It’s early in the morning as East Carolina University professor Stan Riggs stands on a wooden platform and surveys the towering sand dune at Jockey’s Ridge State Park.

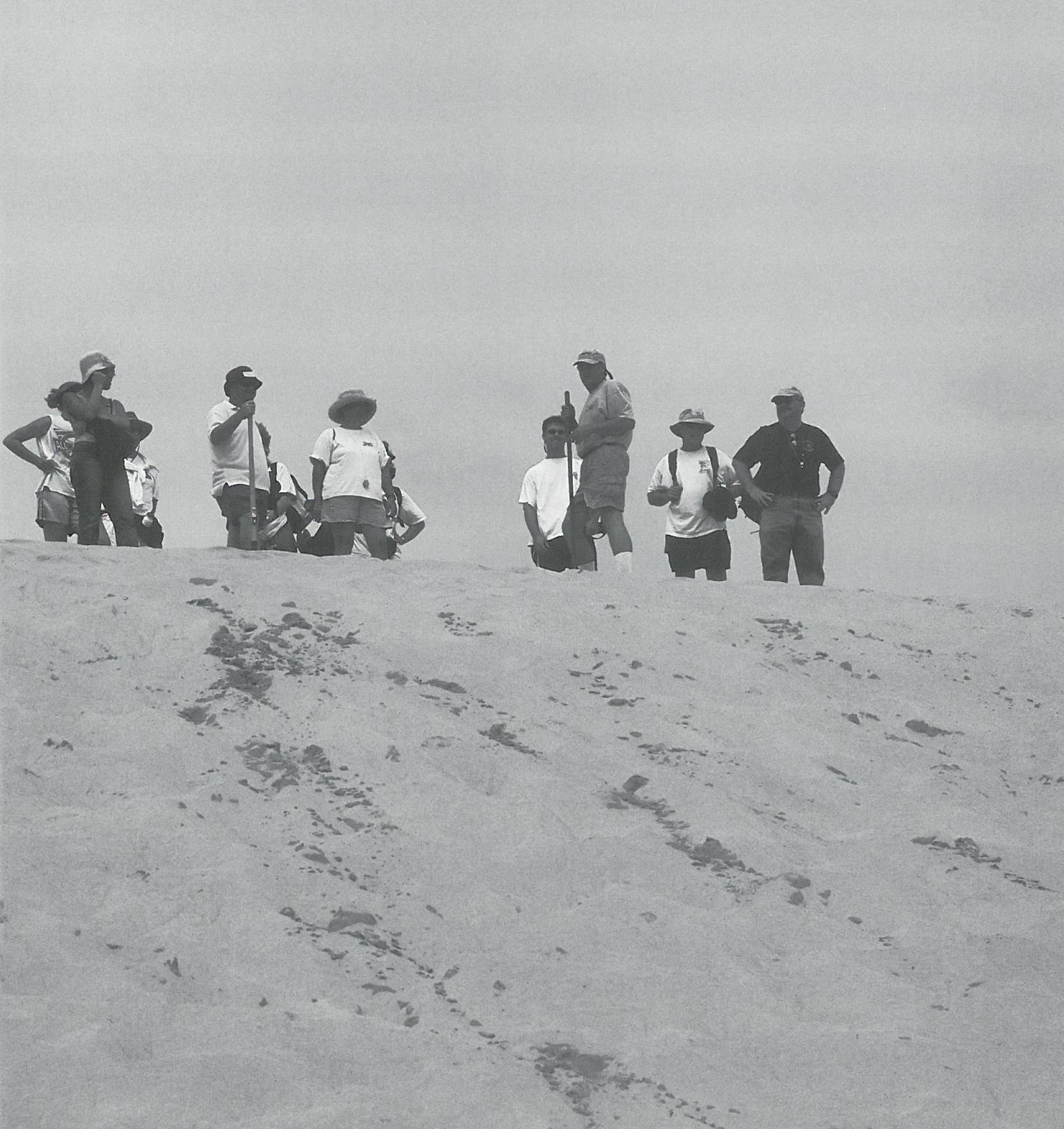

Before trekking up the beige dune imprinted with shadows and hundreds of footprints, Riggs encourages a group of teachers and students to “envision how much sand they will push down.”

“A lot of people go up this hill each day,” says Riggs, a North Carolina Sea Grant researcher. “When you climb the dunes, think of the process and envision the volume of sand you are pushing down. If you put 10,000 people on the hill and each one goes up and down five times, the human force becomes a significant part of the dune dynamics. We are pushing down the dune.”

Over the years, Riggs says, the dune system at Nags Head has shrunk in size from 156 feet in the 1950s to 90 feet today.

The erosion of Jockey’s Ridge is just one lesson that Riggs imparts to North Carolina high school science teachers and students during a North Carolina Sea Grant workshop.

During an eight-day visit to the Outer Banks, Riggs takes 10 teachers and eight of their students from across the state to view barrier island processes and conflicts, including the severely eroding shoreline at South Nags Head.

“It was fascinating going to South Nags Head,” says Flo Gullickson, a Southwest Guilford High School science teacher. “We found a home with an exposed septic system. You could smell the raw sewage. There were lots of sand bags. Some of the homes at South Nags Head are falling in the ocean.”

Teachers and students will incorporate the lessons into earth science materials for North Carolina high school teachers.

Funded by North Carolina Sea Grant, the “Sea-View” materials will relate to the curriculum goals set in the N.C. Standard Course of Study.

Since the 2000-2001 school year, every entering freshman has been required to complete a course in earth/environmental science for graduation. This makes North Carolina one of only two states in the country to have an earth science graduation requirement, according to Bill Tucci, high school science consultant at the N.C. Department of Public Instruction.

“North Carolina has become a model for the whole country,” adds Tucci.

Currently, there is not a good textbook available for earth science teachers, according to the project’s principal investigator Karen Dawkins. “Earth science books focus primarily on principles of geology with little attention to environmental topics,” she adds. “There are probably few issues more critical than those related to our marine and coastal resources.”

A team of high school teachers and students, university faculty, and experts from various state agencies will develop Sea-View earth science lessons that will be in print, on CD-ROM and the Web.

Coastal Hot Spots

To learn about barrier island dynamics, teachers and students investigated issues at five coastal sites: the stabilization at Oregon Inlet, overwash on N.C. 12 between Avon and Buxton, estuarine shoreline erosion at Nags Head Woods, ocean shoreline erosion and urban development at South Nags Head, and dune migration at Jockey’s Ridge.

“We chose the Outer Banks because it provides good examples of barrier island processes and conflicts in North Carolina,” says Dawkins.

For Freedom High School student Eva Lee, this was her first glimpse of the rough waters of the Atlantic. “I just kept looking at the waves,” says Lee of Morganton. “I now understand” the power of the sea, she adds.

This program gives students a unique opportunity to participate in the curriculum process early in their educational experience.

For the project, Dawkins selected experienced science teachers who had participated in Earth-View, a National Science Foundation project that educated earth science teachers about the geology of the Appalachian mountains, piedmont and coastal plains. The select group of teachers received extensive field experience and developed leadership skills.

“Sea-View is a natural extension of Earth-View,” says Dawkins, director of ECU’s Center for Science, Math and Technology Training. “Over three years, 10 teachers have developed a comprehensive picture of North Carolina’s geologic history and the human impacts on our valuable resources. Sea-View is a wonderful opportunity for them to use their knowledge and skills at a different level.”

Dawkins conceived the idea for professional development in earth/environmental materials for teachers in 1999 after conducting a statewide survey of school superintendents regarding the new required course in earth/environmental science.

“Only a small percent of teachers had any earth science background,” says Dawkins. “Almost none had earth science certificates. A large number were biology or chemistry teachers who were asked to teach earth science.”

Although all slots for earth science teachers in the state’s public schools are filled this fall, Tucci says that many teachers are “underprepared.”

“Because earth science includes four content areas — geology, astronomy, meteorology and environmental issues — it is hard to find a teacher who is prepared in all these areas,” he adds. “Staff development efforts like Earth-View and Sea-View are making genuine progress toward preparing teachers to address the environmental issues in the Standard Course of Study.”

Lundie Spence, North Carolina Sea Grant marine education specialist, agrees.

By initiating Sea-View, Dawkins is “taking a new leap in the development of earth science materials for high school and middle school,” says Spence, the project’s faculty advisor.

“Identifying coastal hot spots where natural systems are in conflict — with impacts on people — and then developing lessons makes science relevant,” she adds. “The use of Web and digital technology will make the product more accessible and exciting to North Carolina teachers and students. Other states also will be able to use the materials to compare our state’s hot spots to their own hot spots.”

Experienced Leaders

Dawkins and Riggs bring different expertise to the program.

Since 1990, Dawkins has been providing professional development programs for science teachers in elementary, middle and high school at North Carolina State University and ECU through the N.C. Mathematics and Science Network. Before working at the university level, Dawkins was a high school science teacher for more than 20 years.

On the field trip, Dawkins is both a mother figure and mentor to the teachers and students. She leaves the field trips early to prepare home-cooked meals for the participants. During meetings, she encourages students and teachers to work together and collect good data, including rich descriptions and accurate sketches and measurements on their field trips.

“I find that the work with teachers provides a tremendous intellectual challenge and boosts my creative juices terrifically,” says Dawkins.

Riggs brings a research perspective to the teachers and students.

For 35 years, he has studied the origin and evolution of the world’s continental margins, including climate and sea-level change. His work has taken him from coastal plain rivers in North Carolina to the outer edge of the continental shelf.

Riggs also has taken numerous teacher groups on field trips. Last summer, he led an Earth-View trip at the juncture of the coastal plain and piedmont in northeastern North Carolina. In 2000, he gave teachers a first-hand look at the aftermath of Hurricane Floyd in a Sea Grant-sponsored workshop, a spinoff of Operation Pathfinder.

“This is the third trip I have taken with Stan,” says Martha Buchanan, a teacher at Freedom High School in Morganton. “He is doing a great service to North Carolina by putting material in layman’s language so high school students can understand it.”

When educating students and teachers about coastal processes, Riggs is passionate and energetic. For almost four hours straight, he leads students and teachers over Jockey’s Ridge and through Nags Head Woods. The only time he stops is to pick up a piece of charcoal or sand or show a map of aerial photos of development around Nags Head from 1932 to today.

“These photos are like watching a person grow up,” he says. “The 1932 photo shows when the first road was built and the dune at Jockey’s Ridge was very large and expanded over a large area.”

By the 1960s, there was some development around Nags Head.

Ten years later, contractors began building houses on top of dune fields, including portions of Jockey’s Ridge and Seven Sisters dune fields, eventually eliminating the Seven Sisters dune field, according to Riggs.

“The water lines blew out, and septic systems filled with sand,” adds Riggs. “Every house had to be bulldozed. Today’s aerial photos show very little undeveloped land area.”

Maritime Forest

At Nags Head Woods Ecological Preserve, Riggs leads the teachers and students, who are loaded down with backpacks and water bottles, deep into the diverse maritime forest, managed by the Nature Conservancy.

When the group gets to the edge of the forest, they trek through a vast marsh to a severely eroding estuarine shoreline.

“Much of the marsh doesn’t exist anymore,” says Riggs. “The shoreline erosion is a product of rising sea level. The loss of wetlands and uplands in coastal North Carolina is between 1,000 and 2,000 acres per year.”

After looking at the shoreline, the group wades through the brackish water and looks for eroded blocks of peat.

“High-wave energy breaks off large blocks of peat,” says Riggs.

For the teachers and students, the hands-on experience is invaluable. “It makes science a little easier when you can apply it to everyday life,” says Kim Whitley, a Perquimans County High School student.

John Blake, a North Whiteville Academy teacher, agrees. “This experience will give me some new strategies to take back to my community,” says Blake. “I will be applying some of the concepts learned to the Lumber River Basin and wetlands in Columbus County.”

After the field trip, the students and teachers divide into groups.

The next day, they conduct beach profiles. The South Nags Head group takes photos of homes in the surf with septic problems.

“We learned so much about beach erosion rates because it is so pronounced at South Nags Head,” says Buck Bunch, Perquimans County High School teacher. Some of the cottages that are oceanfront lots now were on the second and third row from the ocean 15 years ago, he adds.

Team Work

By creating a partnership between students, teachers and university people, you get a much richer product, according to Dawkins.

“We couldn’t have assembled a better group of people for the task,” she says. “The days were long and hard and hot — but the teams performed their work with great enthusiasm. We didn’t have one whiner in the group. As a result of their work, we have a treasure trove of observations, measurements, photos, videotapes and interview notes that will serve as the raw materials for the finished product.”

By the end of the week, the students and teachers are ready to interview elected officials, business people and government representatives.

“We learned that you need to look at different perspectives when dealing with an issue,” says Bunch. “Scientists, property owners and officials have different viewpoints. You need to get everybody’s input to make a good decision.”

Next summer, the materials will be refined. During the 2003-2004 school year, teachers will test the products, which will include inquiry-based lessons.

“By the end of the project, approximately 60 teachers will be using the materials with more than 1,800 students,” says Dawkins.

She hopes that the new earth science resources will give students a broader perspective about the North Carolina coastal environment.

It’s not hard to see that many of our citizens have misused some of our most valuable natural resources, but this is due primarily to a lack of education, says Dawkins. “One way to solve this problem is to help students weigh important issues,” she adds.

“The ultimate goal is to develop informed citizens, beginning with high school students and teachers.”

This article was published in the Holiday 2002 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: