The Long View

On June 14, Ben Cahoon, mayor of the Town of Nags Head on the Outer Banks, testified before a Congressional subcommittee in Washington, D.C. While the focus was offshore oil drilling, the discussion touched on climate change.

At one point, U.S. Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragán, from California, posed a question to Cahoon: “Is climate change something that you talk about in your city? Is this something that, when you guys talk about sea level rise, you guys make that connection?”

Although the query surprised Cahoon, he answered right away. “We’ve had a number of community forums, and we’ve had community discussion about the issue — what the potential impacts will be,” he replied.

In fact, climate adaptation is official business in Nags Head. In 2015, the town launched a new project called FOCUS Nags Head, an effort to overhaul its land use policies and ordinances. Last summer, the town completed the project’s first phase: a comprehensive plan that explicitly addresses climate change and sea level rise.

The new plan makes the town “the first in northeastern North Carolina to adopt some kind of policy on sea level rise,” says Jessica Whitehead, Sea Grant’s coastal communities hazards adaptation specialist.

Whitehead has witnessed first-hand Nags Head’s commitment to coastal resilience. For the past three years, she has been part of a collaborative team that has been engaging the community in conversations about the town’s unique vulnerabilities — and how to adapt to them.

“The residents of the Outer Banks are extremely resilient to coastal storms, but they will continue to be exposed to sea level rise and climate change in the future,” Whitehead says. “Sea Grant has extensive expertise at helping communities build on their resilience today and continue to adapt and improve that resilience for the future.”

Living on the Edge

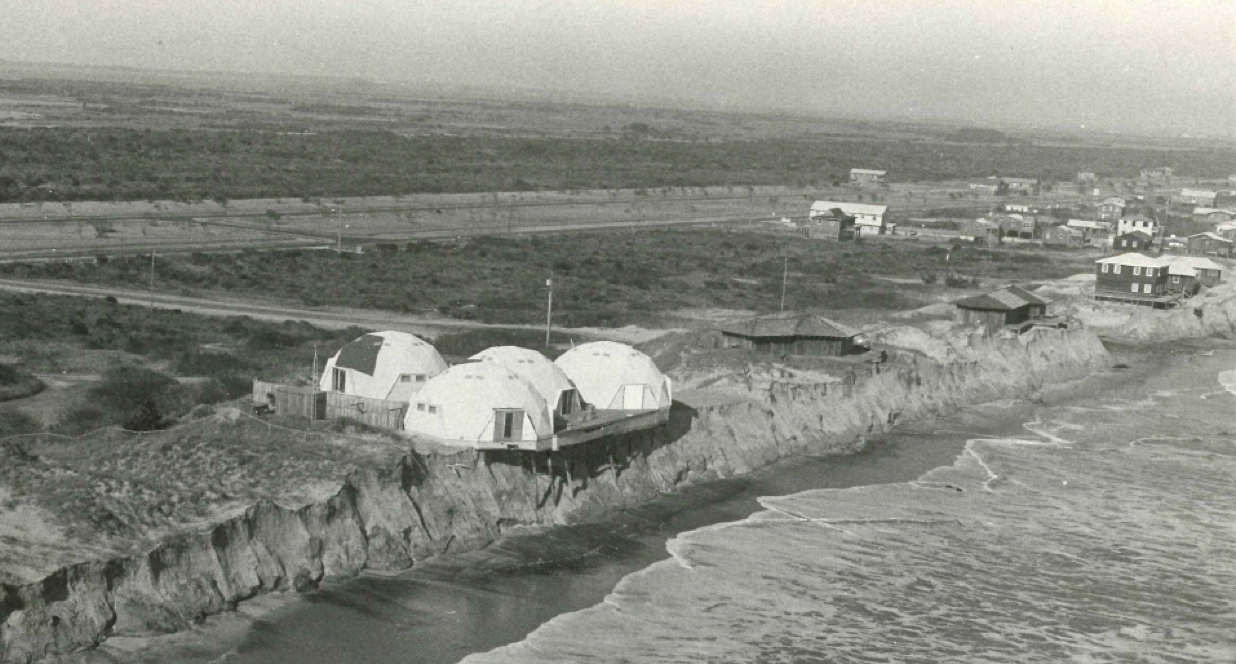

Since the 1750s, visitors have sought respite along the chain of barrier islands that form the Outer Banks. It wasn’t until 1838, however, that the region’s first public accommodations were built. With room for 200 guests, the Nags Head Hotel set the stage for a tourism boom that continues today.

Although Nags Head’s year-round population hovers around 3,000, its seasonal population can surge to 40,000 at summer’s peak. Welcoming visitors while preserving an intimate neighborhood vibe is a balance the town strives to maintain.

“I think Nags Head has always seen itself as a small-town beach community that prides itself in being a family vacation tourism location,” says Holly White, the town’s principal planner. “Of course, there’s always been an emphasis on and commitment to environmental conservation.”

Situated adjacent to the Cape Hatteras National Seashore in Dare County, Nags Head comprises more than 11 miles of ocean shoreline — the longest of any municipality in the county — and more than 45 miles of estuarine shoreline.

“It’s a very dynamic environment, one that can change continually,” says David Ryan, the town’s engineer.

Like other Outer Banks towns, one of Nags Head’s most alluring features — its proximity to sound and sea — also makes it vulnerable to coastal hazards, including tropical storms and nor’easters, inundation from storm surge,nuisance flooding, erosion and sea level rise.

The sea is rising across the entire coast of North Carolina, but the rate varies depending on location. For instance, geological data and measurements from tidal gauges indicate that the ground is naturally sinking along the Outer Banks faster than it is along the southern coast, according to a 2015 report prepared by the N.C. Coastal Resources Commission’s Science Panel. Subsidence alone substantially hastens the rate of sea level rise in northeastern communities like Nags Head compared to other parts of the state. A warming climate will likely accelerate that trend, Whitehead notes.

Nags Head officials also are concerned that storms with heavy rainfall are becoming more frequent. Intense rainfall events tax the town’s drainage infrastructure, which primarily relies on a series of discharge pipes that feed into the ocean and the sound.

Because a significant portion of Nags Head sits at or just above sea level, excess stormwater has little place to go. During periods of heavy rainfall, the town has experienced significant flooding — as much as three feet in some areas.

“If you’ve got water in your yard, you’ve got a nuisance. You’ve got water in your house, you’ve got a problem,” says Cliff Ogburn, Nags Head’s town manager. “I think we are recognizing an increase in problem flooding.”

Managing excess water is not just a matter of safety, but of health. Approximately 85 percent of Nags Head properties are on septic systems, which rely on sandy soils in the ground to filter out liquid waste. According to Ryan, when the ground becomes saturated with water — say, after a series of heavy rainfalls — that natural filtration process “has the potential to be short-circuited.”

Coming Together

Since the town was incorporated in 1961, Nags Head has had a strong tradition of policy and planning. In 1987, an article in the magazine Planning, published by the American Planning Association, noted that “Nags Head may be the planningest little town in North Carolina.”

What’s more, the article stated, “Nags Head has also set a standard for local planning along the North Carolina coast.”

The town already has been working to address problems that could be exacerbated by sea level rise. For instance, five years ago, a pilot project designed to provide drainage relief for a particularly low-lying neighborhood has since evolved into a permanent solution. The system relies on a series of pumps that draw in groundwater, channeling it to a higher elevation for discharge.

“I think we’re looking more and more toward pumped solutions in order to help improve the efficiency of lowering the groundwater and improving storage in the system that will have a net effect — not only on flood control, but also water quality over time,” Ryan says.

The town’s planning prowess was again evident in its decision to specifically address sea level rise in the FOCUS Nags Head project. “The fact that we’re even having this conversation — you know, we’re saying the words ‘sea level rise’ — I think it’s extremely progressive,” White says.

Town officials knew that outside expertise would be valuable as they developed a climate adaptation strategy. As White tells it, “it became very obvious that the ideal situation would be to run this process with Sea Grant.”

In summer 2015, Sea Grant began a collaborative extension project to provide Nags Head with scientific, policy and legal information to help the town better understand its vulnerabilities and plan for the future. NC State University, the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute, Carolinas Integrated Sciences and Assessments, or CISA, and Binghamton University in New York have provided additional assistance.

Involving the community was integral to the project. To that end, the team introduced to the town a participatory process designed to enhance public education and discourse about coastal resilience. Sea Grant’s Whitehead had co-created the methodology, known as VCAPS, for Vulnerability, Consequences, and Adaptation Planning Scenarios. (See below for more information on VCAPS.)

To start the process, the team first conducted a series of interviews in Nags Head with a sample of community stakeholders and decision makers. The idea was to gather a baseline read on how the town perceives sea level rise and challenges inherent to resilience.

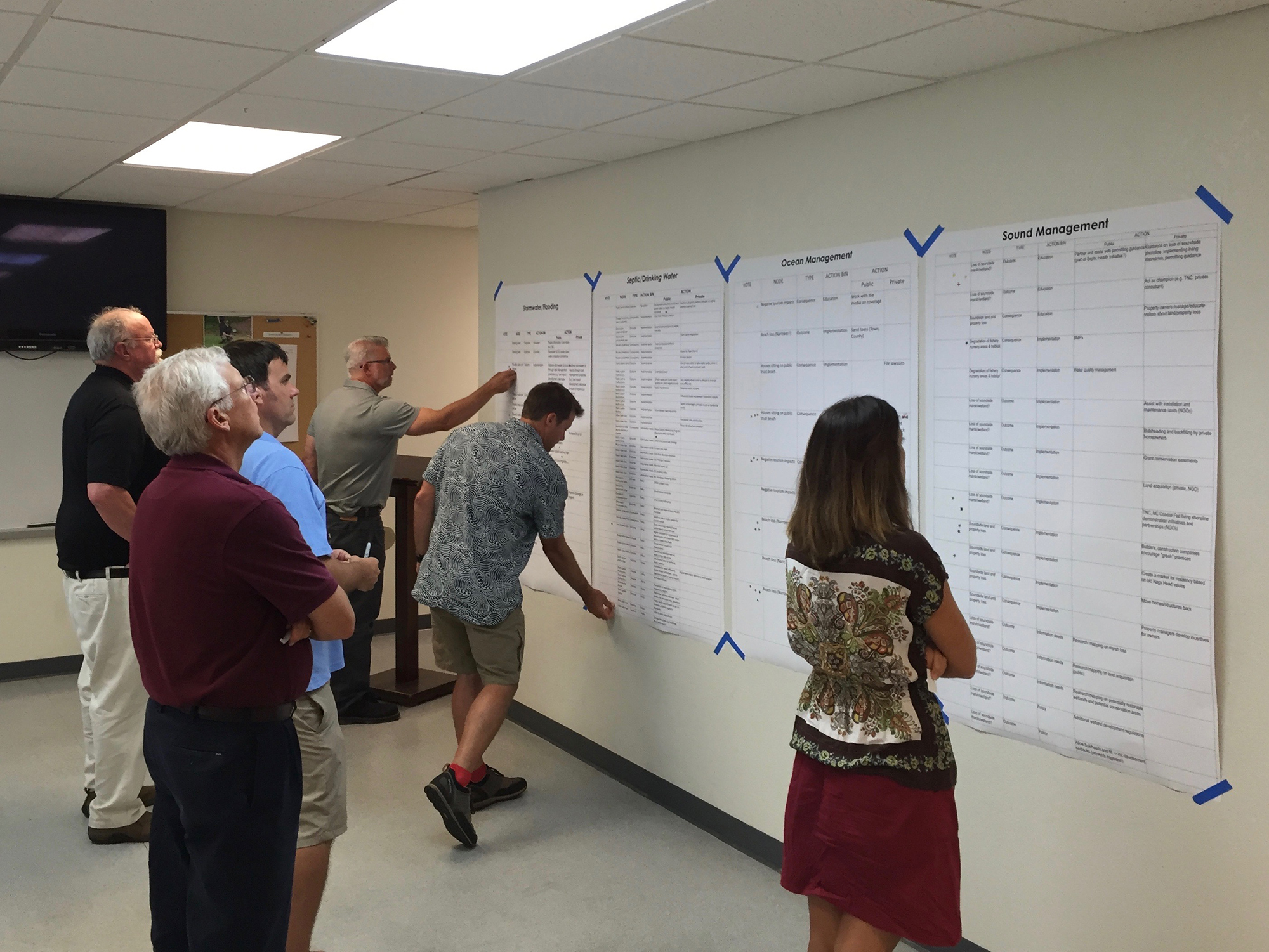

Information gleaned during those interviews guided the next phase: facilitated group discussions with community members, which took place over two days in late 2015.

More than 60 people attended, according to White. “It was a broad range of representation there,” she says, including real estate representatives, homeowners, business owners and academics, and even several curious residents from Hatteras.

The workshops gave participants the opportunity to ask questions, identify problems unique to their town, and brainstorm ways to address them.

“One of the things that we heard during the breakout group discussion is that the environment is their lifeblood because they’re a tourist town,” says California Sea Grant’s extension director, Lisa Schiavinato. She served as North Carolina Sea Grant’s law and policy specialist from 2007 to 2016 and was part of the project team. “They really care about having clean water, they really care that their roads are not flooded, they care about having healthy beaches, they care about having healthy wetlands.”

A critical component of the workshops was an exercise that helped participants identify actions the community could take to avoid or mitigate certain hazards. Participants poured themselves into the activity.

“We had a huge number of actions that had to be pared down and then prioritized,” White says. In fact, there were more than 150.

In 2016, Sea Grant guided a town subcommittee in pruning those actions. The team included the trimmed list in a final VCAPS report, which the town’s Board of Commissioners adopted in 2017.

The report is intended as a “road map” for Nags Head as it continues developing adaptation strategies, Sea Grant’s Whitehead says. Indeed, the town’s comprehensive plan incorporates several actions identified in the report, along with a scientific synthesis of sea level rise drafted by Whitehead.

For White, community participation has been essential to gaining public support for Nags Head’s planning efforts.

“When you begin to engage the community and you’re asking them, what do you think? Or, what’s important to you? Or, how do we accomplish this? Then it becomes really important for us to take the time to listen to what the community has to say and then figure out how to implement that, if possible. And all that takes a large amount of time,” White says.

“But the result is that you have a really thorough, comprehensive document, and you have a citizenry that’s extremely educated about the topics that they’ve been involved with. And as a result of that, they become champions of the plan.”

Facing the Future

Whitehead continues to work with Nags Head. When it comes to adaptation, the long view is key, she says. The time span of a typical 30-year mortgage won’t cut it.

“When you put in a stormwater pipe, it has to be there for longer than 30 years. When you put in a road, that road is in there, and you are stuck maintaining it as long as you can,” Whitehead says.

But improving resilience is, fundamentally, a learning process — one that takes time and patience. “Adaptation is a marathon, not a sprint. And in fact, it’s probably an ultramarathon,” she says.

As White sees it, Nags Head is already on the right track. “What I think I have learned through this process — of looking at how we adapt and become more resilient — is that there are a lot of things that we’re already doing,” she says.

“We’re already doing stormwater management planning. We’re already looking at beach renourishment. We’re already looking at hazard mitigation and how we respond. But we’re adding an extra layer, or lens, into these planning efforts.”

By weaving sea level rise into its policy and ordinances, Nags Head has set a precedent that could inspire others to follow suit.

“I would say to any town who came and said, ‘Hey, how do you do this?’ that it’s a longterm exercise,” says mayor Ben Cahoon. “You need to get started. Don’t wait on it. Go ahead and commit to it.”

Planning for Uncertainty

Adaptation is not a one-size-fits-all approach.

To improve their resilience to hazards, coastal communities must understand their specific vulnerabilities. One approach to helping decision-makers better prepare their towns for the future is a process called VCAPS, for Vulnerability, Consequences, and Adaptation Planning Scenarios.

Jessica Whitehead, Sea Grant’s coastal communities hazards adaptation specialist, co-developed the process in 2009, with partners from the Social and Environmental Research Institute (SERI) and Carolinas Integrated Sciences and Assessments (CISA), through funding from the NOAA Climate Program Office. At the time, Whitehead had a joint appointment as the regional climate extension specialist for the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium, North Carolina Sea Grant and CISA.

The VCAPS process hinges on engaging community members in open dialogue. The idea is that talking candidly builds an atmosphere of trust and understanding, which can lead to greater local support for adaptation strategies.

Those conversations are “the value-add of doing VCAPS,” says Whitehead, who’s also a member of the Independent Advisory Committee on Applied Climate, which is developing recommendations to help federal, state and local governments, communities and businesses plan for the effects of climate change.

The VCAPS process entails three phases. First, team leaders — such as Sea Grant extension specialists — interview local community stakeholders and decision-makers. Those interviews then guide the second phase, which unfolds over a series of facilitated group conversations open to the public.

As part of those discussions, facilitators lead a diagramming exercise that encourages participants to consider several categories: management concerns, such as public health; location-specific hazards, such as beach erosion; the effects of those hazards; and the implications of those effects. Participants also brainstorm ways to improve resilience.

In the third phase of VCAPS, team leaders create reports based on the discussions. Communities can then use those reports as guides for developing local adaptation plans, or for integrating new adaptation strategies into existing plans and processes.

So far, seven state Sea Grant programs have worked with academic and community partners and local jurisdictions to incorporate VCAPS into projects with 18 communities or industries. The Town of Swansboro is next on the list.

Click here for more information on VCAPS.

Managing Relationships

New planning processes that holistically consider water, wastewater and public health sectors are necessary to improve emergency response to coastal hazards.

Under the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium’s leadership, North Carolina Sea Grant helped develop a protocol designed to bring emergency managers, municipal planners, water and wastewater operators, and health officials together to consider the potential impacts of hurricanes as sea level rises. The goal is to identify where priority assistance is needed when planning for possible outcomes.

The team — which also includes researchers from East Carolina University, Old Dominion University and Virginia Tech University — tested the five-hour protocol during workshops in Charleston, S.C., and Morehead City, N.C., and has plans to create a guide for its use in other areas. For more information, contact Jessica Whitehead at j_whitehead@ncsu.edu.

This article was first published in the Summer 2018 issue of Coastwatch.

- Categories: