North Carolina’s coast is a very sharky place. The fact that important shark habitat includes the state’s estuaries often surprises locals and visitors alike.

I’ve spent a lot of time with sharks in these waters. During graduate school at East Carolina University, I worked with the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries, or DMF, using their extensive fishery-independent survey data to study shark habitat within Pamlico Sound.

That work inspired a shark survey in Core and Back sounds that I conducted as a grad student, with support from a North Carolina Sea Grant minigrant. Now, as a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, or SERC, I’ve been surveying sharks in the lower Cape Fear River, with funding from North Carolina Aquariums.

So far, my surveys and DMF data have identified a dozen shark species in North Carolina estuaries. Many of those occur often enough to be considered regular members of these ecosystems. The murky waters conceal crucial feeding grounds for these predators, many of which are simply migrating through as they journey up and down the East Coast.

But some sharks grow up in these lagoons. For instance, young smooth dogfish show great affinity for seagrass beds on the sound side of the Outer Banks. Atlantic sharpnose sharks often give birth just inside the barrier island inlets.

My research suggests that lately, one species — the bull shark — has taken a particular liking to the protective nooks and crannies of the state’s largest estuary, the Pamlico Sound. Instead of meandering through the lagoon as they’ve done for decades, these sharks are giving birth there.

New Nursery Grounds

Bull sharks are well adapted to estuaries. These small-eyed, generally stocky sharks are among the few species that can tolerate low-salinity and even fresh water. For as long as people have been fishing in North Carolina estuaries, large bull sharks — they can grow upwards of 11 feet — have shown up on occasion. In contrast, juveniles apparently have been quite rare.

For example, in 2012, Frank Schwartz of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Science published an extensive study that combined DMF survey data, fishery landings and sightings to identify patterns of bull shark occurrence in N.C. waters. In a data set covering 1965 to 2011, he found records of only nine sharks within the juvenile size range for the species.

When I reviewed the DMF catch data for Pamlico Sound, I really didn’t expect to find many bull sharks.

But the survey years from 2007 to 2015 told a different story: Bull sharks were one of the six most common species in Pamlico Sound. What’s more, most of these sharks were less than four feet in length, which is well within the juvenile size range.

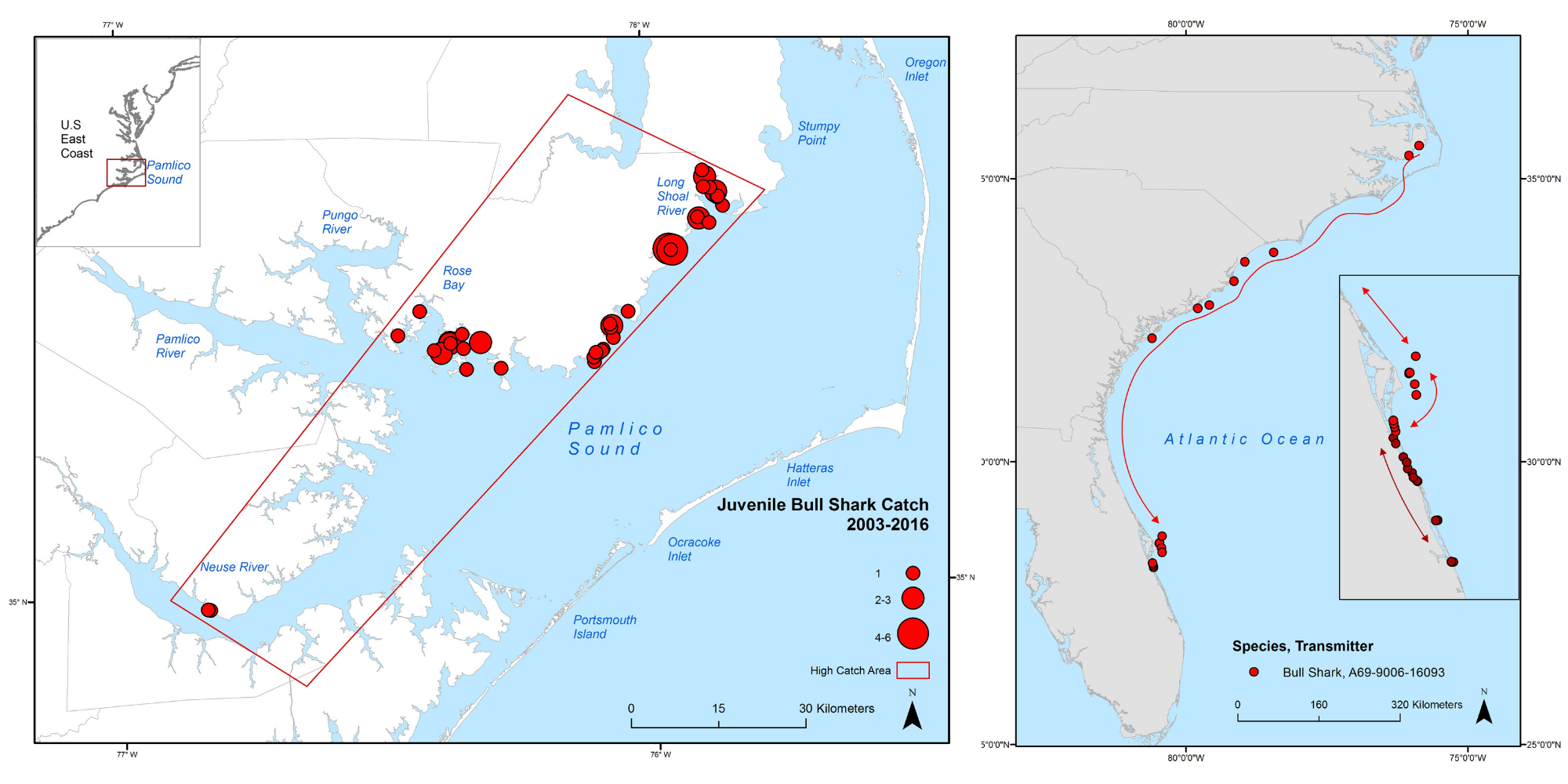

Many of them were near their size at birth — around two feet in length. Nearly all of them were captured in an area along the western side of Pamlico Sound, stretching from the Long Shoal River on the border of Hyde and Dare counties to Rose Bay near the mouth of the Pamlico River.

I used the survey catch data to map areas of likely shark habitat. As it turned out, bull shark habitat was predicted along the northwestern shoreline of Pamlico Sound. Habitat for every other shark species mapped closer to the inlets and barrier islands on the east side of the estuary.

The presence of small bull sharks in Pamlico Sound raised a question I hadn’t expected to ask: Is Pamlico Sound a bull shark nursery?

A 2007 paper by shark researcher Michelle Heupel, now at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, and colleagues identified three criteria for defining a shark nursery: Juveniles must be more common in an area than in nearby areas; they must spend an extended period of time in the area; and they are consistently found there over multiple years.

The catch data also showed that juvenile bull sharks are consistently found only in part of western Pamlico Sound from May to October every year since 2011. In other words, Pamlico Sound fit the definition of a bull shark nursery. The next question was why it had become one.

A Changing Estuary

With its limited ocean access and protected shallows, Pamlico Sound offers prime hideaways for juvenile sharks seeking refuge from larger predatory sharks accustomed to saltier ocean waters. Known bull shark nurseries south of North Carolina have similar features.

So why hadn’t bull sharks used Pamlico Sound as a nursery in the past? Its geographic features haven’t changed significantly. Another environmental feature must have shifted — and quickly — to make the estuary more inviting.

The DMF survey data and habitat mapping indicated that the juvenile bull sharks preferred warm water temperatures and brackish salinities. Data from the DMF gill net survey showed an increase in water temperature and salinity in the sound during the late spring and summer, going back to 2003. The estuarine trawl survey, which has been conducted since 1972, confirmed the temperature trend.

The most pronounced temperature increases occurred from May to July, corresponding with the time of year that bull sharks typically give birth in other estuaries. Salinity increases were less consistent year-to-year and appeared to influence the distribution of the sharks within the sound rather than their abundance.

In other words, temperature was the most likely explanation for increasing numbers of juvenile bull sharks in Pamlico Sound. Once temperatures in late spring and into the summer increased enough to consistently average greater than approximately 71°F, juvenile bull sharks began to appear.

These conditions are similar to those under which female bull sharks give birth in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, the species’ closest confirmed nursery habitat to Pamlico Sound. Put another way, temperatures in the sound had reached preferred levels for sharks to give birth.

The juvenile bull sharks of Pamlico Sound are a sign of a changing ecosystem.

Follow-Up Studies

Learning that Pamlico Sound has become a bull shark nursery raises a lot more questions. Where did the sharks — or their parents — come from? Do they remain in Pamlico Sound all year? What other species are they eating or otherwise interacting with?

In search of answers, I’ve returned to Pamlico Sound. With minigrant support from Sea Grant, I’ve been working since last summer with partners at ECU and DMF to study the family history of Pamlico Sound’s bull sharks.

We’re using two approaches: tracking and genetics. By tagging sharks in their core habitat area with acoustic transmitters, we’re gathering data on their movements. Through genetic sampling, we can compare their DNA with that of bull sharks in other areas to see if they’re related.

The process of tagging sharks goes something like this: We catch healthy sharks and bring them onto, or alongside, the boat. Then we roll them upside-down to induce an unconscious state called tonic immobility. While the sharks are in this unresponsive state we can perform our tagging procedures without fear of sudden movements.

We make a small incision in the shark’s underside and surgically implant an acoustic transmitter, then stitch the shark up and send it on its way. As the tagged shark travels, the tag transmits an ID code unique to that shark at a frequency higher than most animals can hear.

Those signals are detected and recorded on acoustic receivers deployed within Pamlico Sound and all along the coast. Not all of these receivers belong to us. We participate in research groups that use this technology, such as the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry and the Florida Atlantic Coast Telemetry networks.

Researchers in these networks who detect one of our tags can look up the ID number in a database of tagged animals and send us the data, and we do the same for them. In this manner, we can track our tagged sharks coastwide. Based on their location data, we can piece together their seasonal migrations.

We collect genetic samples from sharks by removing a small piece of the trailing edge of the dorsal fin. Working with geneticists at the Smithsonian and Texas A&M, we’ve been sequencing regions of the sharks’ mitochondrial DNA. Unlike DNA from the nucleus of the cell, mitochondrial DNA occurs in a part of an animal cell called the mitochondria. This DNA is generally passed to the next generation entirely from the mother.

We’re focusing on mitochondrial DNA because research on bull shark nurseries in Australia has found that pregnant females will return to the estuaries where they gave birth. As a result, there are genetic differences between shark populations that can be used to identify the nursery where a given shark was born.

Our genetic analysis eventually should tell us whether Pamlico Sound ‘s juvenile sharks are closely related to sharks from known nurseries in Florida waters or in the Gulf of Mexico — or if they’re members of a previously unknown population native to the estuary.

Our acoustic tracking and genetic sampling are starting to provide intriguing results.

So far, we have data on a single shark tagged in Pamlico Sound – a female likely within her first year of life. Tagged in early September 2017, she remained in Pamlico Sound until mid-October before leaving the estuary. Her tag signal was detected traveling along the South Carolina and northern Florida coasts until she reached Cape Canaveral, where she spent the winter.

This shark already has revealed some significant differences in movement behavior from what is currently known about juvenile bull sharks elsewhere. For instance, juveniles in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon remain within the estuary year-round until they’re nearly six feet in length.

That this tagged bull shark risked a long-distance trip through ocean waters inhabited by potential predators could signify a response to colder winters in Pamlico Sound. We’re still waiting to see whether she returns to the Pamlico Sound in the spring of 2019. If she does, it will suggest that Pamlico Sound provides enough beneficial habitat to make the long trip worthwhile.

As for our genetic analysis, we just finished sequencing some of the mitochondrial DNA from six sharks, including the one we’ve been tracking. Our next step is to make a detailed comparison with other bull shark nurseries.

Preliminary results indicate that there are two distinct genetic differences in the Pamlico sharks. One of those is represented by a single individual, so we still must confirm whether that genetic variation is widespread.

We’ll continue to monitor the movements of tagged sharks and to sequence genetic samples. We’re also investigating stomach contents and tissue samples to get an idea of what juvenile bull sharks might be feeding on.

Our findings will tell us a lot about the ecology of bull sharks in Pamlico Sound. They’ll also give us insight into how the estuary’s ecosystem is responding to larger-scale environmental shifts like climate change.

For more on sharks in North Carolina, click here.

Meet the Bull Shark

Carcharhinus leucas

Birth: 2-2.5 ft • Maturity: 6-6.5 ft • Maximum: 11.5-13 ft

Range and Habitat: Bull sharks are found worldwide in tropical nearshore and estuarine environments and are capable of entering and living in fresh water. The species gives birth in brackish areas of estuaries, where young sharks may live for the first 5 to 9 years of life. Both juvenile and adult bull sharks reside in fresh and brackish habitats in some areas, including Lake Nicaragua and some Australian rivers. Larger juveniles and adults also will migrate along entire coastlines and between nearshore waters and offshore reefs. Bull sharks have been found as far north in the Mississippi River as southern Illinois. The record distance upriver is held by a 6-foot shark captured in a tributary of the Amazon River in Iquitos, Peru. Bull sharks also will spend time within human altered habitats like canals, power plant outflows and marinas.

Diet: Bull sharks are apex predators in nearshore and estuarine environments, feeding on large prey including smaller bull sharks, stingrays, dolphins, and large fishes like tarpon and red drum. These sharks can exert an extremely strong bite force for their size, enabling them to take on prey nearly as large as themselves. Preliminary work investigating the stomach contents of juvenile bull sharks in Pamlico Sound also shows evidence of crabs. Fishing gear in the form of small hooks and sections of line also have turned up.

Behavior: Much of the social behavior of bull sharks is poorly known. Juveniles will form groups in nursery habitats. Larger bull sharks are usually solitary but will sometimes gather in significant numbers around productive feeding areas.—CB

This article was published in the Autumn 2018 issue of Coastwatch. For reprint requests, click here.