Integrating engineered solutions — exploring the relationships between nutrient overload, water quality, and ecosystem health — helps to maintain coastal resilience and protect local economies.

For any beach lover, a crystal-clear waterbody is a sublime sight. Water quality directly affects ecosystem health, biodiversity, and the human communities that rely on these waters for food, recreation, and livelihoods.

Clean water also supports the activities of coastal ecosystems, such as estuaries, marshes, and coral reefs, which act as natural barriers against erosion and extreme weather. Moreover, high water quality is essential for the survival of marine species and prevents algal blooms and hypoxic conditions that can harm aquatic life and, in turn, damage local economies.

Excess nutrients like nitrogen, in particular, while essential for plant and animal growth, can significantly harm aquatic ecosystems. Nitrogen promotes the rapid growth of aquatic plants and algae, leading to algal blooms. These blooms block sunlight, disrupt underwater ecosystems, and consume dissolved oxygen during decomposition, creating an imbalance that can harm fish and other aquatic life.

This process, known as “eutrophication,” can degrade water quality, causing an unpleasant layer of algae on the water surface, and even lead to fish kills, reducing biodiversity. Such nutrient overload also makes activities like fishing, swimming, and boating less enjoyable.

Addressing these challenges requires careful nutrient management to protect intertwined ecosystems and human interests.

Anne Smiley, a postdoctoral research associate at the Institute for the Environment at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and her colleagues — Suzanne Thompson, Nathan Hall, and Michael Piehler — studied how storm characteristics influence nitrogen removal in New Bern from 2017 to 2019, in order to better understand how to sustain water quality.

Stormwater, Urbanization, and Excess Nitrogen

The City of New Bern, located in a flood-prone region of North Carolina, faces challenges with nutrient runoff and nitrogen loading, which were highlighted during Hurricane Florence in 2018. Smiley, a winning member of North Carolina Sea Grant’s first Coastal Resilience Team Competition, says that New Bern was the perfect place for the study as it is “a mosaic of both developed and natural landscapes.” She and her colleagues directly measured nitrogen removal across various ecosystems, exploring the role of natural habitats in modifying nutrient pollution and supporting water quality.

“Storms bring in extra nitrogen to the system when rain falls on the landscape both on-site and upstream within the watershed,” says Smiley. “That stormwater mobilizes nitrogen that is stuck on land and delivers it to the receiving waterway. When we have a lot of rain, there is a lot of water flowing down river.”

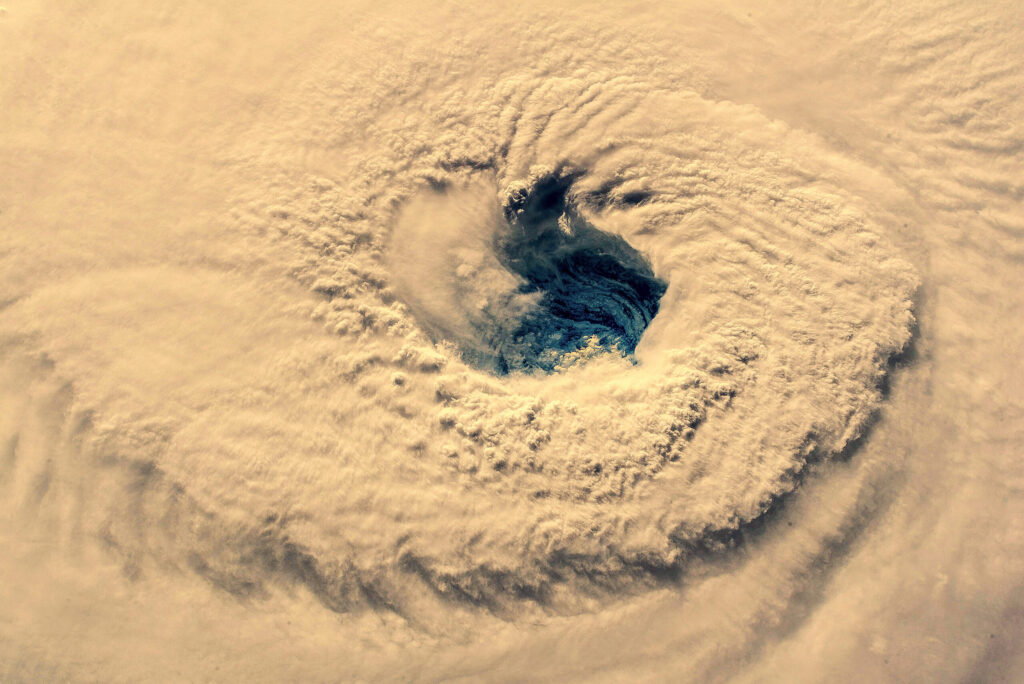

Climate change further challenges estuarine systems’ ability to remove nitrogen. Some models predict an increase in the most intense storms and up to a 20% increase in precipitation rates by 2100, according to a news brief from NASA.

The increased storm intensity and frequency can lead to higher nutrient loads in shorter periods, stressing these environments and impacting water quality, marine life, and overall ecosystem health, with urban areas particularly susceptible.

“Urbanization changes the composition of the landscape,” says Smiley. “Where there used to be forests and wetlands, there are now neighborhoods and parking lots.”

According to Smiley, humans tend to add a lot of nitrogen to the marine ecosystem in the form of residential fertilizers, household cleaners, and pet waste.

In addition, highways and stormwater pipes, although necessary, concentrate and expedite the flow of stormwater eventually into estuaries, bypassing forests and soils that could soak up both water and nutrients.

Recommendations

Planning for the expansion of urban areas in a way that does not degrade the environment seems like a herculean task, especially in coastal regions experiencing urbanization and precipitation events disproportionately. Smiley says findings from her study can inform land use policies, sustainable development practices, and stormwater regulations to maximize water quality benefits. Urban habitats like lawns and grasses, she adds, are surprisingly effective nitrogen removers.

“I think our first line of defense is preserving the valuable natural environments,” she says. “The second involves strategic development to preserve some section of the land as open space and constructing new stormwater ponds so that they are connected to some natural body of water.”

She sees engineering and restoration as a third line of defense, such as “adding fountains or some kind of apparatus to artificially circulate the water in existing stormwater ponds, to ensure even oxygen and nutrient distribution. We also can focus on restoring stormwater wetlands and natural vegetation.”

Smiley’s research also links nitrogen removal to its economic value.

“North Carolina’s Nutrient Offset Program puts a region-specific dollar amount on each kilogram of nitrogen removed,” Smiley says. “So we can actually quantify its value, which is helpful when trying to justify and plan conservation and restoration projects.”

For coastal areas facing the pressures of urbanization and climate change, sustaining water quality involves managing runoff, reducing pollution, and implementing policies for sustainable development.

“I think people are drawn to the coast hence populations are growing disproportionately in coastal areas,” Smiley says. “Ensuring effective water quality management can enhance coastal resilience by making these ecosystems more capable of adapting to environmental changes and safeguarding resources essential to both local ecosystems and human communities.”

the full study

Storm Characteristics Influence Nitrogen Removal in an Urban Estuarine Environment

More

Climate Resilience: Natural Landscapes and Flood Mitigation in New Bern

Resilience and Redevelopment in Duffyfield

The Guide to Coastal Living: Storm Readiness and Recovery

Emma Davies is an award-winning journalist and a contributing editor for Coastwatch. She is pursuing a masters of arts in liberal studies at North Carolina State University, with a major in communication and a minor concentration in genetic engineering and society.

- Categories: