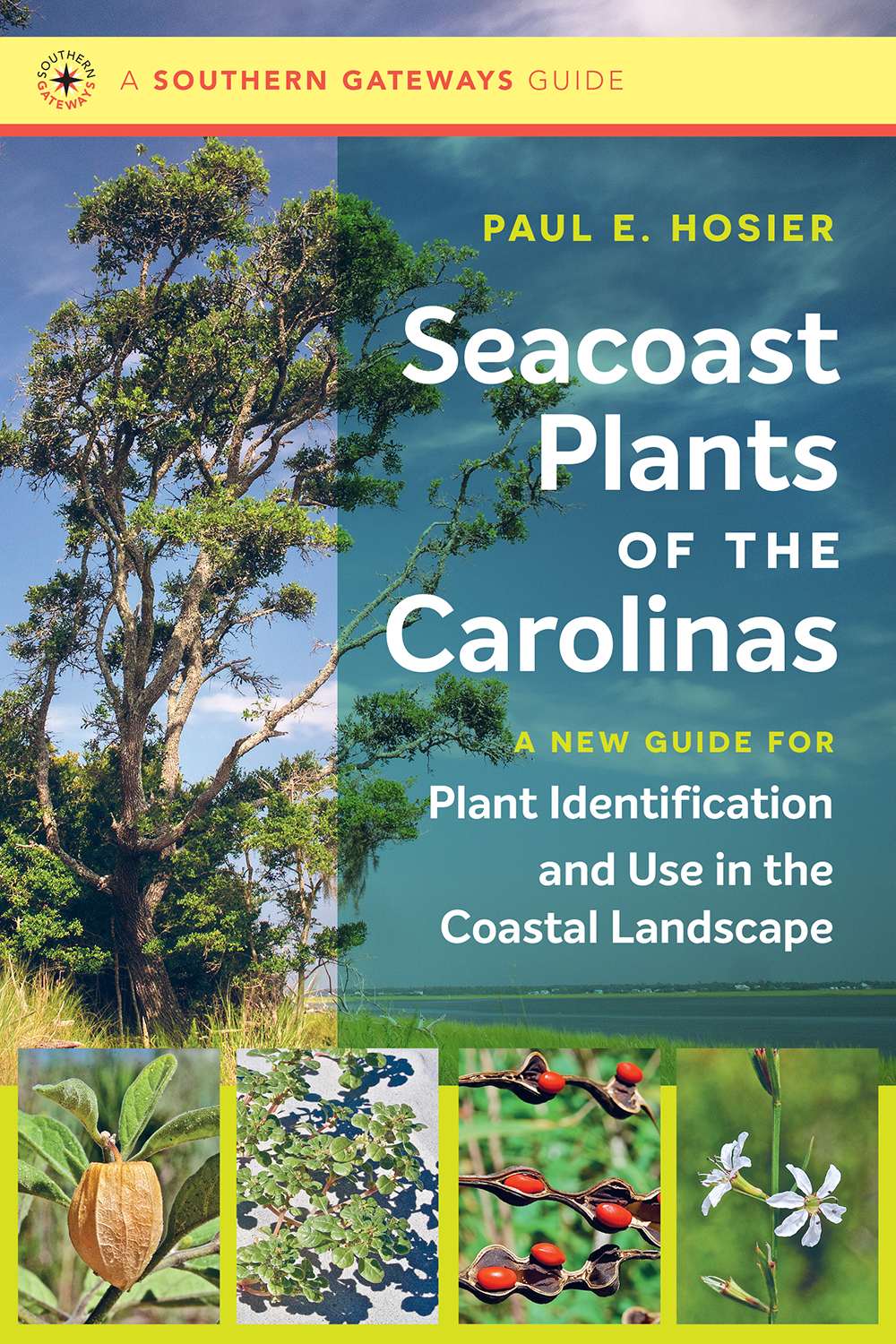

Thriving in Sun, Salt and Sand

Excerpts from Seacoast Plants of the Carolinas: A New Guide for Plant Identification and Use in the Coastal Landscape

Copyright © 2018 by North Carolina State University. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org

The coast of the Carolinas stretches from the unincorporated community of Carova Beach, N.C., located north of the Outer Banks, to Daufuskie Island, S.C., near the mouth of the Savannah River. Distinctive in many ways, the Carolinas’ coastal environment differs from the roller coaster-like Piedmont and the imposing Appalachian Mountains. A complex interplay of features gives the coast its identity. There are salty ocean waters and muddy estuaries, nutrient-poor and highly mobile sandy substrates, saltsheared forests and expansive coastal grasslands, occasional nor’easters and punishing hurricanes. These elements, combined with the dynamic wave and tide actions, merge in time and space to create a unique complex of conditions to which only a limited number of plants and animals have adapted.

The uncommonly attractive yet alien-appearing plant and animal communities created by the intersection of land, sea, and air draw many people to this coastal setting. Millions of people visit this region for action- or leisure-filled vacations each year; hundreds of thousands call the area home, and tens of thousands find fulfilling work there, ranging from commercial fishing to tourist-oriented service positions. This is all facilitated by — or because of — the existence of coastal communities and their natural surroundings.

While the Carolinas coast presents a somewhat varying geologic history and pattern of human land use, many environmental factors interact to create the distinctive setting that we sense and recognize as “the coast.” These include water (primarily salt water), sand, sun, wind, and storm activity. Here we find unique assemblages of plant and animal communities, including the beaches, dunes, forests, and wetlands. It is in these communities that we discover scores of plants, each exceptionally well adapted to the environment and coexisting with other plants and animals.

The Carolinas coastline varies from the long, narrow barrier islands of the Outer Banks anchored by Cape Hatteras to the high, wide iconic Sea Islands such as Kiawah and Hilton Head islands. Extensive dunes, maritime grasslands, and maritime shrub thickets dominate mile after mile of shoreline along the Outer Banks. In contrast, the topographically diverse and vegetationally complex islands of the southern North Carolina and the South Carolina coasts exhibit a preponderance of salt-aerosol-sheared arborescent vegetation, often with a narrow strip of grassy dunes along the seaward edge. Brackish marshes and salt marshes sharply define the edges of the upland communities along the estuarine shorelines of the Carolinas. Freshwater swamps, marshes, and ponds are embedded within the dunes and maritime forests.

Compared to the multifaceted and diverse dunes, grasslands, and forests, the marshes appear superficially similar. However, on closer inspection, we see that they range from structurally and vegetationally complex freshwater plant communities found in Currituck Sound to seemingly endless, monotonous expanses of estuarine marshes where but a single plant species dominates thousands of acres of intertidal environments in Port Royal and St. Helena sounds.

- Climate

Proximity to open water influences the climate along the Carolinas coast; large water bodies tend to moderate the climate by narrowing temperature extremes along the adjacent shores. This region experiences mild winters and hot, humid summers. Temperatures in the coastal Carolinas reach their average maxima of approximately 90°F in July and August and the minima in the mid-30°s F in January and February.

The Outer Banks of North Carolina report generally cooler average high temperatures during July and August (mid-80°s) and warmer average lows in the winter (high 30°s) than the rest of the coast. Because the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines its plant hardiness zones by the average minimum temperature experienced in an area, species adapted to higher minimum temperatures often thrive along a generally cooler coast. Conversely, species adapted to very hot temperatures rarely inhabit coastal plant communities.

Extraordinarily warm or cold temperatures experienced in the coastal Carolinas influence plants, since they have few thermoregulatory mechanisms compared with the animal world. However, plants adapt to at least short periods of heat and cold stress. Excessive heat during the summer leads to water deficits as water moves from roots to leaves and then to the atmosphere. This process desiccates plants and sometimes leads to the death of the plant.

Precipitation is abundant; however, summer droughts lasting for a month are not unusual in the coastal Carolinas. Annual precipitation in the region is evenly distributed throughout the year and averages 50 to 55 inches. The region experiences rainfall maxima in July and August; the least precipitation occurs in November and April. Rains accompanying hurricanes contribute significantly to summer rainfall totals.

The water table is usually close to the surface compared with more inland areas. Many trees and other deeply rooted plants can reach either the water table or the moist zone just above the water table. These deeply rooted plants can survive short periods of drought during the summer, a time when evapotranspiration lowers the water table. Similarly, deep taproots aid dune plants in collecting water during dry periods.

In extended drought conditions, coastal plants react by dropping leaves, which effectively reduces transpiration and therefore water loss. Deep taproots aid dune plants in collecting and storing water during dry periods.

- Tides and Salt Water

Tides are diurnal in the coastal Carolinas and increase in range from north to south. The spring tide range at the ocean edge varies from around 3 feet at Duck, N.C., to more than 7 feet at Hilton Head Island, S.C. In the estuaries, spring tides range from less than 1 foot in portions of Pamlico Sound to more than 9 feet in Port Royal Sound.

The presence of salt water is the most influential factor defining the coastal environment. Salt water is ubiquitous in the coastal zone; it is obviously dominant in the ocean and estuaries, but it is also important in the atmosphere in aerosolsized droplets. In addition, salt water may intrude into the groundwater when coastal aquifers experience excessive freshwater withdrawal. The tidally controlled ebb and flow of estuarine water defines and often delimits the environment in which saltwater-adapted plants live. Adaptation to the presence of salts in their environment is a unique and important attribute of coastal plants.

- Soils

Unconsolidated sands — geologically young with poorly developed soil profiles — comprise the soils of the coastal Carolinas. Much of the coastal plain of the Carolinas is composed of sands successively deposited in thin layers when sea level was considerably higher than it is today. Once the ocean retreated, wave and tidal action separated coarse sands from fine silts and clays. Over time, these processes created today’s estuaries, barrier islands, and barrier beaches. Today, winds move sand onshore, where native plants arrest this sand and form dunes. These sandy upland soils are typically coarse, dry, mobile, and nutrient deficient.

Moving water generated by the tides and river currents carries silt and clay into the low-energy estuaries typically found landward of the barrier islands in the coastal Carolinas. In sharp contrast to the dunes, tidal marsh soils are composed of silt and clay particles, and they are poorly aerated, often waterlogged, and frequently flooded with salt water. These markedly different environments support distinctive, easily recognized plant communities.

- Wind

Residents and visitors alike usually comment on the omnipresence of wind along the coast. The differential heating and cooling of ocean water and upland environments, as well as the low, flat nature of the coastal plain, creates conditions that generate and sustain nearly constant winds. The winds are important in shaping coastal environments; for thousands of years, wind and vegetation have interacted to form and reform the hummocky dunes and swales that characterize the Carolinas coast. Over time, winds move prodigious quantities of sand and subject coastal plants to burial of their stems or erosion of sand from around their roots. Winds are responsible for carrying salt aerosols shoreward, where they are deposited on the aerial portions of trees, shrubs, herbs, and grasses.

The coastal Carolinas experience winds from all directions in the course of a year; however, the strongest and most frequent winds blow predominantly from the northeast and southwest quadrants along the Carolinas coast. Variations occur depending on the location, season, and weather patterns.

- Salt Aerosoles

Rooted in place, plants cannot escape salt aerosols carried ashore by onshore winds flowing over breaking waves. Salt aerosols are intense near the beach, and only salt-tolerant plants survive here. Onshore winds deliver salt aerosols in large quantities to the highest dunes closest to the ocean, and aerosols decrease with increasing distance from the beach. In shallow, open estuaries where winds can generate breaking waves, salt aerosols can be carried considerable distances inland by brisk winds. Thus, plants growing near estuaries, sounds, and lagoons must tolerate atmospheric salts as well as elevated soil salinity. Many of the plants described in this guide grow along the estuarine shoreline.

Coastal Carolina native plants vary in response to salt aerosols. Most coastal species exhibit some tolerance. Plants occupying open dunes are well adapted to salt aerosols, while other species occupying, say, the maritime forest floor have no tolerance to elevated salts in the atmosphere — or in the forest soil for that matter. Injury is proportional to the concentration of salt aerosols reaching the plant. Near the ocean, atmospheric salt concentrations are high; at a distance from the ocean, atmospheric salt aerosols are nominal.

There are telltale symptoms of salt-aerosol damage: reduced stem growth, browning on the tips and margins of leaves, thinning of the leaf crown, premature leaf fall, earlier coloration of leaves, and death of twigs on the windward side of a tree or shrub. These symptoms often gradually appear in landscapes as salts build up on plant leaves and twigs or in the surrounding soil. When plants are exposed to chronic salt aerosols, expect to see crown dieback, insect and fungal invasion, and plant mortality. Salt aerosol damage is intensified when the coastal Carolinas experience drought conditions or low humidity for an extended time.

Selected plant profiles from Seacoast Plants of the Carolinas

Sea Rocket

Cakile harperi

- Family: Brassicaceae (Mustard)

- Other Common Names: Southeastern sea rocket, American sea rocket

- Range: Coastal: North Carolina south to Florida

- Habitat: Wrack lines, dunes, and maritime grasslands

- Flowing/Fruiting Period: FL &FR April- June

- Wetland Status: Facultative Upland Plant

- Origin: Native

A member of the nearly ubiquitous Mustard family, sea rocket is a conspicuous plant of the wrack-line and foredune habitat of the Carolinas coast. During any given year, beach scraping, beach grooming, storm overwash, erosion, off-road vehicle use, and development may erase the ephemeral wrack lines occupied by sea rocket; however, extirpation of this resilient plant is not as likely as with seabeach amaranth, a species with an even narrower ecological niche.

Sea rocket is the only large, common herbaceous plant growing near the foredunes. It is 6 to 20 inches tall with bright green, succulent stems and leaves. The smooth, glabrous, entire, or crenate leaves range from 1 to 3 inches long and 1/2 to 1 1/2 inches wide.

Flowers are arranged in racemes that elongate as the fruits mature. The racemes often reach a length of 8 inches. Pale lavender to white flowers are 1/4 inch across and possess 4 sepals and 4 petals. Bees, flies, beetles, moths, and butterflies pollinate the flowers.

Botanically, the fruit of sea rocket is a silique distinguished by the presence of a horizontally transverse joint separating 2 seeds enclosed in a dry, corky, lightweight pod. The shape of the transverse joint is nearly flat; the fruit is 4-angled, and the top and bottom are similar in shape. The 1/4-inch-long seeds are orange-tan to dark brown, laterally flattened, and ovoid.

The lightweight and buoyant top seed breaks away from the plant and is dispersed by wind or water. The lower portion of the fruit typically remains on the plant and germinates in place if buried by sand accumulating around the dead stem.

Authorities consider sea rocket a “winter annual” in the Carolinas coastal setting: seeds germinate in late summer or early fall and overwinter as small plants. During the following spring and continuing throughout the early summer, the plants flower, set seed, and die. North of the Carolinas, a closely related species, northeastern sea rocket (Cakile edentula) reflects the typical annual habit of spring germination followed by summer flowering.

Sea rocket requires full sun and well-drained sandy soil. It tolerates salt aerosols and low soil nutrients. A poor competitor, it occupies the sparsely vegetated wrack line with plants such as northern saltwort, seabeach amaranth, and northern seaside spurge.

The shape of the transverse joint in the fruit aids in differentiating between the two native coastal Carolina species of sea rocket. In northeastern sea rocket, the lower portion of the silique is deeply notched— clearly V-shaped—and the upper portion is more rounded, almost balloon shaped. The ranges of the species overlap in northern North Carolina.

Marsh Pink

Sabatia Stellaris

- Family: Gentianiaceae (Gentian)

- Other Common Names: Sea pink, salt marsh pink, annual sea pink

- Range: Coastal: Massachusetts south to Florida and west to Louisiana

- Habitat: Dune swales, maritime grasslands, and upper edges of brackish and salt marshes

- Habit: Annual herb

- Flowering/Fruiting Period: FL July-September; FR August-November

- Wetland Status: Obligate Wetland Plant

- Origin: Native

While many plants flaunt attractive flowers with a single color, marsh pink displays a striking flower revealing petals with touches of pink, red, yellow, and white that create an interesting and attractive star-shaped center. Occasionally, this species grows in such profusion that the plants turn acres of maritime grasslands into a multicolored display of flowers swaying in the summer breeze.

Marsh pinks are 6 to 20 inches high with slender, erect, loosely branched stems. Leaves, ranging from 1/2 to 2 inches long, are oppositely arranged, simple, entire, glabrous, and sessile.

Each flower grows on a single pedicel. The 1-inch-wide flowers have 5 short sepals and 5 petals. The stamens and style are yellow. Bumblebees and other small bees such as sweat bees pollinate flowers. Each fruiting capsule contains about 100 tiny black or brown seeds.

Marsh pink is salt tolerant and commonly associated with brackish environments. It frequently grows amid sea ox-eye, sea lavender, saltmeadow cordgrass, dune finger grass, beach blanket-flower, saltmarsh fimbristylis, and southern seaside goldenrod.

The plant provides nectar for pollinating insects, and various herbivorous insects feed on parts of the plant.

Propagation is only by seeds.

Unfortunately, the plant is not commercially available. Collect seeds only where marsh pink is growing in abundance; avoid overcollecting and depleting the annual seed crop. The seeds are tiny, tiny, tiny; just a few seed capsules will generate a lot of seeds!

Marsh pink is either “endangered” or “threatened” in states at the northern limits of its range (Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York). This is due, in part, to the expansion of the invasive species common reed into habitats occupied by marsh pink.

Occasionally, we find a similar species, perennial sea pink (Sabatia dodecandra), in brackish or freshwater marshes in the coastal Carolinas. Its flowers are twice as large and have 9 to 11 petals.

Sea oats

Uniola paniculata

- Family: Poaceae (Grass)

- Range: Virginia south to Florida and west to Texas and Mexico; also Bahamas and Cuba

- Habitat: Dunes and dune swales

- Habit: Perennial graminold

- Flowering/Fruiting Period: FL June-July; FR July-November

- Wetland Status: Facultative Upland Plant

- Origin: Native

Sea oats is a botanical superhero. It can survive rapid sand burial, drought, high winds, salt aerosols, saltwater inundation, high temperatures, and full sun, so it is uniquely adapted to the Carolinas coastal dunes.

Sea oats, a warm-season grass, thrives in a range of shore habitats ranging from the wrack line landward to the seaward edge of shrub thickets and maritime forests. In fact, it rarely occurs inland from the coastal dunes. The plant is the principal dune-building and sand-binding grass of the southeastern United States. It is planted extensively to stabilize sand along shorelines disrupted or eroded by natural or human changes, such as by hurricanes or development.

Sea oats is a coarse rhizomatous plant with an extensive network of near-surface roots complemented by deep, sand-binding roots. Culms arise from the rhizomes that extend laterally and root at nodes when buried by sand. Sea oats tolerates sand burial up to 3 feet per year, with stem growth and tillering stimulated by this burial.

The glaucous green leaves gracefully arch upward from their underground origin, and the tips return to the sandy surface in a seemingly unorganized fashion. Sea oats leaves grow up to 24 inches long and 1/4 to 1/2 inch wide and have a long, tapered point. During protracted drought, leaves roll inward, forming long tubes that reduce water loss through the stomata.

The sea oats inflorescence is the most familiar and striking feature of the plant. It is composed of dozens of spikelets crowded at the top of 3- to 6-foot culms. The spikelets are flat, 1/2 to 1 1/2 inches long, 1/2 inch wide, and composed of 10 to 20 florets. During their maturation, sea oat spikelets turn from blue-green to golden brown. Most flowers do not produce seeds, and research scientists report that spikelets average fewer than 2 seeds each. Spikelets persist on the culms well into the winter. Over time, wind, water currents, and animals disseminate the spikelets.

Birds and small mammals, such as song sparrows, red-winged blackbirds, and mice, consume seeds not quickly buried by blowing sand. Seeds usually remain in the spikelet, as evidenced by the presence of a spikelet almost always entwined by the roots of each germinating seed.

The primary method of reproduction is vegetative growth through rhizome extension and bud formation. Vegetative vigor and flowering of sea oats decrease noticeably in the absence of sand accretion.

The plant grows poorly in habitats with a high water table or continuously saturated soils. Human impacts such as trampling, off-road vehicle use, and urbanization harm the growth and development of sea oats.

It is illegal to collect plants or inflorescences of sea oats in most municipalities in North Carolina and South Carolina without a permit.

Sea oats is available from dune plant growers in the coastal Carolinas. Plugs should be planted in spring or early fall.

Read a Q&A with Paul E. Hosier here, and listen to his interview with Mike Moore on Rockingham County Radio here.

This article was published in the Summer 2018 issue of Coastwatch.

- Categories: