“If you don’t let us fish in peace, the Attorney General’s office and the News & Observer will soon learn there is a private North Carolina ocean beach not open to the public.”

Came the news that a man in the business of purveying surfboards and such could not easily, legally get to the North Carolina surf because no public access walks existed anywhere along the twelve miles of Currituck County seabeach known as Duck. The town of Duck threw up its municipal hands, not knowing how to fix the problem — for all the oceanfront there had been privately developed before the town incorporated, an official said.

And regularly comes further news that, in beach towns where state-directed public beach access points do exist, sufficient car-parking for folks to make use of them often does not.

A far cry from when I was a boy, when families walked onto the seabeaches across empty lots, open sand near fishing piers (and there were many).

The beaches belong and have always belonged to the people of North Carolina, in public trust — that is, the area below the mean high-tide line. Getting across the privately held dry sand above the wet sand and the narrow line and scurf the high tides have left, there was the rub of the old have and have-not brush.

And there have also been times when, even though the beach may have been approached from the ocean, the people’s right has been challenged, at times abridged.

A case in point:

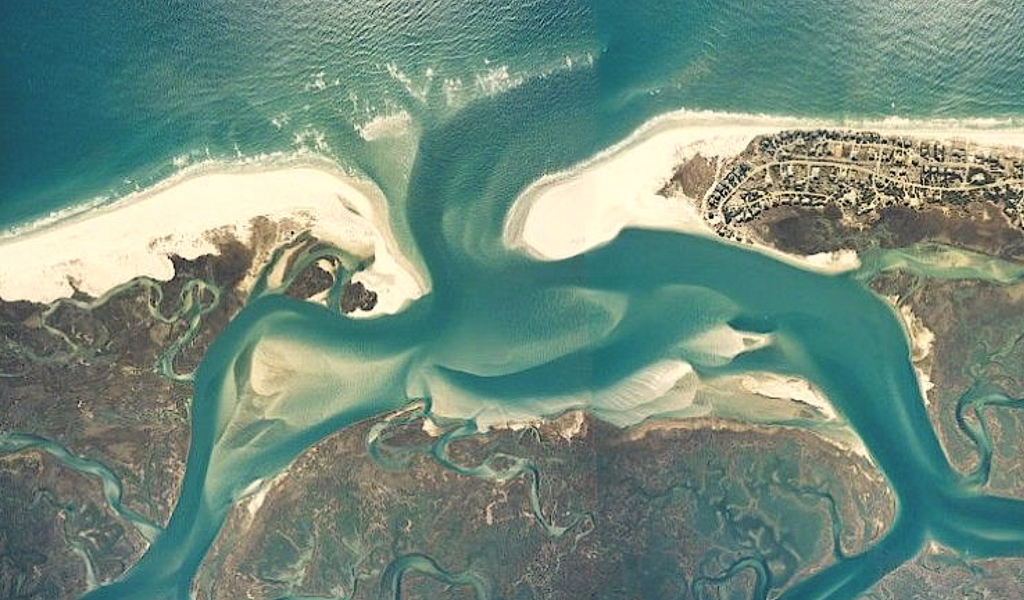

The inveterate master-fisherman and naturalist Tom Earnhardt once came around from the great mile-wide marshes between the Intracoastal Waterway and the sea, and motored through Rich Inlet into the ocean waters in his skiff, following a school of Spanish mackerel after bait-fish. When the Spanish moved close in to shore, into the light morning surf, Tom and an angling friend hopped out of the boat and pursued the mackerel on foot in the surf not far from the boat.

In no time at all, he saw out of the corner of his eye an animated man running his way, urgently waving his arms.

“You have to leave, you have to go!” said the man. “This is private beach. You can’t be here!”

“I’m just fishing, following some Spanish,” Tom said. “I won’t be here long.”

“You can’t be here at all,” the man said. “This is privately-owned beach. You have to leave now.”

“No, sir, I don’t,” said Tom.

“Yes, you do — leave now!”

Tom Earnhardt, one of the first attorneys for the environment the State of North Carolina ever hired, back under Attorney General Robert Morgan, has always been a genial man, slow to anger but very quick to respond to the unfair, the out-of-bounds, the illegal, as he did now, saying:

“Sir, I am an attorney, I have worked in the Attorney General’s office, and I know the law. This beach is public — publicly owned — up to the high-tide mark. I am disturbing no one, and I will not be here long.”

And then he went back to fishing.

“You’d better not be here when I get back,” said the man.

“Can’t say that I won’t be,” Tom said calmly, over his shoulder.

When the man returned, he brought along a bigger, bruter fellow.

With a holstered pistol on his hip.

“What’s the problem here?” he said. “You’ve been told this is a private beach and you have to leave.”

Tom held his fishing rod tight and faced the two men.

“There is no problem, sir. I know what the law is, and I know that this surf belongs to the people of North Carolina. If you don’t let us fish in peace, the Attorney General’s office and the News & Observer will soon learn there is a private North Carolina ocean beach not open to the public. I don’t think you or your employers will want to read about it in the newspaper.

The man with the pistol put his right hand upon his holster but made no other move.

“I plan to be here fishing these Spanish for a few more minutes,” Tom said, “and that’s all there is to it. Good day, gentlemen.”

So Tom Earnhardt and his friend went back to fishing again. The two Figure Eight gatekeepers grumbled and cussed and wandered off, muttering about repercussions, while Tom, who dislikes confrontation yet dislikes even more such bullying as privilege often puts forth, felt he had had to, once again, not simply establish but proclaim the basic right of ownership and fair use that every Carolinian, monied or not, has to every bit of our many public-trust waters and wet sand — those whose waves break upon three hundred miles of seabeach and on ten thousand miles of sound-country shorelines — in our state.

And, Tom recalled cheerfully years after his set-to, the Spanish were really biting that day.

More from Bland Simpson in Coastwatch

“This Wet and Water Loving Land”

Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals: The Mystery of the Carroll A. Deering

Two Captains from Carolina: Moses Grandy, John Newland Maffitt, and the Coming of the Civil War

Bland Simpson, North Carolina’s oft-honored voice of our state’s coast, recently taught his final class as Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the pianist for the Red Clay Ramblers, the Tony Award-winning string band, and has collaborated on such musicals as Diamond Studs, Fool Moon, Kudzu, and King Mackerel & The Blues Are Running.

- Categories: