As spring turns into summer, North Carolina Sea Grant researchers have a watchful eye on coastal waters — and they will have some high-tech eyes as well.

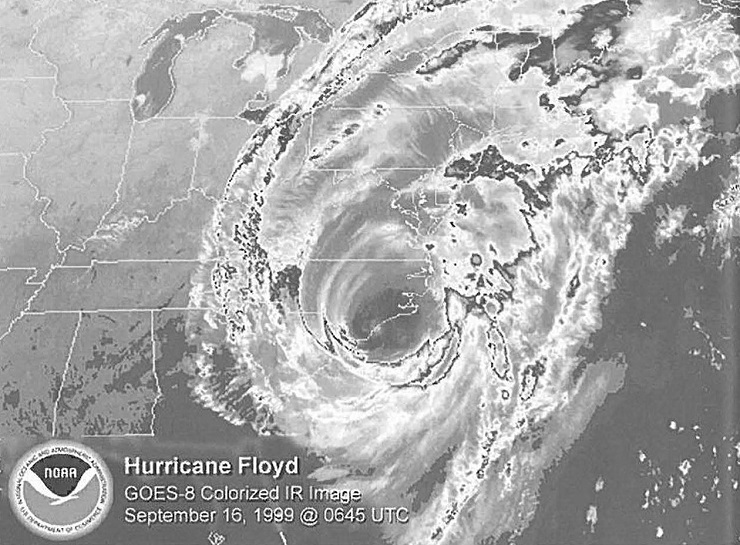

Efforts to determine lingering effects of unprecedented flooding last fall will be bolstered by monitors on state ferries, remote imagery from the Sea Wifs satellite of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and permanent monitoring stations along the Neuse River and estuary.

And there may be one silver lining in 2000 to the devastating hurricane season of 1999: Outbreaks of toxic Pfiesteria are usually low after major storms.

“I am hoping we will have a quiet year,” says JoAnn Burkholder, an aquatic botanist at North Carolina State University and expert on Pfiesteria.

The flooding that accompanied Hurricane Floyd had identifiable short-term effects on coastal waters: an increased load of nutrients and decreased levels of oxygen and salt in estuaries.

While the fast-moving Cape Fear system may have recovered fairly quickly, the turnover is much slower in the Pamlico Sound, a major nursery area that is still showing signs of stress.

“We are finding much smaller yearlings. Fish that should have been 6- to 8- inches by spring were still only 4-inches long. Clearly, their reduced growth is linked to the stressed environment,” Larry Crowder, a marine biologist at the Duke University Marine Lab, says of sampling in the Pamlico.

Crowder and others will continue to monitor various species as they advance through the life cycle this year. He expects to see other signs of prolonged stress on fish that were trapped in the sound when Floyd’s freshwater plume arrived.

Such data would support laboratory findings of NC State zoologist James Rice, graduate student Regan McNatt and Edward Noga of the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. The team studies the impact of low levels of oxygen — known as hypoxia — on the feeding, growth and immunity of juvenile estuarine-dependent fish.

They found that fish exposed to low-oxygen rates for prolonged periods had reduced growth rates and weakened immune systems.

“Although it is well-documented that acute hypoxia can lead to fish kills, few studies have measured the direct effects of sublethal hypoxia on fish,” says Rice.

“Increased vulnerability to disease may lead to greater mortality, and decreased growth can also reduce production by fish populations.” In particular, the study found that natural antibacterial activity decreases as dissolved oxygen levels decrease.

SIGNALS AND CYCLES

Why did some commercial fishers report record landings in the fall, while others qualify for disaster assistance because of limited catches?

Some researchers and state officials suggest that heavy rains from Hurricane Dennis — which lingered on North Carolina’s coast for two weeks — may have dumped enough fresh water into the Pamlico and upper estuaries to signal more mature sea life to leave the sound. Some fishers were well-positioned for the bounteous catch. Changes in traditional fishing grounds could continue.

Thus researchers also are following the fate of the larval fish that are transported from the open sea into the sound’s nurseries in March and April.

Will the low salinity levels hinder the larval fish, including croaker, flounder and pin fish that support North Carolina’s lucrative fisheries?

Or, Crowder asks, “Could larval fish actually benefit from the additional nutrient levels that remain on the bottom of the sound and estuaries?”

Additionally, upriver habitat is still recovering from the triple dose of storm upheaval. If sea grasses — habitat for gag grouper — do not make a comeback, this year’s class of fish could be affected.

The jury still is out on overall effects to North Carolina fisheries, researchers and state officials agree. Mother Nature’s final answer will depend on the prevailing weather in spring and early summer.

Warm sunny days could feed algal blooms with more light. Organic materials and fungi will use oxygen to decompose. A wet, warm spring and summer could add more fresh water and nutrients.

What is the best case scenario? A dry and windy spring could evaporate fresh water trapped in the Pamlico and promote its recovery, Crowder says.

The researchers find themselves in new territory as they evaluate the cumulative effects of Hurricanes Dennis, Floyd and Irene, which hit the North Carolina coast within a four-week span in late summer and early fall. Scientists have limited data from 1954-1955 — when four hurricanes hit North Carolina in a 12-month period — to help predict how the fisheries will recover.

“This is an opportunity to do groundbreaking research that will help predict, but more importantly help guide management policies of how to manage our resources at a time of greater levels of disturbance,” Crowder says.

THE PAMLICO PUZZLE

A small armada of scientists will continue studying the hurricane effects up and down the coastline. The interdisciplinary effort — including several Sea Grant-funded studies — began with a rapid response.

“We virtually commandeered the Duke and UNC research vessels,” Hans Paerl, a Sea Grant researcher at the University of North Carolina’s Institute for Marine Sciences, recalls the days after Floyd hit.

Researchers teamed up with state agencies to launch an immediate assessment of water quality and fisheries habitat in the Pamlico Sound — the nation’s second largest estuary and deemed by many to be the state’s most valuable aquatic resource.

The Pamlico processes nearly half of the state’s freshwater runoff via its subestuaries — Neuse, Pamlico, RoanokeChowan-Albemarle. But that process is slow — with a mean water retention time of about one year, Paerl says.

Academic researchers parlayed their resources with teams from the state’s ongoing Neuse River Modeling and Monitoring Program (ModMon), and NOAA’s fisheries lab in Beaufort. The fleet of researchers already was on the scene with cameras and monitoring devices as Floyd’s deluge inundated the sound and swollen freshwater tributaries, and flushed a dark brown plume of sediments and organic waste into the Pamlico.

Early measurements caused concern because the salinity levels of the Pamlico plummeted. Bottom-water measurements indicated low oxygen and elevated inorganic nitrogen and algal production levels in the western sound. The Pamlico had virtually stratified, with a freshwater layer atop a salt-water bottom layer. Trawls of the region yielded dead and dying shrimp and blue crabs, and bloated fish with tail rot, skin sloughing and lesions.

Hurricane Irene arrived as a mixed blessing. Though already-flooded eastern North Carolina was wont to receive another dousing, Irene’s winds “stirred” the Pamlico, mixing salt and fresh waters and temporarily releasing oxygen to stressed finfish and shellfish.

Stratification reoccurred and oxygen and salinity levels remain lower than normal, but massive fish kills did not happen. And through the winter months, signs of disease dropped.

But by the spring, the sound was still fairly fresh and chlorophyll levels were elevated in the nutrient-rich waters. “What normally happens in the Neuse in late February has moved into the sound,” says Paerl, who is monitoring algal growth.

“There is potential for freshwater species to move into the sound.”

Burkholder’s team also is monitoring the river, estuary and sound with the placement of automated platforms that will offer a stream of data rather than sporadic sampling. “It’s the difference between a snapshot and a movie,” she says.

Unlike the fish kills that came with Hurricane Fran, the sound had oxygen levels on the rebound eight weeks after Floyd, Burkholder says. But, Floyd’s legacy may be a “flanking effect” of nutrients deposited in the estuary.

“We will continue to track water and biological quality in the Neuse and western sound during the coming year, with major focus on the estuary in evaluating the extent of delayed impacts that may be sustained from the hurricane,” she says.

CAPE FEAR QUESTIONS

While the Pamlico Sound has a long retention rate, the Cape Fear River moves quickly toward the coastal ocean. University of North Carolina at Wilmington researchers Martin Posey and Troy Alphin study the effect of storms and hurricanes on bottom communities in the Cape Fear River.

“The passage of hurricanes Fran and Bonnie were associated with dramatic declines in bottom communities,” says Posey, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

“The animals did not recover until the following summer. Preliminary data suggest that an abundance of bottom animals seemed to recover more quickly after Hurricane Floyd.”

Meanwhile Larry Cahoon, who heads an interdisciplinary coastal ocean program at UNC-W, investigated the effects of Hurricane Floyd flooding on ocean water quality.

The flood caused the highest single daily discharge of the Cape Fear River in the last 50 years. After sampling the river and its plume, Cahoon found that nutrient concentrations weren’t any higher than the same period the year before.

“Although large quantities of animal and human waste were likely washed into the Cape Fear by hurricane flooding, the large rainfall volume diluted these contaminants, preventing more serious water impacts on the coastal ocean,” says Cahoon.

For statistics on Hurricane Floyd, check the National Climatic Data Center’s site on the Web: www.ncdc.noaa.gov and follow the links to the climate extremes and satellite images.

This article was published in the Early Summer 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

FLOYD’S ECONOMIC IMPACT TALLIED

East Carolina University researchers estimate businesses in the coastal plain suffered $4 billion lost revenue and another $1 billion in physical damage. In spite of their losses, most businesses participated in community relief and recovery efforts, contributing an average of $5,800 to those programs.

The ECU team, with funding from North Carolina Sea Grant, is studying the socioeconomic impact of Hurricane Floyd on businesses in the 44 hardest-hit counties. They report three-fourths of the businesses in those counties shut down because of the storms and floods. The shutdowns varied from five to eight days depending upon the locale.

Months after the floodwaters receded, ripples of loss are still being felt on the economy. Almost 10 percent of the businesses that experienced some storm damage reduced their labor force. Projected across the region, that adds up to about 31,000 lost jobs.

The study, conducted by faculty members from sociology, economics and the university’s Survey Research Laboratory, reflects telephone interviews with more than 2,400 businesses. Construction, manufacturing, transportation and utilities, wholesale, retail, tourism, agricultural and service sectors were sampled.

Most businesses survived the storm, and are back in operation. However, small businesses in the most severely impacted region have not resumed operation.

Road closures had the longest impacts on businesses that identified infrastructure problems. Road problems were especially hard on medium and small businesses in severe- to moderate-impacted counties. Loss of water and power had the second and third greatest impact.

Most businesses reported having some insurance, but one out of every six small businesses had none. While most had liability, property and casualty and fire insurance, most were not insured for loss of revenue or floods. Less than half of the businesses reported having insurance that covers the replacement cost of their losses.

For 375 firms reporting physical damage, the average cost was nearly $40,000.

Expansion plans have been put on hold by most businesses. Before the storm, nearly 15 percent of the small businesses and 17 percent of the medium-sized businesses had plans to expand. This dropped to 12 percent and 5 percent respectively after the storm. Before the storm, about 25 percent of the large businesses had expansion plans. After the storm, this dropped to 7 percent.

ECU faculty members who participated in this study include John R. Maiolo, John C. Whitehead, Marieke Van Willigen, Robert Edwards, Paula Harrell and Kenneth Wilson, and graduate students Kelly Arena and Genuan Gunawardhana.

This article was published in the Early Summer 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: