SEAFOOD SAFETY: N.C. Products Get Clean Bill of Health

Before Wayne Mobley begins a state inspection of an eastern North Carolina crab company, he washes his hands in the picking room.

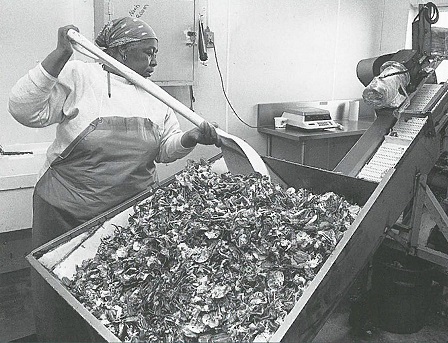

Then Mobley glances around at elderly women sitting around stainless steel tables, knives in hands, swiftly picking meat out of steamed blue crabs. Signs are posted in English and Spanish because many foreign workers will arrive on special visas later in the year.

“Those workers have a language barrier,” says Mobley, regional environmental health specialist, N.C. Division of Environmental Health, Shellfish Sanitation Section. “Some plants have to teach workers how to sanitize properly and the proper way to use processing equipment.”

While Mobley looks around at the workers’ aprons to make sure they are clean, the women continue picking crabs. Workers must pick the meat at a rapid pace.

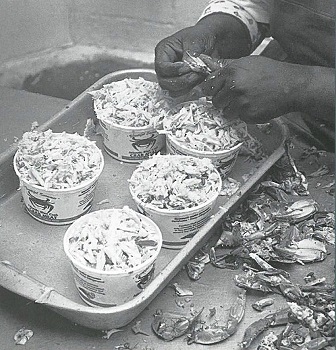

“The state law requires that the plants have three-and-a-half hours from the time the crabs are placed on the table as whole cooked crabs until the product is cooled down in cups to 40 degrees,” Mobley says of the cooker-to-cooler cycle.

Since crabmeat temperature is critical, he places a thermometer in a cup of just-picked crabmeat. The meat is 62 degrees,” he says. “The crabmeat temperature usually stays in the low 60s. During the summer, the temperature may elevate slightly.”

Mobley then rubs his hand under a table and finds traces of crabmeat. “This table needs scrubbing underneath,” he says to a supervisor. “If a table is too dirty, I make the manager take the crabs off the table and re-sanitize it.”

His inspection is thorough and precise. He even looks on the floor to make sure no claws or crabs have fallen. And he checks the machinery, from canning to pasteurization — a cooking process that extends the shelf life of crabmeat.

Throughout the plant, Mobley only finds a few minor violations, including stray cats eating scraps out of trash cans near the loading dock and a hose on the picking room’s floor.

“The crab industry is a big business and operates as such,” says Mobley. “We tell them what is required, and the owners do what is asked.”

The state inspection — which is required quarterly for all crab and molluscan plants and monthly while crab plants are operating — is just one aspect of seafood safety in North Carolina. From dock to processing tables to restaurant kitchens, safety is a constant factor.

All plants that process molluscan shellfish, including clams, oysters and mussels, and all crustacean plants must follow the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) safety program known as Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP).

Initiated in 1997, HACCP is required for all seafood dealers, processors and importers and aims to minimize hazards in seafood — such as histamine poisoning in certain fish such as tuna — before the seafood reaches the consumers.

The N.C. Department of Agriculture has an agreement with the FDA to do HACCP inspections of some of the state’s seafood facilities, other than the shellfish dealers. The department also monitors the facilities’ manufacturing and housekeeping standards.

Are the state and federal regulations protecting consumers from unsafe seafood?

“Fish and seafood from North Carolina waters are very safe to eat,” according to Barry Nash, North Carolina Sea Grant seafood technology and marketing specialist.

There is no documented evidence of illness caused by North Carolina-produced shellfish and shellfish products, according to the Shellfish Sanitation Section in Morehead City.

However, there have been a few reported cases of a foodborne illness related to prepared fish, says Joe Reardon, food compliance supervisor for the N.C. Department of Agriculture. In January 1999, Reardon says two people were reported ill from histamine poisoning after eating tuna salad at a Wilmington restaurant.

For healthy individuals, the nutritional benefits of seafood, such as omega-3 fatty acids — which have been shown to prevent heart disease — far outweigh safety concerns. The risk of becoming sick from eating seafood is one in 250,000 compared to one in 25,000 from eating poultry, according to the FDA’s Center for Food Safety Study in 1991.

“Consumers equate product quality with food safety,” says Nash, whose office is at the North Carolina State University Seafood Laboratory in Morehead City.

“Many people assume that seafood is not as safe as beef and poultry products. Seafood that is properly cooked is as safe as any cooked beef or poultry product.”

Mobley says state regulations protect the consumer as well as the industry. In addition, he says the section helps the seafood industry put out a good product.

While making routine inspections and yearly recertification checks, environmental health specialists encourage plants to upgrade their processing facilities and equipment.

“In the last 1O years, the number of crab plants has decreased, but crab processing still leads the way in the seafood industry,” says Mobley.

Several North Carolina crab plants have installed sleek, modern equipment. At CryoTech Food Systems in Aurora, every live crab travels through a tunnel where it is cooked and frozen. The company also uses nitrogen freezing.

Carolina Seafood Inc. in Aurora has remodeled its facility to include fiberglass walls that are easy to clean and air conditioning in the culling rooms where crabs are separated. “We cool crabs as soon as they come off the boat,” says owner Etles Henries. “That way we have no spoilage.”

HACCP STANDARDS

In addition to state regulations, crab plants and other seafood processors must follow HACCP’s stringent safety standards. Under the plan, companies first scrutinize their operations for “hazards that are reasonably likely to occur and would cause illness or injury to the consumer.”

These include biological hazards such as bacteria and viruses. At Washington Crab Company in Washington, owner Jimmy Johnson says they pay particular attention to the pasteurization process.

“If you don’t get the crabmeat pasteurized properly, you don’t kill the bacteria,” says Johnson, chairman of the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission.

Plants also must watch for chemical hazards such as histamine, which is produced naturally by bacteria on certain fish and can cause severe allergic reactions in some people. Physical hazards include metal fragments.

Businesses must then find ways to manage hazards through “critical control points.” To keep bacteria from producing histamine in fish, for example, seafood is stored on ice at or below 40 degrees.

Under the rules, crab processors must record the time and temperature at which each batch of crabs is cooked and monitor their coolers at least twice daily.

To help seafood companies with their cooking operations, the NC State Seafood Lab has conducted validation tests at 15 facilities.

“We conduct temperature distribution profiles to determine if the cooking schedule is adequate to eliminate harmful bacteria,” says Dave Green, director of the lab and a North Carolina Sea Grant researcher. “We found all plants met the minimum requirements, but in many cases, greater efficiency could be achieved with simple changes in procedures.”

Under HACCP, companies must write and follow basic sanitation standards, including using safe water in food preparation and cleanliness of food surface contacts.

How is the new program working?

“We are satisfied that people are complying with HACCP,” says Reardon. “The most common violation is record keeping. Most of the problems are around the maintenance of records.”

Dealers and processors often complain about the extra paperwork. Although Henries of Carolina Seafood supports the basic principles of HACCP, he says the “paperwork is a nightmare.”

Johnson agrees and says the program has added another layer to the bureaucracy. “HACCP doesn’t address where the problems have historically occurred — during transportation or at home after the product is purchased.”

Because of the HACCP plan, Johnson hired two additional workers. “However, there has been no increase in the price that we get for the crabmeat,” he says.

SEAFOOD SAFETY WORKSHOPS

Since the seafood safety program came into effect, North Carolina Sea Grant and the N.C. Cooperative Extension Service have offered HACCP training workshops. The FDA requires HACCP certification for seafood dealers and processors when designing a HACCP plan and reviewing records.

“We have trained about 400 workers at 12 workshops,” says Nash.

This summer, North Carolina Sea Grant and the Extension Service will be offering new sanitation control workshops. At the one-day workshop, industry workers will draft sanitation standard operating procedures and develop monitoring programs for FDA’s key sanitary conditions, including rodent control and clean water.

After seafood is processed, it is handled by a number of people, including restaurant workers.

To educate restaurant workers about seafood safety, North Carolina extension agents Jean Rawls and Sandra Maddox initiated a restaurant safety course. With funding from a N.C. Fishery Resource Grant, the agents developed a video, handbook and workshop for restaurant workers.

The course, which covers all types of seafood and every stage of handling — from inspection upon arrival to serving — arose from the increasing concern about the potential for a public health problem in the growing coastal area. “We have a lot of seafood restaurants in our area,” Rawls says.

Restaurants, which are inspected by county health departments, typically employ many young people, perhaps newly graduated from high school, with minimal background in food service and little knowledge of the biological threats to food safety.

“This is for people who don’t have that technical experience,” she adds.

Between HACCP and food safety training for restaurant workers, Nash says that consumers should not have any concerns about eating seafood.

“North Carolina processors have a long history of providing safe seafood to their customers,” he says. “HACCP and the restaurant food safety training initiatives will ensure that North Carolina remains a source of wholesome seafood and seafood products for both wholesale and retail buyers.”

This article was published in the Early Summer 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: