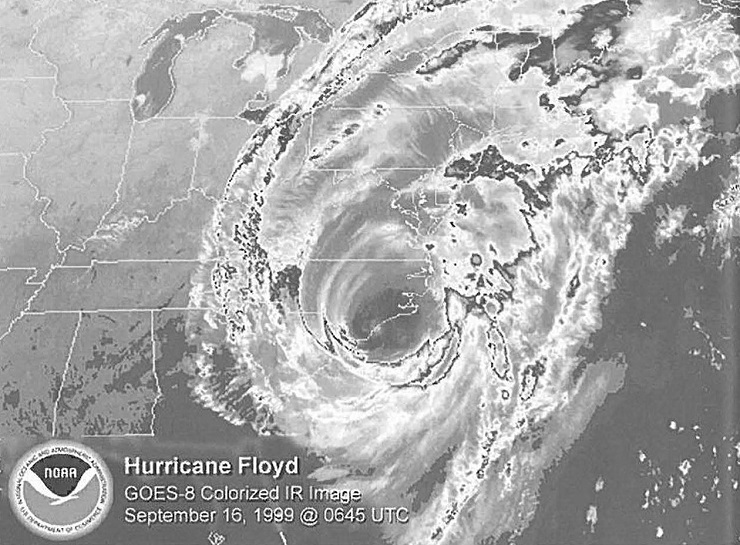

Along North Carolina’s southeastern coast, all eyes were on Hurricane Floyd on Sept. 15, 1999. And, for good reason. The monstrous storm was churning up the Atlantic with its eye fixed on the Cape Fear region. Floyd had roared through the Bahamas as a Category 4 and threatened the Florida coast as a Category 3.

Outer bands of wind and rain already were whipping across the area. Powerful waves were pounding shorelines. State and local emergency workers braced for a worst-case scenario.

In the early hours of Sept. 16, Floyd came ashore, as predicted, near the mouth of the Cape Fear River — as a Category 2 storm.

Steve Pfaff, National Weather Service (NWS) senior forecaster in Wilmington, explains that the longer the massive storm lingered near the coast, the better chance it would pull drier continental air from the Southeast United States into its circulation. This infiltration would inhibit the convection near the eye of the storm and help lessen the strength of the wind.

But no one at the NWS exhaled with relief, says Pfaff, who was on duty at the time. As a Category 2 storm, Floyd still packed winds of 80 to 120 miles per hour, excessive rainfall and powerful waves.

Peak wind gusts reported by the NWS and other sources varied: 112 mph at Frying Pan Shoals; 86 mph in Wilmington; 138 mph from a Wrightsville Beach rooftop; 130 mph at New Hanover Emergency Operations Center; and 123 mph at Topsail Beach.

Winds toppled utility poles, trees and peeled the roof off Brunswick Community Hospital. Patients were evacuated to Columbus County Hospital and New Hanover Regional Medical Center.

And, there was storm surge. According to NWS reports, the storm surge along the barrier islands from Sunset Beach to Topsail Island averaged 10 feet, with Carolina Beach’s north end marking a 13-foot surge.

By comparison, Hurricane Hazel pushed an 18-foot storm surge ashore in 1954. Hurricane Fran, in 1996, delivered a 12-foot surge. Nevertheless, Pfaff notes, Oak Island and Topsail Island were hit with severe dune and beach sand losses, as well as the destruction of homes, businesses and popular fishing piers.

More misery was in store as Floyd’s rain continued to deluge the coast. Weary residents and emergency workers turned their attention to rising water levels along roadways and riverbanks.

“The rainfall from Floyd was extreme,” Pfaff says.

NWS reported stunning numbers: 19.05 in. at the Wilmington Airport: 16.5 in. at Longwood; 8.85 in. at Shallotte: 7.9 in. at Jacksonville: 14 in. at Elizabethtown; 16.7 in. at Whiteville; 9.8 in. at Lumberton: and 21 in. at Moores Creek. “Hurricane Dennis set the stage for major flooding. Rivers already were running high because of that storm.” Pfaff notes.

By the time Floyd arrived, the ground and the rivers could not handle the added 34 hours of Floyd’s relentless, driving rain.

LETHAL LEGACY

By Friday, Sept. 17, Floyd was gone, leaving coastal counties to cope with its lethal legacy — inland flooding.

An editorial in the Sept. 18 edition of the Wilmington Star-News summed up the growing crisis this way: “The wind was just a diversion. Water was the hurricane’s real weapon.”

Early reports confirmed the paper’s assessment. In Brunswick County, Town Creek and the Lockwood Folly River overflowed their banks, closing sections of U.S. 17 and N.C. 211 — major evacuation routes.

The State Port Pilot reported that North Carolina National Guard medical helicopter crews were airlifting patients to hospitals. Crews transported two pregnant women — one of whom gave birth before landing at New Hanover Regional Medical Center.

Brunswick County emergency workers used airboats on loan from the Charleston Police Department to assist Columbus County in evacuating Crusoe Island residents stranded by rising waters of the Waccamaw River. The Waccamaw crested at 18 feet above flood stage, consuming homes and farmland in rural Brunswick, Columbus and Pender counties.

Meanwhile, most of the region was without electric power — and chances for restoration were dim. Carolina Power and Light reported that substations in Wallace. Whiteville and Grifton were under water. Electric cooperatives’ efforts to restore power also were being thwarted by flooding and impassible roads.

TOUGH LESSONS

In Pender County, there were early signs that Floyd would deliver a one-two punch, says Sheriff Carson Smith, who served as the county’s emergency management coordinator from 1994 to 2002.

“We were getting reports of flash flooding from outer bands of rain before Hurricane Floyd ever made landfall,” he recalls. “By noon, the next day, flash flood warnings were posted, and by evening — 18 hours after the main event – rivers were rising. Many of our citizens were confused and overwhelmed with the sudden rise in rivers, which crested at 23 feet above flood stage in some rural areas.”

The Northeast Cape Fear River and the Black River flow through Pender County. Streams and tributaries, which feed the rivers, also spilled over their banks into many communities. Highway 53 — the main corridor connecting the county seat at Burgaw with much of the county — was under water.

“We were cut off from some areas by flood waters. The only way rescue workers could reach Maple Hill or Rocky Point was by boat or helicopter,” Smith says.

All told, some 1,000 homes in Pender County were flooded to some degree. Two deaths occurred when individuals attempted to drive through flooded roadways — one on 140 near the Duplin County line; and one at Rockfish Creek, west of Burgaw.

FLOYD’S LESSONS

Hurricane Floyd was full of surprises. It was supposed to hit Florida, but took an unexpected turn toward North Carolina. By then, Smith’s attention was focased on evacuating of Topsail Island, which includes the Pender municipalities of Surf City and Topsail Beach, as well as the Onslow County municipality of North Topsail Beach.

With a bridge at each end of the island, evacuation can be accomplished in about eight hours, even at the height of tourist season. Evacuees can travel north on Highway 17, or west on 140.

“Our people are hurricane savvy. Many went to designated shelters. Some went inland. The problem with Floyd was that they couldn’t get back home after the storm passed since a section of 140 was flooded and many local roads were impassible,” Smith notes.

Even so, the slogan “Run from water and hide from wind” is good advice, he contends.

“Yes, Hurricane Floyd was full of surprises. Hurricane Fran in 1999 was supposed to be ‘the big one’ — a 100-year flood. We thought nothing could be worse. Then along comes Floyd — a 500-year flood,” Smith observes.

Floyd demonstrated the importance of communication, coordination and collaboration among emergency managers at federal, state, county and local levels. Interagency conference calls were essential to managing the ongoing crisis — and being able to put resources at the right place at the right time.

Smith says the most important lesson learned from Floyd is that a hurricane is not just a coastal event.

This article was published in the Autumn 2009 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: