A Slow-Motion Emergency

Florence originated where many hurricanes begin, off the west coast of Africa.

In late August, an area of low pressure developed in easterly winds blowing off the continent. Near the Cape Verde Islands, the disturbance became a tropical depression — a cyclone with relatively weak winds. By Sept. 1 it had transformed into a tropical storm.

The system waxed and waned as it churned across the Atlantic, morphing into a major hurricane, then back into a tropical storm, and again into a hurricane.

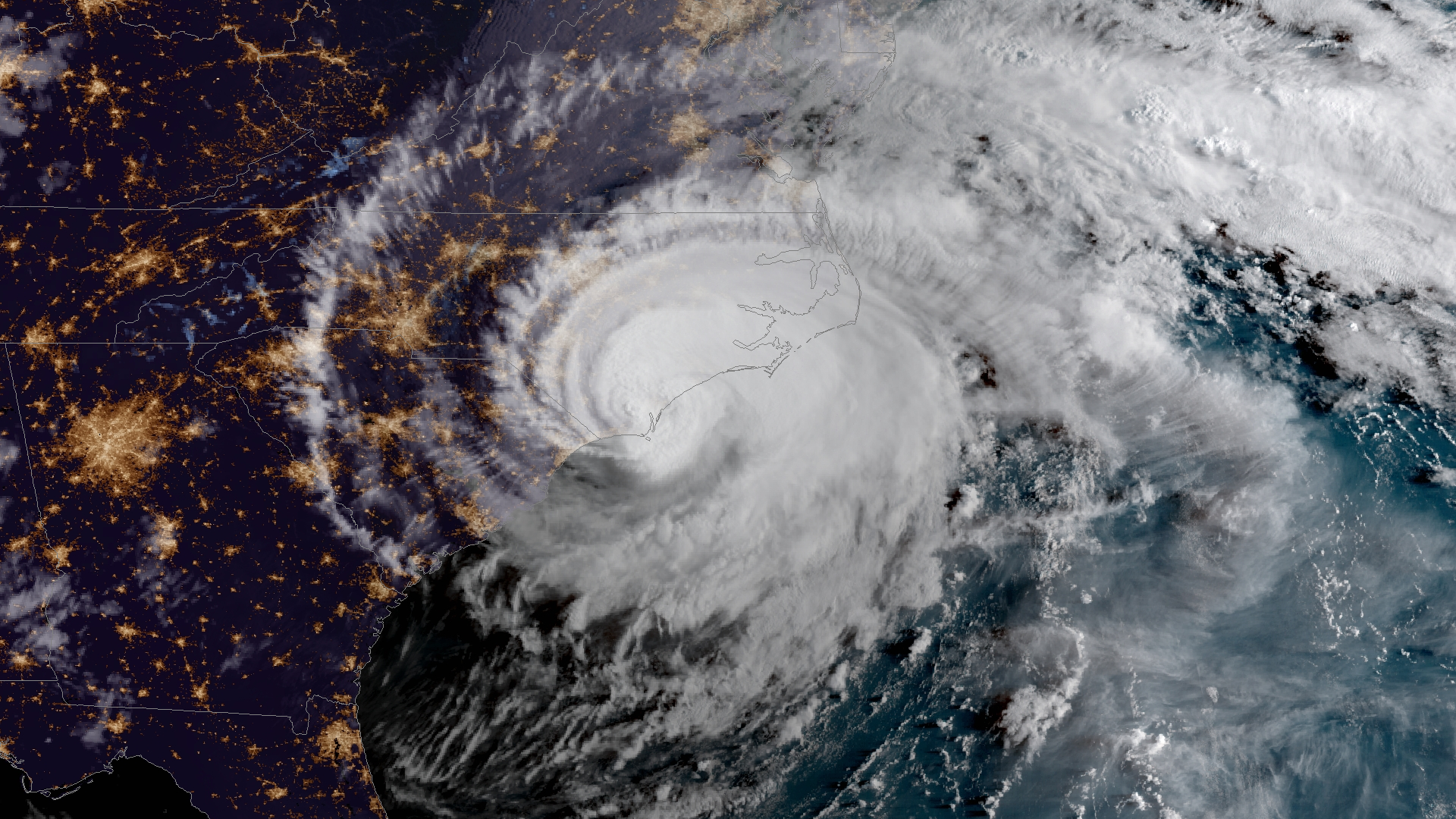

Florence finally made landfall near Wrightsville Beach on Friday, Sept. 14, at a quarter past 7 a.m. With winds whirling at an estimated 90 mph, it was a Category 1 hurricane.

That number, however, describes only one aspect of the storm — its sustained wind speed. Hurricane category doesn’t reflect other attributes such as size, storm surge or moisture content.

“There’s not much of a correlation between hurricane strength and the amount of rainfall production,” says Chip Konrad, director of the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration’s Southeast Regional Climate Center, located at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “A relatively weak system, for example, can produce incredible amounts of rainfall if it stalls out.”

As North Carolinians know all too well, what caused so much devastation in so many communities wasn’t so much the wind speed. It was water – in the form of surge, rain and flooding.

According to Corey Davis, an applied climatologist at the State Climate Office of North Carolina, “it’s safe to say that Florence was the wettest single storm in North Carolina in modem recorded history, since at least 1851.”

Relentless Rains

Florence markedly slowed down as it neared the N.C. coast. The day before landfall, the storm clocked 12 mph. The next morning, it chugged at 6 mph. By Saturday morning, the system crawled over land at a languid 2 mph.

“I think what was really unique was just the sheer amount of time that it was moving slowly along the Carolina coast,” says Konrad, who is also a principal investigator with the Carolinas Integrated Sciences and Assessments, or CISA.

Two high-pressure systems had corralled the storm into an atmospheric cul-de-sac of sorts, blocking it from turning northeastward — as hurricanes typically do — and causing it to stall.

“Florence had no escape route,” says Jessica Whitehead, coastal communities hazards adaptation specialist for North Carolina Sea Grant. The storm instead was forced to take a sluggish southwesterly detour into South Carolina. Along the way, it dumped copious rain.

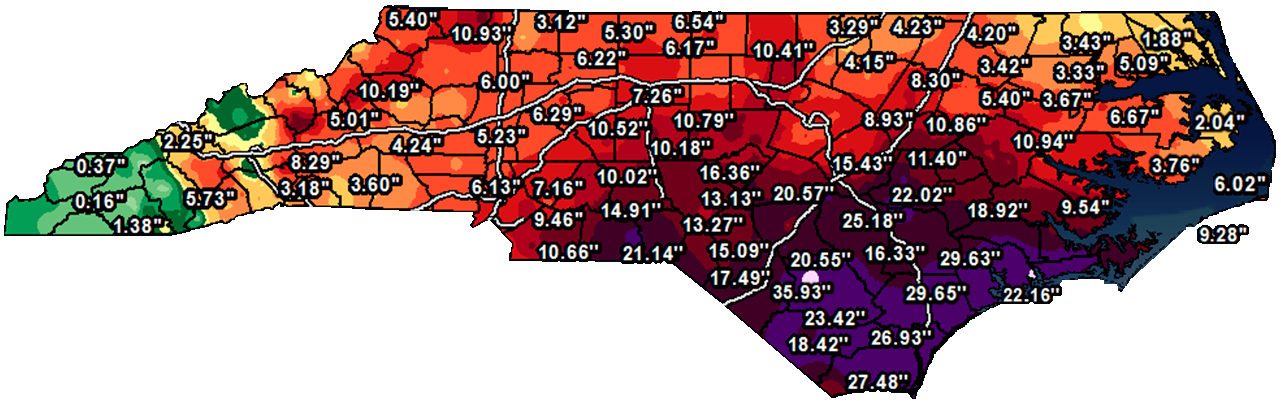

As of 6 p.m. on Sept. 15, for instance, Swansboro in Onslow County near the Carteret County line had received more than an estimated 30 inches. Inland, Hoffman in Richmond County, near the state’s southern border, had seen more than 2 feet by that time.

“The rainfall amounts were just unbelievable,” Konrad says. Preliminary estimates indicate that Elizabethtown in Bladen County received the most, at nearly 36 inches, according to the National Weather Service (NWS). That total breaks the state record for rainfall from a tropical system, set in 1999 by Hurricane Floyd, which drenched Southport in Brunswick County with a smidgen over 2 feet.

According to CISA’s third-quarter newsletter, Elizabethtown “stands out as having received over twice the rainfall expected in a 1,000-year event.” Such an event would be expected to have much less than a 0.1 percent chance of occurring any given year, Konrad says.

Many other locations in the Carolinas, including Wilmington on the coast and Mount Olive inland, also saw 1,000-year rain events, according to CISA.

“I think the prediction of rainfall and the amount that we observed were pretty dam close — and scary,” says David Glenn, the meteorologist in charge for the NWS Newport/Morehead City office. “The reality is, that’s a lot of rain.”

After ensuring their families were safe, Glenn and his colleagues hunkered down in the NWS office for three full days to fulfill their forecasting and warning duties. Their Wilmington counterparts also remained in place for several days, says Glenn, who slept on a broken cot in his office.

Catastrophic Flooding

Though Florence’s winds weakened as it neared shore, the storm grew in size. Its earlier strength and slowing pace set in motion extraordinary surges — notably in riverside areas.

The biggest surge in the state struck New Bern in Craven County, 50 to 60 miles from the hurricane’s center, and inundated the town.

Florence essentially funneled up the Neuse River, causing what NWS forecasters describe as a “catastrophic storm surge” that measured 10.4 feet, according to a rapid-deployment gauge from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Jacksonville, located on the New River in Onslow County, meanwhile saw a surge of more than 7 feet, according to a gauge owned by the N.C. Department of Public Safety. Another state gauge in Belhaven, on the Pungo River in Beaufort County, measured a surge surpassing 5.75 feet.

But storm surge was just a prelude to the deluge to come. Florence’s relentless rains contributed to massive flooding — a hazard that remained for days, and even weeks, after the system made landfall.

Flash flooding transitioned into what the NWS describes as “historic” flooding in Trenton and Pollocksville, located on the Trent River in Jones County, as water crept up to second stories and even roofs. In Carteret County, the Newport River flooded for the first time in recent history, washing through homes and businesses, according to the NWS.

Rivers also saw historic crests, a term used to describe the highest point of a flood wave.

On Sept. 19 in Pender County, the Cape Fear River crested in Burgaw at more than 25.5 feet — almost 10 feet above the “major flood stage” benchmark. That peak surpasses records set by Floyd, as well as by Hurricane Matthew just two years ago in 2016.

In South Carolina, the Waccamaw River near Conway in Horry County crested on Sept. 26 at a hair above 21 feet, shattering the previous record by more than 3 feet.

“If you think about the timeline from when we first saw this storm was a potential threat to the Southeast to the time the floodwaters crest in the lower Pee Dee River Basin, it’s almost two weeks;’ says Greg Carbone, a principal investigator with CISA.

“So, it’s this emergency in slow motion,” he says. “It’s like knowing an asteroid’s going to strike the Earth. It’s not going to be now, but when it happens, it’s not going to be good.”

Distinctive Storms

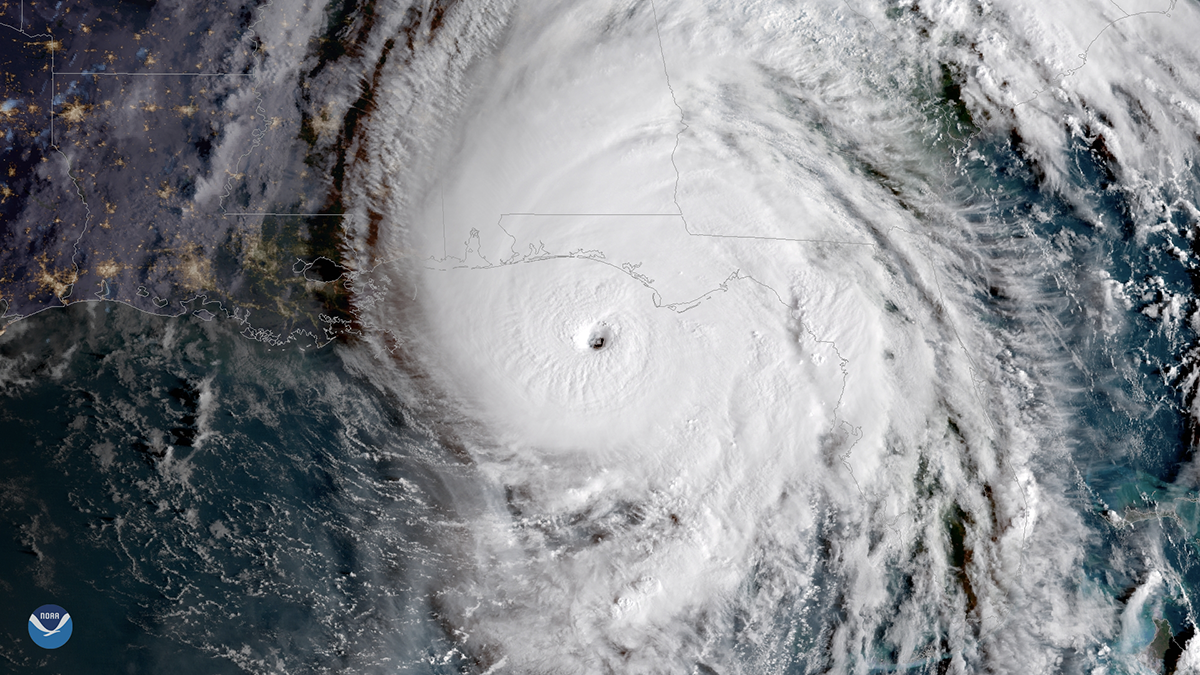

On Oct. 10, less than a month after Florence made landfall, Hurricane Michael roared across the Florida panhandle. A Category 4 storm packing 155-mph winds, Michael was the third most intense hurricane to make landfall in the continental United States, according to NWS records.

Whereas Florence had slowed as it approached land, Michael sped up. As a result, “the flooded area is relatively small, because it was a narrow, fast-moving storm,” says Spencer Rogers, North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal construction and erosion specialist, who was recently on assignment in Florida. “But the wind damage was high enough that it was over a pretty wide area.”

Michael became a tropical storm as it continued to whip across the Southeast. In North Carolina, the system left thousands without power. Wind gusts as high as 74 mph blew through Kitty Hawk, and the Outer Banks saw a sound-side surge of 2 to 4 feet, depending on location, north of Avon.

“There also was tremendous flooding with Michael in southwest Virginia and northwest North Carolina,” Whitehead adds.

The comparisons between Michael and Florence underscore an important fact about hurricanes: No two are alike. As Whitehead puts it, “each storm is its own storm.”

For more details on Florence, check out these summaries from the NWS offices in Newport/Morehead City and Wilmington, as well as this blog post by the N.C. Climate Office.

This article was published in the Autumn 2018 issue of Coastwatch. For reprint requests, click here.

- Categories: