RHYTHMS OF THE SEA: Griffith Chronicles Coastal Change

As an anthropologist, David Griffith documents change in North Carolina’s coastal communities as they meet this new century head on. As a poet, Griffith looks beyond the statistics to the rhythm and cadence of lives in the midst of change. He sees patterns in the ecosystems and songs in the stories of days gone by.

During the course of his studies and fieldwork, Griffith has been mistaken for a CIA agent in Latin America and a “revenue man” on fishing boats in North Carolina. Often his laid-back approach and basic questions convince subjects that he couldn’t really be a college professor.

“I am not a very threatening person — and I am genuinely interested in their stories,” says Griffith, a North Carolina Sea Grant researcher from East Carolina University. “I love spending time with people who are different than I am.”

Those differences are quickly set aside when coastal residents realize he is there to listen, not lecture, says Susan West of Buxton. “David is very good at listening — and hearing what people have to say,” says West, who has a family perspective on commercial fishing.

In his new book, The Estuary’s Gift: An Atlantic Coast Cultural Biography, Griffith not only reports results of his formal studies, he also weaves the stories of very different people who are linked by their ties to the coastal waters.

His essays tell of slaves who escaped through hidden canals and whaling families who lived in Diamond City. More modern stories include those of Mexican women picking blue crab, commercial fishers frustrated by regulations, and recreational anglers competing in high-dollar tournaments.

Griffith’s study of changes in coastal communities goes hand-in-hand with the biological and chemical studies of coastal ecosystems, says Ronald Hodson, North Carolina Sea Grant director.

“We need to understand not just the biology, but also the human involvement,” Hodson says. “We can’t do any management scheme without knowing the human relations and interactions.”

Bill Queen, director of ECU’ s Institute for Coastal and Marine Resources, agrees.

He points to the dramatic change that has come to the Outer Banks in the past 10 years. “From Nags Head to Corolla — now it looks like a suburb of Los Angeles,” he says.

While marine scientists are evaluating the environmental impact of such change, attention also must be focused on societal forces that drive the change. Griffith, working with ECU sociologist Jeff Johnson, has given North Carolina a reputation of being on the cutting edge of social science research on coastal topics, Queen says. “Programs in other states use this as a model,” he adds.

And, their research results have provided critical input for state advisory panels, legislators and regulators. “It paints a true picture of what is taking place,” says Twila Nelson, who met Griffith when she served on the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission.

West, who served on the Fisheries Moratorium Steering Committee in the mid-1990s, agrees. “I’ve been impressed with the perspective he’s brought to discussion of fisheries issues,” she says. “You’re not just talking about managing fish, you are talking about managing people and communities.”

Coastal Studies

Griffith, now 48, arrived in North Carolina in 1983 to work on a research project on underutilized fish species. Jim Murray, then extension director for North Carolina Sea Grant, and Johnson led the work, which was funded by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Griffith prepared a detailed format and sequence for interviews of fishers along the coast. He also conducted the interviews along the docks and sent regular reports from the field. But the reports showed a certain style from Griffith, who had attended the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

“I used to love reading his field notes,” recalls Murray, now director of extension programs for the National Sea Grant College Program. “He would send us these elaborate, flowery field notes. He would muse about the sunrise …. He must have had a great time going back to the motel room to write them up.”

While Griffith’s poetry background sparks his academic prose, the anthropology field experiences also provide fuel for his creative writing, Murray explains. “He has been able to marry the two disciplines. Each helps the other,” he says.

That first project gave Griffith an introduction to North Carolina issues, and introduced him to the Sea Grant program. It also sparked continuing collaboration with Johnson. Such collaboration lends integrity to the projects, Griffith says.

And it splits the workload. “My strengths are analytical. His strengths are in writing. We work together,” Johnson says. In fact, an ECU publication profiled the pair as a “dynamic duo,” with Johnson as the outspoken numbers cruncher and Griffith as the quieter wordsmith.

Since their first project together, all of their collaborative efforts have included an outreach or extension component. “We are trying to change something for the better,” Johnson says.

Murray recalls Griffith going out of his way to participate in public forums or to make public presentations of findings. “David very much understands the value of extension,” he adds.

Johnson and Griffith continue to collaborate — including a new two-year Sea Grant project that will document the technical environmental knowledge held by commercial fishers and others in the seafood industries. “They monitor the resource for us,” explains Griffith, repeating a theme that runs throughout The Estuary’s Gift:

“Because fishers move from one territory to another to fish, shift from crab pots to shrimp trawls or from gill nets to clam rakes, because they land croaker during one season and mullet or blue crabs during another, they are the group of people best situated to monitor the health of coastal rivers, sounds, ocean waters and estuaries. They routinely spot and report incidents of pollution. They experience the waters, often taking note of changes that are too subtle and require too many observations for anyone but fishers to notice. They tickle the bottom with crab pots, assess the condition of sea grasses snarled in their nets, witness in the debris of their catch the Litter of tourists and the natural trends of biological diversity.”

For example, Griffith tells the story of a scallop fisher he calls Davis Evans, who hails from the Bogue Banks in Carteret County. Evans and his father-in-law bring in the catch one day, then spend the next day shucking alongside family and neighbors. It is Evans who takes Griffith out for a day of scalloping and jokes to other fishers that he has a revenue man aboard.

“Each time Davis pulled the net into his skiff, he examined its contents. More than once he showed me small organisms that resembled insect larvae and commented that they were more or less plentiful than they had been in past seasons. To me, they all looked the same,” Griffith writes.

And the fishers themselves feel a part of the ecosystem, as one Stumpy Point fisher explains. “I’m 63 years old. I can’t hardly remember when I wasn’t fishing. I’m as much a part of this sound as the things that live in it.”

Griffith writes of the close ties between coastal communities and the sea — from precolonial Algonquins to the thriving herring fisheries in the early 1900s. Now young adults are less likely to have such a strong connection to full-time fishing. And even middle-aged and older fishers take land jobs to make ends meet — often losing the independence of fishing and their intimate links to the water.

“Full-time fishers see it happening all the time. They notice that fishers who leave fishing for a full-time job ashore, phasing back to part-time fishing, slowly lose the ability and perhaps the motivation to continue monitoring and protecting the resource,” Griffith writes.

Picking Out Patterns

Griffith’s studies of the seafood processing industry began with a Sea Grant project in 1985. He watched as scallop houses remained family-oriented operations, while crab processors began hiring Mexican women on special visas. “I am still studying seafood processing. There has been fascinating change,” he says.

In fact, in his book, the chapter on “Vanishing Women” is one of his favorites. “Why vanishing? Because, historically, North Carolina’s crab pickers slipped into the recesses of coastal counties after leaving the plants. Daily and at the end of the season, they returned to neighborhoods along back roads and inside small coastal communities that few people who eat the fruits of their labor will ever see,” Griffith writes.

But by the mid-1980s, fewer local women, white or black, were seeking the seasonal picking jobs that would send them home with the smell of crabs and a paycheck based not on hours, but on the pounds of meat picked. Griffith is able to compare the introduction of the workers on H2 visas from Mexico to the use of foreign workers in other industries including apple picking and sugar cane harvesting.

The crab-plant owners’ choice to use the Mexican workers came not just from cost accounting, but more importantly as a means of labor control, Griffith explains. With an H2 visa, the foreign worker can work for only one employer for one season.

Griffith draws a comparison between the earlier relationships between plant owners and local crab pickers, and not surprisingly, he uses the sea to explain. ”We find a similar relationship between groupers and wrasses around ocean reefs,” he writes.

Normally, the two species get along, with the wrass getting meals by cleaning the grouper’s scales. But, as in nature, such relationships sometimes shift.

In the case of the crab plants, alternative opportunities for the local workers — such as jobs in the tourism industry or classes at nearby community colleges — reduced their desire to take the seasonal work. With the H2 workers, plant owners could set their plans for the entire season.

Stories of the Sea

Griffith’s studies also include community reactions to proposed changes in fishing regulations and to challenges presented by Pfiesteria, a sometimes toxic dinoflagellate first discovered in North Carolina waters.

The diversity of topics is invigorating. “North Carolina fisheries are so complex and interesting, you tend not to get bored,” he says.

Griffith also participates in the Southern Coastal Heritage Program that provides workshops to help teachers share lessons of the unique ecosystems and communities along our shore. Even though he is “not a big one for sitting on committees,” he enjoys the lively exchanges generated by the interdisciplinary panel.

The variety of his experience is apparent in The Estuary’s Gift, a summary of Griffith’s work through the 1980s and 1990s. The book cites his studies in Florida, Virginia, Puerto Rico, the North Carolina mountains and especially along the North Carolina coast, allowing Griffith to draw parallels between the various locations and industries.

The book also allows him to put the North Carolina coastal experience into historical perspective. In fact, he enjoys the historical research about as much as his fieldwork.

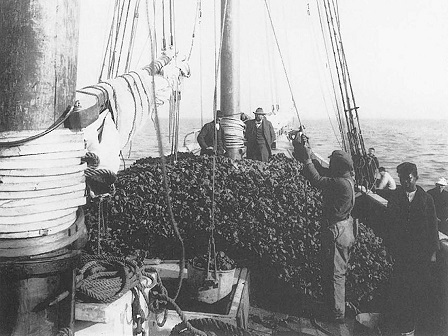

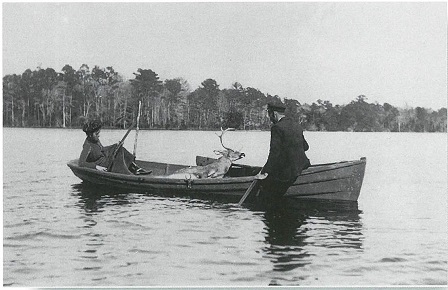

While the book is written in a narrative style without footnotes, he follows the academic tradition of using pseudonyms for the local residents. Thus, he has chosen historical photographs rather than current images to illustrate the various chapters. The archive photos of net fishing and oyster shucking are similar to those in his office and the hallways in the historic Mamie Jenkins Building on the ECU campus.

One of his favorite images is of a couple in a boat with a dead deer. With a bemused smile, Griffith points out that it is the woman, wearing a dress and hat, who is carrying the shotgun in the photo circa 1895. It is obvious that he delights in finding such juxtaposition.

The Estuary’s Gift is his fourth book, and another on fishers in Puerto Rico is in the works.

Griffith still finds time to write poetry and other creative pieces, but you must page through his vitae to learn of the national praise for his creative work. For example, his short story “Devil’s Workshop” took second prize in Story magazine’s 1998 competition.

That doesn’t surprise ECU colleague Margie Gallagher. She knows that his poetry has earned national recognition. But as in his academic work, the projects are not done for praise or glory. “He doesn’t need the approval of others,” she says.

Then again, poets tend to be underappreciated in our society, she adds.

This article was published in the Early Summer 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.