Tracking Snowbirds: Communities Consider Economic Boom from Boaters

By Emily White

Posted June 24, 2016

Not all snowbirds traveling the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway have feathers. In fact, some have boats.

North Carolina Sea Grant-funded researchers from East Carolina University conducted a study to learn more about the transient boaters who use the waterway, commonly called the ICW. These boaters follow warm weather, whether it be northward in summer or southward in winter, as the seasons change.

“The project primarily tells us what methods will work best in future research, but it also gave us some preliminary information about the boaters’ behaviors. We also took a look at how much the communities really want to attract these boaters and why,” says Hans Vogelsong, a researcher in recreation and leisure studies at ECU who led the project. “This research could really help communities direct resources to where boaters, the consumers, want them.”

His team found that there may be financial incentive for communities adjacent to the ICW to pour resources into low-cost docking, fuel at those docks and grocery stores.

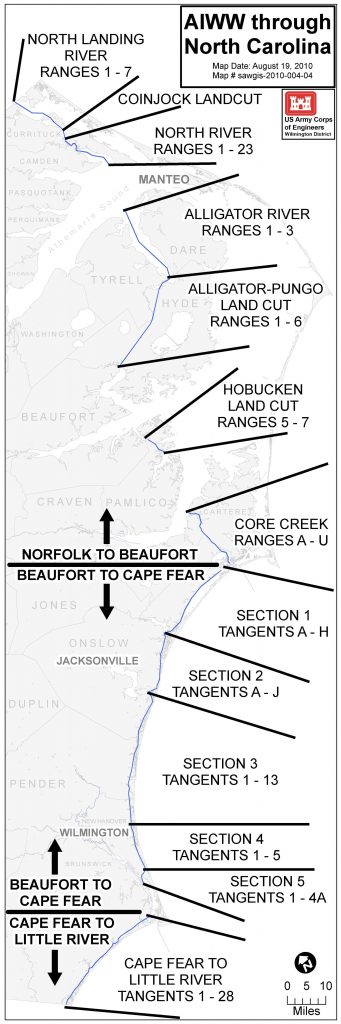

Though there are other waterways commonly referred to as the ICW, each one covers a particular area. The research team focused their study on the Atlantic ICW, which stretches 1,200 miles from Norfolk, Virginia, to Key West, Florida, and draws both for-work and for-pleasure boaters.

According to the study, travelers passing through North Carolina spend an average of $4,410 on their entire trip along the ICW and about $286 in communities close to the waterway. The captain of the ship tends to do the bulk of this spending. The vessels carry about three people.

In North Carolina, approximately 2,500 transient boats travel through the state via the ICW during migrations. Each boat spends about five days on the North Carolina portion.

The researchers surveyed ICW boaters to provide insight into spending habits, what kind of goods and services would draw them from their boats to communities inland, and how far away they would be willing to go from their floating homes.

The ECU team also asked leaders in adjacent communities how important those transient boaters were to their local economies.

As a pilot program to examine the most effective methods of gathering ICW traveler-related data, the study revealed some trends in boaters’ behaviors that may help businesses adjacent to the ICW attract more customers.

Some of the big draws for ICW boaters to meander inland include access to free or low-cost docking, fuel at docks, grocery stores, deep-water dock access and fine dining. The boaters didn’t care much about hotels being nearby, but wanted everything else to be near the docks.

“Communities adjacent to the ICW could benefit by providing these amenities and ensuring that they are within walking distance of the waterway. Promotional efforts online or at various locations along the ICW could draw these visitors,” says Jack Thigpen, Sea Grant extension director.

The research team hopes to use the same methods on a larger study in the future.

Liz Brown-Pickren shares her experiences conducting surveys for this project.

Emily White, a senior at NC State University, is a communications intern with North Carolina Sea Grant.

- Categories: