COMMUNICATING HURRICANES: Accurate Information, Timely Delivery

If a coastal storm is brewing, where will coastal residents turn for accurate information? How do social, news and other information networks become emergency communications networks?

The answers today are likely quite different than they would have been 10, five or even two years ago.

“The biggest thing that has come across our bow in recent years is how we manage information,” explains Sandy Sanderson, who has led Dare County Emergency Management for 18 years. “People have access to so many information networks. Some are not as accurate as others.”

East Carolina University researchers Catherine Smith, Donna Kain and Ken Wilson have worked with Sanderson and other coastal officials to design and conduct Sea Grant-funded research.

“What communications strategies are working?” asks Smith, whose team will draw conclusions from interviews with hundreds of folks up and down the coastal region. “Which sources do they trust?” she adds. “Many people do not realize that county emergency management information is given through media sources.”

Overall, the ECU team is looking at the ways that people “attend to, interpret, and use official and unofficial information” to make decisions regarding severe weather.

“With coastal community resilience to natural hazards now a major strategic planning focus area for Sea Grant nationally, our earlier funding of this research project was most timely and on target,” states Michael Voiland, North Carolina Sea Grant executive director.

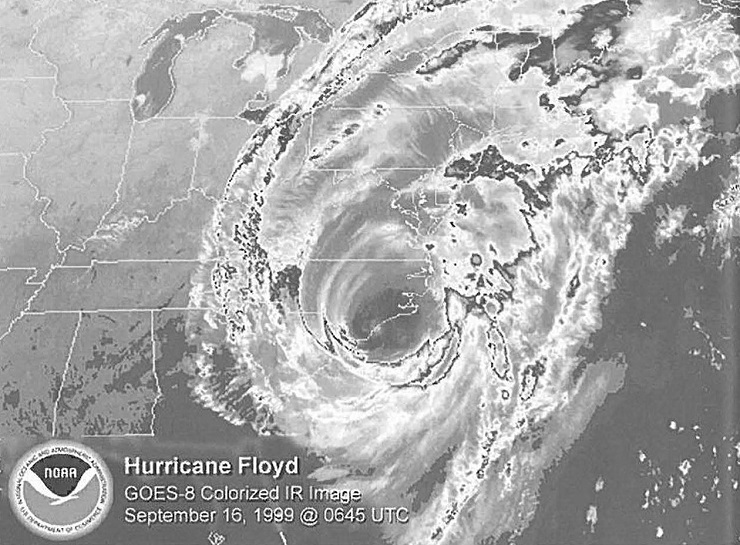

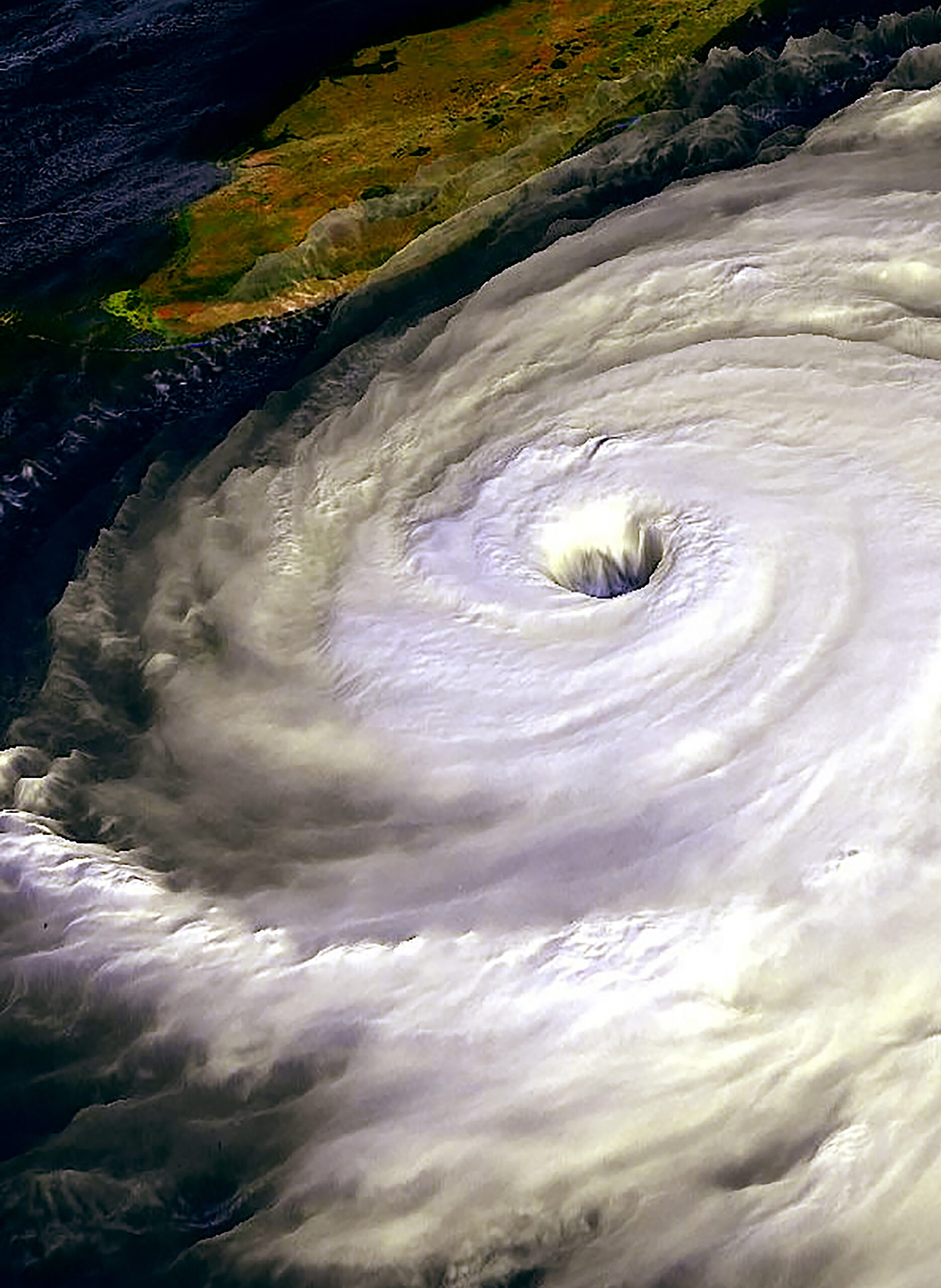

The research team will present preliminary results as part of a Hurricane Floyd Symposium hosted by ECU’s Center for Natural Hazards Research.

For example: 88 percent of year-round residents surveyed have cell phones; 56 percent of those with cell phones use text messaging; but only 18 percent of the cell phone users are now receiving weather alerts via cell phone.

“That is a huge opportunity,” Kain suggests, citing the growth potential for weather alerts to be received on cell phones that people already own.

Sanderson agrees with the researchers that data and recommendations will be critical as counties, towns, businesses and others update storm communications plans.

“They do not have research assistants to stand in parking lots to ask these questions, as we do,” Smith adds with a smile.

STATE OF AWARENESS

Participants in parking lot interviews — in Carteret, Currituck, New Hanover, Dare. Bertie and Pitt counties — often delayed their Food Lion shopping trip or coffee fix by up to 45 minutes to chat with the research team.

In addition to questions about past storm experiences, about 126 shoppers were asked to explain their understanding and likely response to text and graphics from typical tropical storm watch or warning messages.

They were encouraged to describe aloud their thought process in coming to a conclusion, so that the research team can go back through the recorded responses listening for key words or information that is most helpful, or for a particular aspect that is confusing to the public.

“We were surprised that so many didn’t know the difference between a watch and a warning,” Kain says, noting that about a quarter of the preliminary respondents were incorrect in the identification.

Wilson suggests the actual level of misunderstanding may be higher. “You figure that a portion of those with the correct answer had really guessed,” he notes.

Interviewers also presented sample storm-related graphics and asked “What does this mean to you?” Many respondents misinterpreted lines or shaded areas. “Some anticipated that they would evacuate, but they did not evacuate for that storm,” Kain says, explaining that the graphics were from real storms, but the names were left out.

The public’s understanding of storm-warning text and graphics is of interest to the National Hurricane Center. Director Bill Read met the ECU researchers when the NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft came to North Carolina in the spring.

Wilson has headed up a group conducting phone surveys with 1,026 residents in North Carolina’s 20 Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA counties. Many folks identified in the random sample agreed immediately to participate. In other cases, student assistants had to try multiple times to catch a person at home.

Over the summer, another 86 people in the six target counties participated in focus groups or individual interviews. Representing businesses, organizations, schools, hospitals and other larger employers, they shared formal and informal hurricane emergency communications protocols, as well as policies for adjusting operations in response to a pending or present storm.

For instance, participants noted if decisions are made locally, or by officials at a regional or corporate headquarters. Some employers explained that they request personal “storm plans” for staff members who will be needed to work during emergency situations.

Those responses will help the research team develop a final telephone survey this fall to identify attitudes and behaviors of 600 people representing businesses and organizations across the CAMA region.

“What we are learning is fascinating to us and useful to others,” Smith says, adding thanks to Food Lion, public libraries and numerous other community members who have provided locations for the extensive interviewing efforts.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

In response to advances in the Internet and wireless communications, counties are already adapting existing emergency communications plans. Some report that new cell phone transmittal towers are being built on higher ground, with stronger materials, and with generators on site, thus providing critical communications after a storm.

When Hurricane Isabel hit eastern North Carolina in 2003, Bertie County in the coastal plain used its First Call system to dial residents’ phones to give them information about the high winds expected.

“Our shelters were full in advance. We got the word out,” notes Rickey Freeman, the county’s emergency management director. The preparations paid off as the county felt 100-mph winds for three hours, resulting in extensive debris and power outages.

Now, the county is encouraging residents to add cell phone numbers to the system that automatically includes landlines in a geographic area. ”We ran ads, but people don’t like giving out their cell phone numbers,” Freeman says.

The county also has a transmitter that provides a strong signal for the National Weather Service updates sent via NOAA weather radios. In fact, the county got a grant to provide special radios for individuals who are hard of hearing. The radios have flashing lights, as well as a separate piece that goes under a pillow and will vibrate to awaken someone when an alert is issued during the night.

Despite the plethora of personal telecommunications gadgetry that is available, Sanderson agrees that residents of and visitors to our coast should not forget the basic weather radio, because counties base many decisions on the National Weather Service’s watch and warning forecasts.

For example, if forecasts suggest Dare County will be in the path of a storm, the county will begin reviewing potential precautionary steps. If Hatteras Island will need an earlier evacuation schedule than the mainland or northern beaches, those details must be shared with the public.

This year, a Dare County task force is identifying new emergency communications options.

“You can create a Twitter portal in minutes — but you have to tell people that it is available. You have to put it in your news releases,” Sanderson explains, adding that the newest electronic “social networking” may be better at reaching some age groups.

“It is just another tool in our tool bag if we can identify how to use it — and use it correctly.”

This research project will be presented at the ECU Hurricane Floyd Symposium on Sept. 17 and 18.

NOTE: The Hurricane Floyd Symposium Summary Report is available for download.

This article was published in the Autumn 2009 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: