

The researchers also want to determine the combined effects of temperature and prey levels on survival and growth of American shad larvae.

“Recent surveys in North Carolina suggest that stocks are continuing to decline despite extensive management and stock enhancement efforts,” Overton reports.

This article was published in the Holiday 2009 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: