Safeguarding Water

Legislative Gaps and Innovative Solutions

A new approach to watershed health protects the Falls Lake drinking water supply for 500,000 North Carolina residents.

On a Sunday morning in June 1969, in Cleveland, Ohio, the Cuyahoga River was burning — again. It wasn’t the first, second, or even third time this had happened for the heavily industrialized waterway, which snakes and weaves through northern Ohio before pouring into Lake Erie.

This was at least the dozenth fire on the Cuyahoga.

Today, the river has become a familiar anecdote when discussing the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the passage of 1972’s Clean Water Act (CWA). The fires’ role in creating these agencies is more complicated than simple cause and effect, but the river nevertheless became both a symbol of industrial pollution and a common rallying call to action.

Over 50 years old now, the CWA established a framework for controlling the release of pollutants into the nation’s waters from a “point source” — “any single identifiable source of pollution,” according to the EPA, such as a factory or wastewater facility.

Non-point source pollutants are more diffuse and difficult to trace, such as runoff from development, agricultural areas, and roads, as well as from unmanaged regions, such as forests. Both point-source and non-point source pollution can lead to an excess of nutrients, notably nitrogen and phosphorus, in waterways.

While nutrients are naturally occurring and necessary, high quantities can be problematic, causing an overgrowth of algae and increased algal toxins, as well as unsafe waters for consumption or recreation, leading to closures and advisories.

The Sackett v. EPA decision in 2023 reduced the CWA’s jurisdiction over wetlands nationwide. However, even terrain under its safeguard may not be protected enough from pollutants from unmanaged lands. Researchers from the University of Georgia concluded that CWA policies do not reduce nutrient pollution sufficiently to meet the water quality goals the CWA outlines. The study notes up to 58% of stream and river miles in the U.S. are in poor condition due to excess phosphorus and 43% due to excess nitrogen.

In addition, according to the EPA, many states report non-point source pollution as a leading concern for water quality problems.

But how do we control pollutants from non-point sources and unmanaged lands?

The recent efforts of the Upper Neuse River Basin Association (UNRBA) to update the Falls Lake watershed regulations have revealed some innovative solutions. The UNRBA offers a new framework for addressing challenging state and federal regulations.

Falls Lake: A Case Study

In 1965, Congress authorized the construction of the Falls Lake Reservoir project as part of the Flood Control Act to mitigate flooding from the Neuse River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed and filled Falls Lake Reservoir in the late 1970s and early 1980s by blockading the river at a natural fall line.

Once they completed the dam in 1981, the resulting “Falls Lake” — named after the “Falls of the Neuse,” where the dam was constructed — was congressionally authorized to act as flood control for downstream communities, as well as a drinking water supply, recreational area, and habitat for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife.

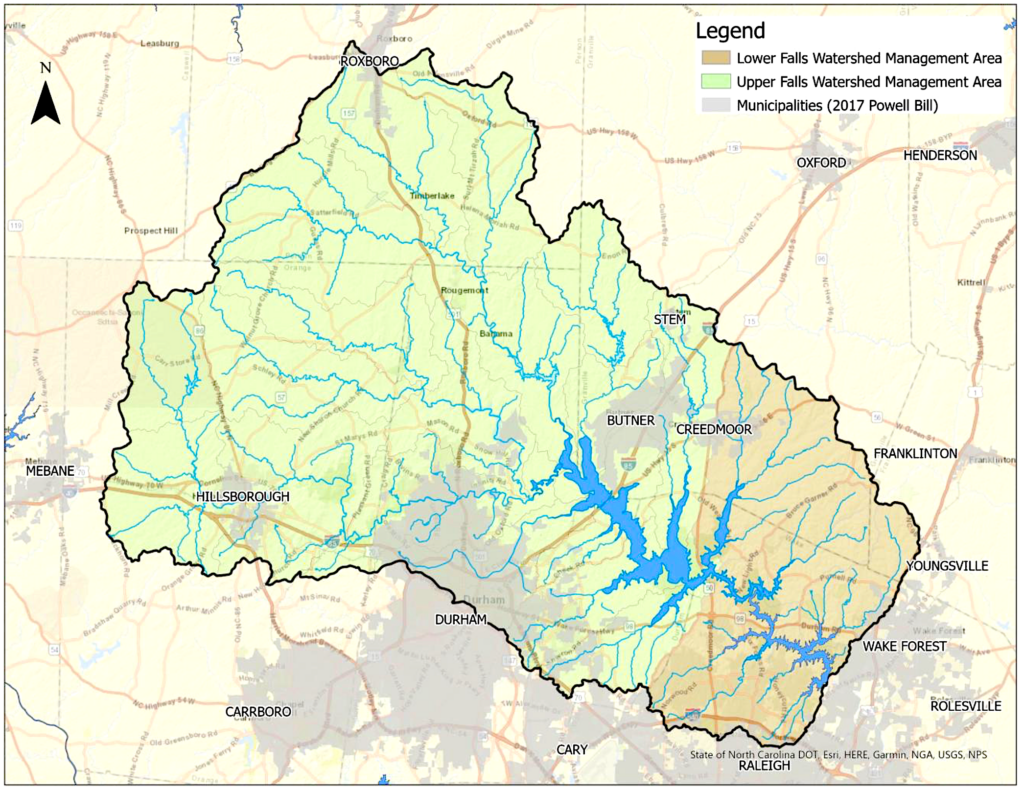

Today, Falls Lake serves as the source of drinking water for over 500,000 North Carolinians, processing 41 million gallons per day. Falls Lake receives water from the Upper Neuse River watershed, a 770-squaremile region across Orange, Person, Durham, Granville, Wake, and Franklin counties.

“The watershed provides the majority of Raleigh’s drinking water supply,” says Jane Harrison, North Carolina Sea Grant’s economics specialist and a UNRBA board member. “We’re very much invested in how we balance development with environmental needs and ensure that we have a clean and ample drinking water supply into the future.”

However, Harrison says, managing the watershed’s health is complicated. Because a riverine environment was converted to a lake, water that once moved quickly through the area remains there longer. As a result, the water has more time to accumulate phosphorus and nitrogen, contributing to “eutrophication” — when nutrient levels are excessive — as well as high levels of chlorophyll-a (an indicator of algal growth).

“Some nutrient load requirements are difficult to meet in Falls Lake, including those for nitrogen and phosphorus,” Harrison says. “There have already been great efforts to reduce nutrients by using prohibitions on development and by technological means, like advanced wastewater treatment. But it’s not enough.”

Rules and Recommendations for the Reservoir

According to the NC Department of Environmental Quality, rules and regulations require that “all major sources of nutrients in the watershed reduce their nitrogen loads by 40% and phosphorus loads by 77%” by 2041.

However, major sources of nutrients are non-point source pollutants, primarily from unmanaged lands. Over 70% of the Falls Lake watershed consists of unmanaged land, including forests, wetlands, and undeveloped areas, and more than half of the nutrient load in Falls Lake originates from these areas alone.

Despite ongoing efforts, Harrison adds, given the nature of Falls Lake, it was always unlikely it would meet state standards for water quality. A decade of research studies has indicated that even drastic measures won’t be sufficient. Yet, over the last ten years, the UNRBA has set goals that incentivize neighboring municipalities and counties to proactively protect the watershed.

UNRBA recommendations primarily focus on conserving forests and unmanaged lands, restoring stream and wetland buffers, expanding the floodplain, conducting controlled burns, limiting development, and promoting projects focusing on water quality throughout the watershed.

In particular, the UNRBA asks jurisdictions surrounding Falls Lake to make land preservation and restoration investments to protect the drinking water supply. In 2023, the City of Raleigh made one such investment, allocating $3.7 million to preserve 406 acres in the watershed into perpetuity.

UNRBA board members include representatives from each municipality and county that surrounds Falls Lake — urban areas like Raleigh and Durham to smaller towns like Rolesville and Butner. They emphasize the need for a holistic management strategy to improve the health of the entire watershed system by addressing interactions among surface waters, land surfaces, groundwater, soils, and atmospheric and climatological drivers, instead of focusing solely on point or non-point sources of nutrient loading.

What I see as the best way to preserve this watershed is through preservation of land rather than extremely expensive wastewater treatment technologies,” says Harrison. “Reducing erosion and runoff — intercepting the nutrients before they enter the water — instead of trying to reduce total nutrient levels around Falls Lake is more cost-effective.”

The UNRBA recommends that current levels of chlorophyll-a, which exceed the standard in parts of the lake, have not impacted water treatability, led to fish kills, or increased algal scum. The association also notes that current state standards cannot be achieved for Falls Lake. It will always be eutrophic.

This has implications for drinking water. Last spring, Raleigh residents reported to WRAL that their tap water had a strange smell and taste, which experts linked to an algal bloom in the lake.

“There is a seasonal taste issue for Raleigh water,” explains Harrison, who recommends contacting the city if concerned. “But they test every single day and ensure that it’s safe to drink.”

Cross-County Collaboration and Connectedness

The N.C. Division of Water Resources is now evaluating UNRBAs recommendations for Falls Lake.

“These new rules that the UNRBA board wants to get adopted are based on research,” says Harrison. “We’re looking at the data and saying, ‘Okay, this is what we’re seeing to be effective.’”

She adds that monitoring the watershed’s health is still ongoing. “When you have unstable banks and erosive soil, higher levels of nutrients enter Falls Lake. Those are the kinds of hotspots our studies have identified. Now we know where to prioritize bank stabilization and restoration efforts.”

Harrison says that maintaining forested areas is vital to watershed health. Raleigh’s land use rules limit development around Falls Lake, and she says such cross-county collaboration is essential.

“We want to model some of the best policy that we can so that other upstream municipalities, like Durham, are more willing to protect Falls Lake, even though they don’t drink its water,” Harrison says. “We’re all connected in this.”

Although careful management of nutrient pollution in Falls Lake clearly brings a much different set of challenges than those associated with Ohio’s fire-prone Cuyahoga River, it also offers a potentially wide range of benefits.

“If we can continue to have a high-quality water source and not have to spend unnecessary funds to protect it, that’ll keep our public water utility costs low,” explains Harrison. “Our taxes will be lower, our water bills will be lower. Watershed protection makes this area a more affordable place to live.”

And, Harrison adds, if we invest in and maintain land around the Falls Lake watershed, we are accomplishing much more than protecting a critical supply of drinking water.

“We’re also providing wildlife habitat,” she says. “We’re creating opportunities for recreation. We’re maintaining our unique ecology and connecting local communities to what’s special about the Piedmont.”

More

EPA Guide on Nonpoint Source Pollution

NCDEQ on the Falls Lake nutrient strategy

“What’s Wrong with Raleigh Tap Water? Algae Bloom at Falls Lake Behind the Smell, Color”

National Park Service on the 1969 Cuyahoga River Fire

Marlo Chapman is a communications specialist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and former contributing editor for Coastwatch. Her writing also has appeared in American Scientist.

lead photo: CelticStudio/AdobeStock

- Categories: