ON CURRITUCK POND: A New Project Teaches About Stormwater Pollution and Coastal Health

Mainland Currituck County is experiencing a gentle reawakening. The sleepy, humid coastal air that bathes this serene lowland of hardworking farmers and fishermen and buoys many an easygoing Sunday afternoon is now joined by a steady breeze of innovation and inspiration.

A site for this reawakening is the Currituck County Cooperative Extension center. Staff members there are working with residents, county partners and local businesses to better utilize and preserve the land and waters they depend on, while balancing the demands of economic growth and historic livelihoods.

A hub of education and collaboration, the center is within a mostly undeveloped 95-acre tract. Central Elementary School sits next door, and the county plans for the campus include a senior center, a YMCA and athletic fields — the foundation for a vibrant community center for all of Currituck County.

Previously, a barren stormwater collection pond with unflattering algae welcomed visitors driving into the campus. But in recent months, a rebirth has been taking place. With the help of North Carolina Sea Grant specialists, many partners are transforming this pond by adding a demonstration wetland to educate visitors on the intricate connections between coastal land use and inshore water health.

Like the campus and the county, this pond is finding new life.

MUDDY WATERS

When Gloria Putnam first drove up to the then-new Currituck Cooperative Extension center for a meeting in July 2008, she saw a huge, unshaded, denuded pond smack dab next to the main driveway. The lonely spout of an aeration fountain looked stark against the watery field. It gave her pause.

That pond looked out of place, says Putnam, water quality planning specialist at North Carolina Sea Grant. And Putnam was right-she was looking at a stormwater pond that was not meeting its full potential.

The stormwater pond was intended to collect rainwater runoff from the center’s parking lot and surrounding lawns, water that could carry oil, debris and nutrients into critical nearby sound waters if left uncontrolled To be most effective in stormwater treatment, a pond should incorporate vegetation — including wetland plants strategically placed at different depths, forming a gradually terraced filtration system.

With some updates, Putnam thought, this particular pond could provide an opportunity for Currituck County government and Cooperative Extension to lead by example.

So Putnam, who grew up in neighboring Pasquotank County, approached then-Currituck Cooperative Extension Director Rodney Sawyer with an idea of transforming the pond.

He agreed. “Field demonstrations are an often-used tool of Cooperative Extension, and this one will be used for tours, educational exhibits and a teaching lab,” Sawyer says, noting that the site will showcase high-quality “best management practices.”

Putnam turned to North Carolina Sea Grant colleague Barbara Doll to design and construct working wetland features for the pond.

METAMORPHOSIS

There’s a lot of negative connotation with wetlands. Many people think they’re just snakes and mosquitoes.

“But a constructed wetland is not going to be like that if it’s done right,” says Doll, a licensed professional engineer and Sea Grant’s water quality specialist. She has ample experience restoring aquatic habitats to more natural states — most notably with the Rocky Branch waterway on the North Carolina State University campus, a project she has shepherded for over a decade. (See Coastwatch Spring 2010.)

Putnam and Doll, whose positions each have some funding support from the statewide N.C. Cooperative Extension program, began brainstorming.

“A properly designed wetland will provide natural habitat for dragonflies and frogs that’ll eat up the mosquitoes,” says Doll. “And all the wetland plants will help trap pollutants before the runoff reaches the sound. It’s gonna be all good.”

Implementing such a design requires a properly assembled team. With funding from the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Program (APNEP) and Currituck County, Doll and Putnam gathered with county partners in the spring of 2010. By then, the project had another key element: a demonstration “wildlife garden” to show visitors native plants that will attract birds, butterflies and bees to their backyard.

“APNEP is pleased to partner with North Carolina Sea Grant in support of the Currituck Goes Green Initiative. This project will create an environmental education demonstration site that incorporates natural landscape features and native plants at a prominent county-owned location that allows it to demonstrate beneficial landscaping and stormwater control in order to protect the water quality in Currituck Sound,” says Bill Crowell, APNEP director.

Progress had to be made quickly — for the pond’s new wetland to be successful, the first plantings of vegetation had to take place by July in order to take advantage of the remaining growing season. That meant design plans, construction bids and suppliers had to be solicited and finalized within two short months, with another two needed for dredging, construction and planting.

Yet the restoration team came together ably. Georgia Kight came aboard as the interim director for Currituck Cooperative Extension. County Engineer Eric Weatherly helped organize the bid process, while County Manager Dan Scanlon and planners Ben Woody and Holly White advised the plans and ushered the overall process forward.

“The importance of this project to me is a shifting in the understanding and function of storm water infrastructure,” says Scanlon. He helped Putnam and others to host a growth strategies training session at the center in May, with local officials from across the region seeing the pond and learning about plans for the site.

“If the ponds are not maintained over time and the system works marginally, then the community doesn’t understand their purpose and they become liabilities and eyesores. So there is an education opportunity with our project.”

Of course, when your project takes place on a county campus, expert opinion is a stone’s throw away. Mike Doxey, the Currituck Soil and Water Conservation District technician, took charge of construction oversight. Tommy Grandy, a Cooperative Extension agricultural agent, assessed the soil quality for plantings.

At center stage, of course, are the new aquatic plants that will act as the buffers and filters for runoff, along with the native perennials and grasses that encircle the pond. Ellen Colodney, owner of the Coastal Plain Conservation Nursery in Edenton, offered advice and options on native wetland species.

Right cites the “privilege” to have such a diverse team of staff and contractors from within Currituck County and beyond. “I was excited to be a part of the team and am proud of our accomplishments.”

TAKING FLIGHT

From her experience. Doll confesses that some of the more established municipalities in the state are more hesitant to implement new environmental projects. But Doll says working with the Currituck County staff” has been “very refreshing,” as she has enjoyed her collaborators’ open-minded attitude.

“It’s never a flat ‘No.’ Even if there are some barriers, the attitude is always ‘we can get this figured out.'”

Indeed, Currituck County is among the coastal counties that have taken initiative to usher in planning policies and educational efforts that sustain both environment — and people-sensitive practices. In 2009. North Carolina Sea Grant worked with Sawyer. Scanlon and other partners to initiate “Currituck Goes Green” efforts on sustainable development. (See Coastwatch Winter 2010.)

“We have an excellent, professional county staff,” Kight says. “They are knowledgeable and willing to work together to ensure that Currituck County is a premier ‘green county’ and have been very supportive of the Currituck Goes Green collaborative.”

Government approval is great, but local approval matters even more for this educational project. Doll isn’t worried. Having grown up on Currituck County’s Knotts Island, Doll knows that coastal people care strongly about their waters.

‘They’ve seen all the changes in the Currituck and Albemarle sounds all these decades.” Doll says. “They’ve seen the seagrass beds and the black bass – and they’ve seen them disappear with the change in water quality.”

And for the newcomers and the youth of the county, educational signs at the pond will explain how lawn and parking lot runoff can enter local waterways and impact coastal environments and fisheries.

Meanwhile, a North Carolina Sea Grant minigrant to the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute and NC State’s Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering is helping to monitor the wetland’s water quality during dry and storm seasons. Researchers will compare data before, during and after construction in order to gauge the project’s success.

REBORN

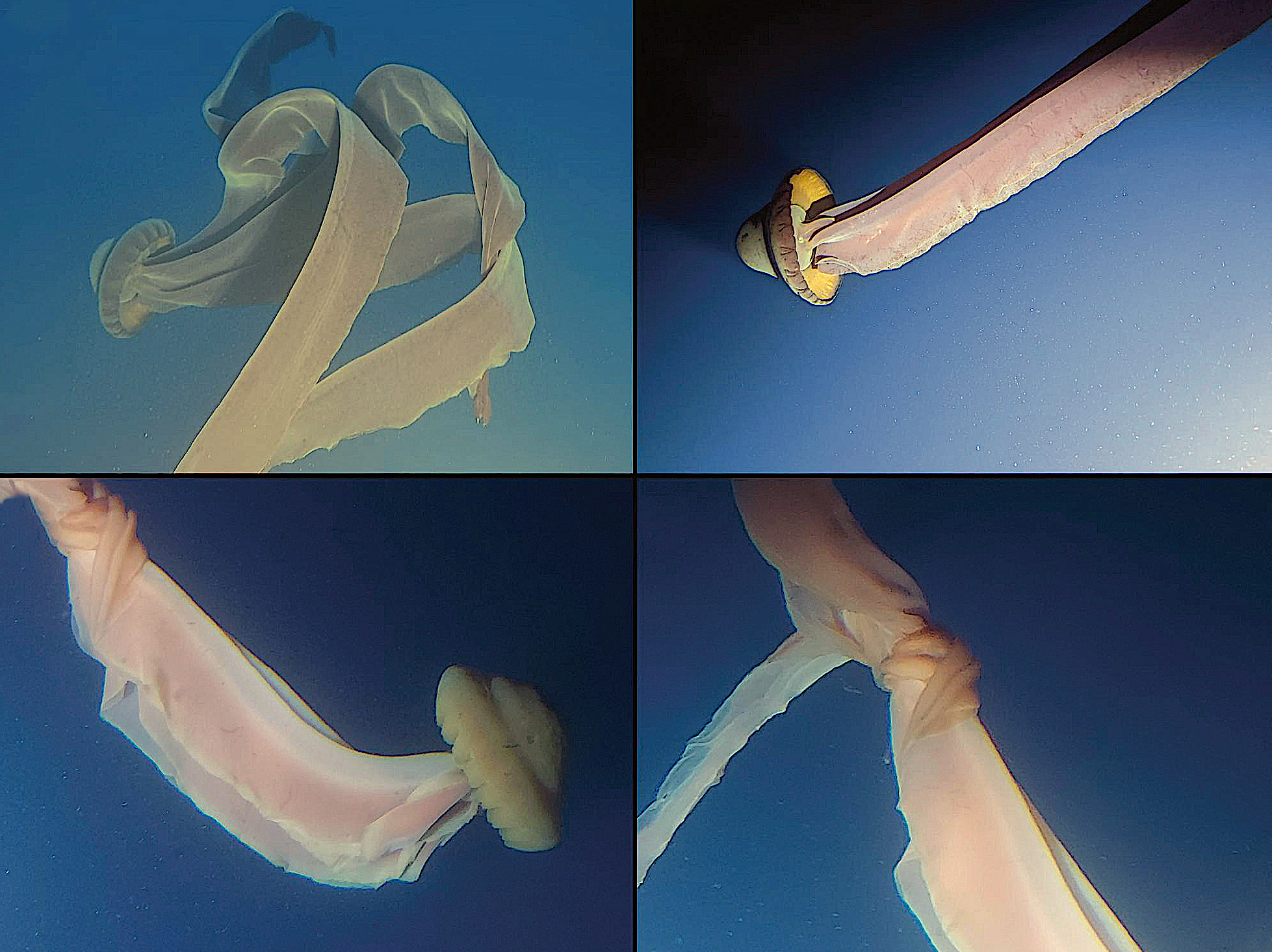

By autumn, the once-desolate pond is looking much more verdant and whole. Tall reeds — softstem bulrush (Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani) — follow the gently sloping bank into the water. They lead to long, wet terraces holding vegetation including fragrant waterlily (Nymphaea odorata) and lizardtail (Saururus cernuus). A splash can be heard as a spooked frog leaps off a frond and into the water.

The drive into the county campus is now more pleasing to the eye.

Off to the west of the pond is the wildlife garden, a splendorous array of native plants awaiting the coming spring and various visitors. Putnam collaborated with Jan Perry-Weber, Cooperative Extension horticultural technician, to plan the garden.

In October, before the first freeze, the pair organized a team of volunteer Currituck Master Gardeners and county staff for a morning of planting. “They were quite impressive,” Putnam says of the volunteers who were eager to work and learn. “We could not have done it without them.”

Now, beauty berry (Callicarpa americana), pink muhlygrass (Muhlenbergia capillaries). purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) and bee-balm (Monarda fistulosa) will attract wildlife with their nectar and fruits, and delight human visitors with their whimsical names and vibrant colors.

‘The wildlife garden will be another outside classroom that can be used for our master gardeners and landscapers, as well as students from our elementary, middle and high schools,” notes Kight, who recently retired.

The sentiment is shared by new Currituck Cooperative Extension Director Cameron Lowe, daughter of Rodney Sawyer.

“North Carolina Cooperative Extension partners with communities to deliver education and technology that enrich the lives, land and economy of North Carolinians,” Lowe explains. “The Currituck County center is committed to that mission,” she adds. “It’s our hope that we’ve established these projects as best management practices that will enrich the lives, land and economy of our county.”

The pond’s new wetland and nearby wildlife garden will need another few years to grow into their full potential, maturing with each passing season like the classes of school children who’ll visit over time.

As for Gloria Putnam and Barbara Doll, it’s another project all wrapped up. There are other barren stormwater control sites and abandoned creeks around the North Carolina coast still waiting for their chance to be reborn, waiting to be noticed by concerned citizens and local planners.

And Putnam and Doll will be willing and available to help.

This article was published in the Holiday 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: