What’s In a Name? Conch vs. Whelk

By TERRI KIRBY HATHAWAY

Seashells of North Carolina photos by SCOTT TAYLOR

Posted March 2, 2015

To quote Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet,

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet.

These two lines imply that the nature of anything is more important than what it is called. But, for a taxonomist who classifies, names and orders things — my first “science-y” job as a marine biologist fresh out of college — that statement just doesn’t ring true!

Through several blog posts, I’m going to share my pet naming peeves with you — common mistakes made by many people. Maybe some will read my posts and correct themselves, but I’m not holding my breath.

First up: conch vs. whelk.

|

|

|

I can’t count the number of times that I’ve heard someone misidentify a whelk by calling it a conch (pronounced konk). To be fair, the word “conch” comes from the Latin word “conchylia,” which translates into the English word mollusk. And many people use the term “conch” to refer to any large marine snail. Conchology is the study of shells, while malacology is the study of mollusks, the animals that make and live in those shells.

Now, for a little scientific background: The phylum Mollusca encompasses all soft-bodied animals with a shell that serves as protection and support. Mollusks are separated into five classes, representatives of which can be found in North Carolina waters, both marine and estuarine. The classes of mollusks are:

- Gastropoda: one coiled shell or reduced/no shell, such as snails and slugs;

- Pelecypoda or bivalvia: two hinged shells, such as clams and oysters;

- Scaphopoda: tusk shell;

- Monoplacophora: chiton; and

- Cephalopoda: reduced/no shell, such as squid, octopus and cuttlefish.

The classes are further divided into families. The Gastropoda class includes the family Buccinidae, where whelks belong, and the family Strombidae, comprised of true conchs. In North Carolina, we have knobbed, lightning and channeled whelks along the entire coast, while milk conchs and Florida fighting conchs may be found south of Cape Hatteras. And even though the shells have a similar look, there are definite differences between the animals.

|

|

|

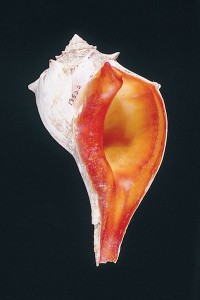

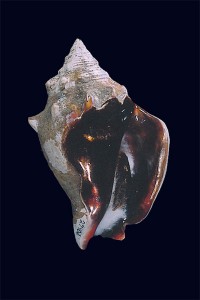

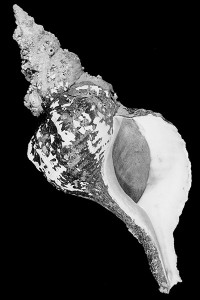

Whelks are carnivores and scavengers in temperate waters, feeding on bivalves and on dead animals and detritus. They crawl around like a snail, using their muscular foot, leading with the narrow end of their shell. Their shells have a wide whorled posterior end, and a long, slender anterior end along which the animal’s siphon is extended.

|

|

|

Conchs usually are found in more tropical areas. They are herbivores, feeding on algae and sometimes on detritus. They do not crawl around, but use a lurching movement by dragging themselves by their operculum or trapdoor. Near the opening of a true conch shell is a “stromboid notch” through which the animal can extend one of its two stalked eyes.

To further confuse this issue, the horse conch — the largest gastropod in North America waters that can grow as long as 24 inches — is neither a conch nor a whelk! It belongs to the tulip snail family (Fasciolariidae). As a carnivore, it feeds on other tulip snails, as well as whelks and conchs.

Conch chowder and conch fritters in Florida and the Caribbean are made from true conchs (Strombidae). Our eastern North Carolina conch chowder is more than likely made from whelks (Buccinidae). Mollusk chowder by any other name is just as delicious! And if you’re wondering about that Italian dish called scungilli (recipe here, and also Lidia Bastianich’s scungilli in marinara sauce with linguine), it’s made with either whelk or conch — but I’m not sure which one.

With a bow to the Bard (and Gertrude Stein and Rudyard Kipling), remember that it was Terri Kirby Hathaway who said: “A whelk is a whelk and a conch is a conch and never the twain shall meet”!

Next up, a discussion of other confusing common names. Don’t miss it!

To learn more about conch and whelk, get a copy of Seashells of North Carolina by Hugh Porter and Lynn Houser.

Other References

- Abbott, R. Tucker. 1968. Seashells of North America. Racine, Wis.: Western Publishing Company, Inc.

- Witherington, Blair and Dawn Witherington. 2011. Seashells of Georgia and the Carolinas: A beachcomber’s guide. Sarasota, Fla.: Pineapple Press, Inc.

- Categories: