Ship Ashore! Risk and the Historic U.S. Life-Saving Service

Haunting tales of doomed vessels and heroic rescues of shipwrecked sailors along North Carolina’s coast are the stuff of lore and legend. And so are the lifesaving stations and crews that kept watch on the Graveyard of the Atlantic over the past 140 years.

Vivid accounts of surfmen plucking sailors and ship passengers from terrifying storms have long captured the attention of historians and the imagination of sailors and landlubbers. The image of a surfman in a rain hat, suit and boots has become a near mythical figure — “an angel dressed in oilskins” and “a saint in a sou’wester” to quote one poet.

While the focus on famous wrecks and rescues enlivens the region’s history, an East Carolina University researcher says it often overshadows other activities of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, the forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard. Joshua Marano, a graduate student in the ECU Program in Maritime Studies, says day-to-day activities of the service and lesser-known wrecks are important parts of the maritime heritage of the Outer Banks.

“I think a lot of North Carolinians are sometimes jaded because they feel their history can’t be told by a handful of famous wrecks,” says Marano, who also is a second class boatswain’s mate in the Coast Guard Reserve.

Marano, who received a fellowship from North Carolina Sea Grant to support his research, is studying the role of risk management in the development of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, as well as the service’s effect on shipwreck patterns along the Outer Banks.

His project examines the establishment, funding and maintenance of the life-saving service, which built 29 stations in North Carolina. He also compiled detailed information on numerous wrecks, including the weather, location and reported loss of life.

EVALUATING TRENDS

According to Marano, previous research on the life-saving service tends to focus on the design of life-saving apparatus, individual wrecks, station construction, or the heroic acts of individual men or crews, while neglecting the service’s overall influence or trends.

Nathan Richards, a faculty member in ECU’s Program in Maritime Studies, says Marano’s project tells what happened “before those men jumped on the boat and rode off.” It’s significant, he says, because it highlights how the crews came to be on the beaches and how people learned to deal with challenging conditions and expectations.

Essentially, Marano is applying several sociocultural theories about risk to historical events. He wants to consider whether the life-saving service was proactive or reactive in response to wrecks and the effect of some major shipwrecks on the service. He’s still analyzing data and has not made final conclusions.

However, preliminary work already provides some clues to how mariners looked to the stations on the Outer Banks for navigation guidance, as well as rescue. He cites one incident, the wreck of the steamship Metropolis in January 1878, in which a captain intentionally beached his sinking ship on an Outer Banks shore because a life station was nearby.

OCEANFRONT SHIPWRECKS

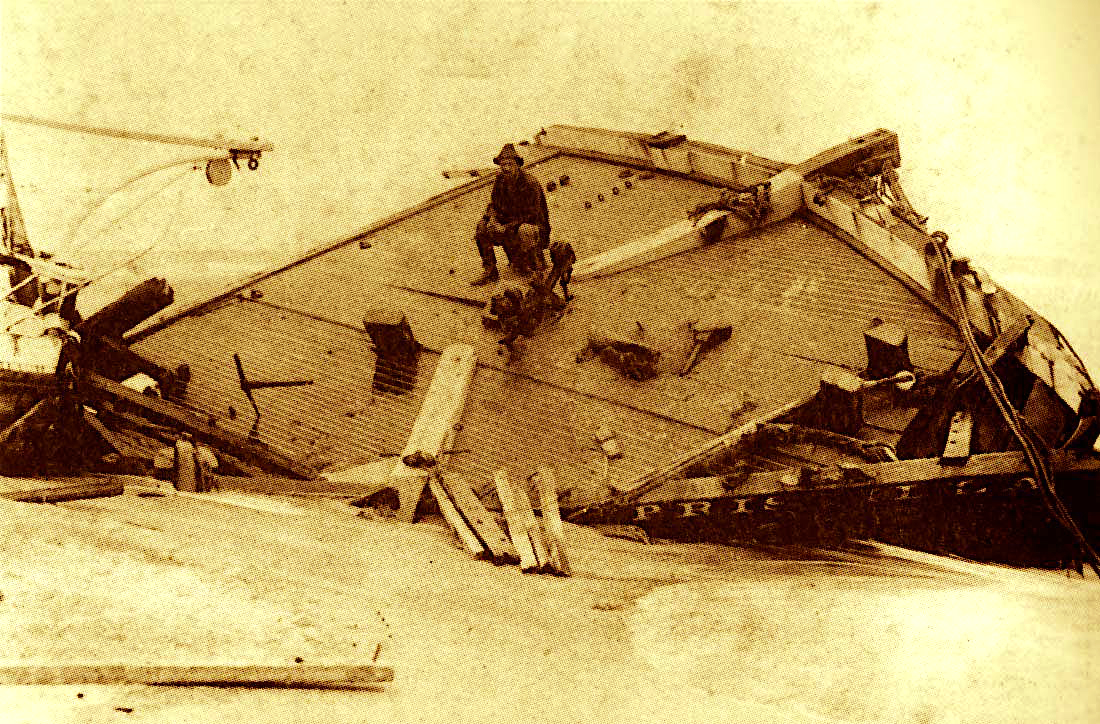

Being shipwrecked close to shore was often as perilous as sinking at sea before surfmen at government life-saving stations began keeping watch. Historical accounts say many sailors and ship passengers perished in treacherous waters while trying to swim to the relative safety of a beach that was often only a few hundred yards away.

The federal government’s assistance to mariners focused on vessel inspections and aids to navigation until 1848 when Congress authorized funds for some life-saving efforts. The initial program, part of the U.S. Treasury Revenue Marine Bureau, provided buildings, equipment and volunteer crews along the New Jersey coast. But the effort was considered unreliable and disasters spurred calls for improvement.

According to the U.S. Life-Saving Service Living History Association, the volunteer service ended in 1871 when Summer I. Kimball was appointed to head the marine agency. Under his leadership, stations were added and crews became more proficient and professional. In 1874, the station network expanded to Maine and to 10 locations south of Cape Henry, Va., including North Carolina. The first seven life-saving stations in North Carolina went from present day Currituck to Little Kinnakeet, now within Avon just north of Cape Hatteras. Each station was staffed with a year-round keeper and up to six surfmen employed during storm season and on call at other times. In 1915, the U.S. Revenue Cutter System and the U.S. Life-Saving Service were combined to create the Coast Guard.

While North Carolina was not the first to receive life-saving stations, two disastrous shipwrecks about two months apart helped shape the service. The USS Huron was only 200 yards off the beach at Nags Head when it ran aground during a storm in November 1877. Faced with heavy surf, cold temperatures and strong currents, most of the crew tried to remain on the ship until help arrived — but nearby life stations were closed until December. One large wave swept a dozen men away at one time, according to historical records. A total of 98 eventually died.

Two months later the steamship Metropolis ran aground 23 miles to the north with the loss of 85 lives. Public criticism prompted Congress to fund the construction of additional life-saving stations on the coast and to increase their months of operation.

COASTAL PATROLS

In the early 1870s, life-saving stations on the Outer Banks were 10 to 15 miles apart. Crew members regularly watched for ships in distress by sending out a patrol, one from each station. The men met halfway, then walked back. The problem, Marano says, was that if a vessel wrecked after a patrol left the midway point, it wouldn’t be spotted for several hours.

As the service grew, stations were built about five miles apart. If a ship had to run aground, there was always a station within sight. “They would be able to wreck, knowing that on that particular stretch of coast there would be a life-saving station every five or six miles,” Marano says.

Stations eventually developed the capability to communicate with vessels at sea with international symbols. Marano found several incidences in which vessels pulled into sight of a station to obtain information on weather and location. Ships used the stations as reference points for navigation and communication. First the telegraph, and later telephones, allowed stations to communicate directly with each other and to keep tabs on ships navigating along the coast.

After 1879, the location of life-saving stations was placed on maps. The service also began publishing pamphlets that illustrated the capabilities of the stations and provided advice about what sailors and passengers should do in an emergency to assist rescue. For example, Marano says, those on a stricken ship were told to shoot a flare or signal of some kind and, most importantly, remain on the wreck.

Marano limited the scope of his study to a 30-mile stretch of the Outer Banks — 15 miles north and south of Oregon Inlet. That area included six stations: Nags Head, Oregon Inlet and Chicamacomico, all established in 1874; Bodie Island and Pea Island in 1878; and New Inlet in 1882.

The area now includes popular beach communities and part of federally owned land in the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge and Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Though relatively small, it accounted for 134 shipwrecks in 40 years. “That’s only along the beaches,” Marano points out. “Imagine all the vessels lost off the sight of land.”

That stretch of northern coastline was home to some of the state’s oldest life-saving stations, five of which were established within the first four years of the service. The Outer Banks is ideal for study, he says, because the area had among the longest interaction with the maritime industry and general public.

Marano also focused on the 30-mile stretch because it was relatively benign, with shoals that extended a mile or two offshore.

“It’s dangerous but it’s not quote-unquote a ship trap,” he says. The Atlantic off the North Carolina coast was known for shoals around Cape Hatteras (Diamond Shoals), Cape Lookout (Lookout Shoals) and Cape Fear (Frying Pan Shoals). All vessels had to navigate these areas while passing near the North Carolina coast. “There was no choice in the matter,” Marano says.

In contrast, his study area had dangerous shoals, but conditions were relatively safe as long as a vessel maintained a certain distance from shore — usually five to seven miles. “In other words, sailing in that area should be — while I never utilize this term when underway — routine as long as you maintain your distance from shore,” he explains. Most of the wrecks he examined occurred within a mile or less of shore, indicating there may have been some choice in navigating that close.

Marano culled data from many places, including the archives at ECU’s Joyner and Ruppe libraries, the N.C. State Archives, the N.C. Underwater Archaeology Branch, the Outer Banks History Center, the National Archives in multiple locations, and the Coast Guard Historian’s Office. He pored over the service’s annual reports, which recount activities of the agency and the individual stations, including information about payroll, repair and maintenance of equipment, and specific wrecks.

The reports — what he calls “untapped resources” for researchers — reveal the exact cause of wrecks, including whether ships ran aground in storms, by accident or intentionally. “It’s very interesting to see how much human error plays into it and how much individual decision making goes into it,” he says.

Reading government documents and deciphering scribbled handwriting may sound tedious, but Marano found insights into the people who staffed the stations and walked the beaches. For example, he recounts a report which described an argument at a station after a crew member used government-owned horses to visit his family. The crewman got into a fistfight with his colleagues and was later discharged. Marano says the vignette may not be directly related to his research but it humanizes the accounts.

LESSER-KNOWN WRECKS

There has been plenty of attention paid to famous offshore wrecks such as German U-boats, the Civil War gunboat the USS Monitor and the shipwreck near Beaufort now identified to be the pirate Blackbeard’s flagship, the Queen Anne’s Revenge.

But Marano also found reports on the loss of small fishing boats and schooners in which one or two people died. Those incidents didn’t receive headlines at the time and people don’t pay much attention to them now. Yet they are important, he says, because the victims were local fathers or sons, and a ship’s cargo — or the salvage from the wreck — may have provided lumber for houses, churches or schools.

The way the lifesaving service contributed to every life is also worthy of more appreciation, according to Marano.

He points out that crews helped the Wright brothers when they came to the coast for their flying experiments.

James Charlet, manager of the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station Historic Site and Museum at Rodanthe, welcomes additional information about the day-to-day contributions of Outer Banks life savers. He wants the public to understand how much the stations contributed to local communities and the nation’s maritime culture.

Chicamacomico (pronounced chik-ama- COM -I-co) or Chicamacomico Banks was the name commonly given to Pea Island on the Outer Banks, according to The North Carolina Gazetteer by William S. Powell. He wrote that a portion of the word is believed to be derived from an Algonquian word for “sinking down sand.”

The Chicamacomico site contains two of the 285 U.S. Life-Saving Stations built from 1848 to 1914. It was the first operational station in North Carolina and is located on the state’s easternmost point. The 1874 Station, opened in December 1874, was located approximately half a mile north of its current location, but was relocated soon after a new station was built in 1911. Once the replacement station was built, the 1874 Station was used as a boathouse and storage shed.

The station was decommissioned and closed in 1954. It was abandoned until it was acquired by a private citizen, who turned the property over to the residents in the Hatteras Island communities of Rodanthe, Waves and Salvo. They created the nonprofit Chicamacomico Historical Association.

Charlet says Chicamacomico was the scene of the most highly awarded maritime rescue in American history — the SS Mirlo, on Aug. 16, 1918. Surfboat No. 1046 used in the rescue is on display The complex includes two station buildings and several outbuildings. It is considered the most complete collection of remaining life-saving stations in the nation.

Charlet says most visitors at the restored life-saving station and museum have the notion that surfmen served as beach lifeguards or emergency medical personnel who only responded to ships in distress.

“That’s far from the truth,” he says, noting that station crew members had highly regimented schedules they followed six days a week. They practiced life-saving techniques constantly, he adds, and worked to keep equipment in working order in harsh, corrosive conditions.

Charlet agrees with Marano that the stations were integral parts of the isolated Outer Banks communities. They often were the “welcome centers of their day,” he says, and the places where travelers went for information and assistance on land, as well as water.

He also says many of the contributions are overlooked, a situation the historic site addresses with an annual American Heroes Day every August that highlights activities of the Life-Saving Service and Coast Guard. The ceremony includes recounting historic rescues and demonstrating search-and-rescue techniques.

In the summer, Coast Guard members at Chicamacomico conduct the full beach apparatus drill every week.

IDENTIFYING WRECKS

Marano says his research has practical archaeological applications because it could help describe shipwrecks for which only general information is known. For example, a report on the Strathairly that sank near the Chicamacomico station in 1891 told how far the wreck occurred from the station and how far offshore. Because the wreck had a high loss of life, the station keeper went out several weeks after the incident and measured the exact distance. By using maps of the shoreline from that time, Marano could pinpoint the location.

Some wreck sites may be known to recreational divers, fishermen and local residents by informal names such as the “oyster wreck” because of abundant oysters at the site or the “boiler wreck” because a ship’s boiler stands out. But Marano says his research and methods could provide the history of a particular wreck.

“Connecting a wreck on the bottom with the people who sailed it is a lot of what we do.”

A Fayetteville native, Marano, 24, received a Bachelor of Arts degree in history with a minor in coastal studies from ECU. He grew up with an interest in maritime history. He joined the Coast Guard to gain direct maritime experience. He is assigned to the Coast Guard Station at Wrightsville Beach where he is a boat crew member with duties that include running boats and assisting in law enforcement and search-and-rescue missions.

His rescues now are more likely to involve swimmers swept out to sea. “It’s not necessarily a vessel sinking as it was back in the day,” Marano says.

A workshop that may also be of interest: NCCAT Legacy Seminar: U.S. Coast Guard: Guardians of the Sea: May 7-11.

This article was published in the Winter 2012 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: