By JULIE LEIBACH

Divers can barely make out their hand in front of their faces at the Agnes E. Fry wreck site. Can you see the porthole?

Underwater archaeologist Greg Stratton knew he had reached the wreck site of the Agnes E. Fry, a Civil War-era blockade runner, when he scraped his hand against its iron hull during a reconnaissance dive in 2016.

“It just took all the skin off my knuckles,” says Stratton, who works for the North Carolina Office of State Archaeology. “I was like: Oh, there’s the vessel.”

The underwater conditions at the site are, in a word, terrible. The ship rests near Oak Island less than three miles from the Cape Fear River mouth, and less than a quarter-mile from the upwell pipes of a nuclear power plant. The pipes’ output “constantly churns the water,” Stratton says.

“It’s literally like diving in coffee, every time,” he says. “The five times I’ve been out there, my best day was a foot of visibility. Three of the times it was completely zero visibility.”

The Agnes E. Fry is one of about 5,000 wrecks thought to exist off North Carolina’s coast. Of those, the state has site files on nearly a thousand, according to Stratton.

Where Civil War wrecks are concerned, the Cape Fear area is a hotspot. Historical records show the waters off Brunswick, New Hanover and Pender counties contain 34 vessels — the highest density of Civil War-era ships in the world. Many have been added to the Cape Fear Civil War Shipwreck District, under the National Register of Historic Places. The majority are iron-hulled steamers like the Agnes E. Fry.

FOLLOWING A HUNCH

Archaeologists first located what they thought was the Agnes E. Fry on Feb. 27, 2016, after acting on a hunch.

Archaeologists first located what they thought was the Agnes E. Fry on Feb. 27, 2016, after acting on a hunch.

John W. “Billy Ray” Morris, deputy state archaeologist with a maritime focus, and fellow underwater archaeologist Gordon Watts had been conducting an updated survey of Civil War-era wrecks around the port of Wilmington as part of a National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program grant.

Shifts in sediment had exposed those sites to an extent Morris and Watts had never seen in their combined 80-plus years of experience. They wondered if the same sediment conditions might hold elsewhere in the vicinity.

“We knew there were three wrecks on the other side of the river — three blockade runners — that had never been found: the Agnes Fry, the Georgiana McCaw, and the Spunkie,” Morris says.

With their scheduled survey work done for the day, Morris and Watts decided to investigate. They motored toward Oak Island, following a path where they suspected the blockade runners to be.

Equipped with sonar and a magnetometer, which detects changes in Earth’s magnetic field, they searched for a signal. Astonishingly, they found one. “We both cracked up,” Morris recalls.

From their instruments readings, it was clear they’d found the remains of an ironhulled ship stretching more than 200 feet. “We were pretty sure we had Agnes Fry,” Morris says.

Since the wreck’s discovery, researchers have confirmed the identity, without a shred of doubt.

For the past two years, they’ve been intensively studying the vessel through remote sensing, reconnaissance diving and archival digging. The effort is part of a collaborative research project led by the state’s Underwater Archaeology Branch and the Institute for International Maritime Research, based in Washington, N.C.

North Carolina Sea Grant provided research funding, and the project team submitted its final report in April.

“This maritime heritage research was extremely interesting,” notes John Fear, deputy director of Sea Grant. “We were pleased that the results helped to identify this cultural resource as the Fry.”

WEAVING A TIMELINE

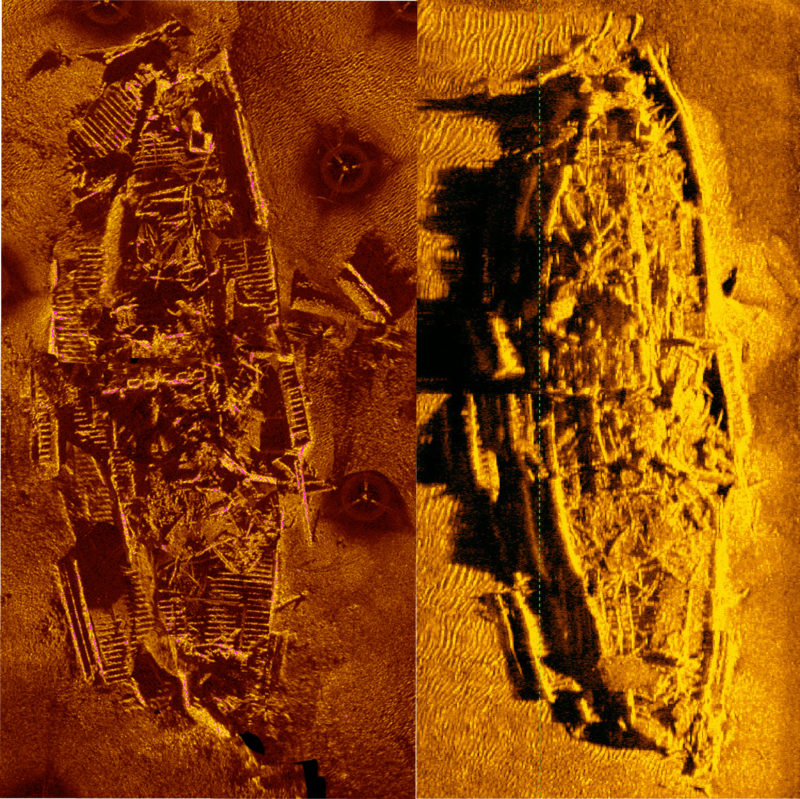

A comparison of images of the Agnes E. Fry created by sector-scan sonar, left, and side-scan sonar, right, reveals the precision of the former technique. Courtesy Nautilus Marine Group and DNCR

Scottish shipwrights originally built the vessel for a mail service company. The boat quickly changed hands when the Wilmington-based Crenshaw and Company purchased it for use as a blockade runner. During the Civil War, the Confederacy employed these stealthy steamers to sneak supplies past Union blockades and into Southern ports.

Historical records show that, after several attempts to break through a blockade of Wilmington, the Agnes E. Fry made one successful delivery in November 1864. On Dec. 27, the ship met its demise, running aground less than a month before Fort Fisher fell to Union forces.

Clues into the ship’s final moments came from an unexpected source: a diary belonging to one of its crew, Bernard Roux Harding. His great-granddaughter Mary Timberlake Parker had inherited Harding’s manuscript and sent an annotated version to the state’s underwater archaeology office shortly after it announced the wreck’s discovery.

“I’ve got an actual firsthand account of how the ship ran aground,” Morris says. Based on Harding’s notes, the Agnes E. Fry’s pilot had panicked at what he thought was an enemy vessel. Researchers now suspect that the pilot hadn’t spied a foe, but rather a sister blockade runner already run aground.

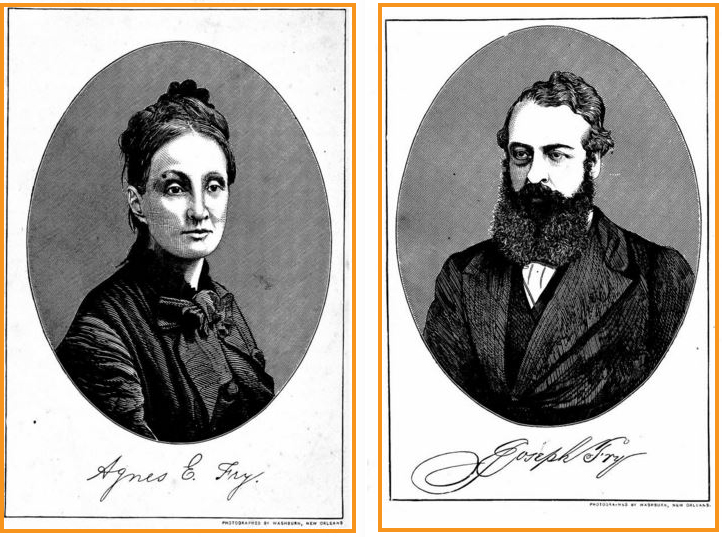

For his part, ship captain Joseph Fry survived the mishap, though he met his own fate nine years later. Cuban authorities caught him running munitions for insurrectionists during an uprising against Spanish occupation. Officials executed 53 crew members — including Fry. Though Americans clamored for war, the U.S. resolved the affair peacefully.

A U.S. naval vessel went to retrieve Fry’s ship — a former blockade runner called the Virginius. In a historical coincidence, it, too, ran aground near Wilmington.

“So, within 11 miles of each other, we have two blockade runners from two different wars built on the same river in Scotland commanded by the same captain,” Morris says.“Now how cool is that?”

GAINING PERSPECTIVE

Divers recovered a handmade knife handle from the Agnes E. Fry wreck. Courtesy DNCR

Divers also found a deck light, a low-tech device used to reflect light into dark crannies. Courtesy DNCR

Several years after the Agnes E. Fry struck bottom, the U.S. Navy extracted some of its machinery. Then in 1909, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers removed sections that obstructed navigation but salvaged nothing else.

The final official record of the ship — a 1920 report from the Oak Island Life Saving Station — describes the Agnes E. Fry’s general location. That the station didn’t mark its precise position on any charts is a “mystery,” Stratton says.

For the last century, the vessel has remained largely undisturbed, 18 feet underwater.

Despite the abysmal diving conditions at the site, archaeologists have managed to collect three artifacts, including a piece of coal, a deck light — a low-tech device designed to reflect light into dark places — and a handmade knife handle. “When you put it in your hand, you can actually feel the finger joints,” Stratton says.

The items were “just lying there inside the vessel, in the bottom sediment,” he adds.

For a clearer picture of the Agnes E. Fry’s current state, the project team used two types of sonar: side-scan sonar pulled by boat over a site, and sector-scan sonar. The latter is positioned in the water at different points around a site and scans in a 360-degree rotation.

The researchers recruited special ops divers from the Charlotte Fire Department Rescue Squad to position the sector-scan sonar, which was donated by Nautilus International Marine Group. Together sector scans form a composite called a mosaic, which is far more precise than the data collected from side-scan sonar.

The Agnes E. Fry looks good for its age. In fact, it’s one of the best-preserved blockade runner wrecks discovered to date.

“It’s amazing how intact it is,” Stratton says. What’s more, additional artifacts might be hiding within.

“Because the Agnes Fry ran aground right at the end of the war — right before the Union attacked and captured Fort Fisher — it was never unloaded,” Morris says. Given its superior state of preservation, “there’s a really good chance that her cargo is still on board.”

The project team is currently determining “the best methodological approach” to investigating the cargo holds, Morris says.

STEAMING AHEAD

Last year, the state named the Condor, another Civil War-era blockade runner, as its first heritage dive site. Sea Grant also supported research on that vessel, which sits near Fort Fisher, 25 feet underwater.

“The Condor is infinitely more diveable” than the Agnes E. Fry, Stratton says. “It’s amazing — they’re both about the same depth, about the same distance from shore, but one sits up here in front of the [Fort Fisher] museum, and the other sits down off the mouth of the river.”

While the public won’t be diving on the Agnes E. Fry any time soon, they might someday marvel at a 3D model. The project team also plans to nominate the vessel for listing in the Cape Fear Civil War Shipwreck District as part of an effort to add all the known vessels from that time period.

Despite the various challenges, documenting archaeological sites like the Agnes E. Fry is critical to preserving the state’s maritime heritage. A wreck is a “nonrenewable resource,” Stratton says. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”