Behind the Researcher: Matt Damiano, Warming Waters, and Sustaining Iconic Fish

“We have a rapidly changing landscape of both the ocean environment and the makeup of who is going out to catch fish.”

When you give a child a National Geographic video on sharks, you might just hook them on sea life.

“I wanted to be a marine biologist, basically from the moment I watched a National Geographic video featuring Dr. Eugenie Clark,” says Matt Damiano, an alumnus of North Carolina State University’s Department of Applied Ecology. “She was my hero growing up.”

Damiano started scuba diving when he was just 13 years old, earning certification when he was 15. But what he saw while diving inspired him to look beyond sharks and instead to the species they eat.

“Sharks are big charismatic creatures, so they’re a good ambassador to the 35,000-plus known species of fish that exist,” he says.

While earning his Ph.D. at NC State, Damiano worked to address fishery sustainability and resource management in the face of warming oceans and changing needs of fisheries.

THE PATH TO BOGUE SOUND

While at Oregon State, Damiano developed an interest in studying fish population dynamics, and then he earned his master’s at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science studying Eastern oysters. After working in fisheries management for two years, Damiano found his way to NC State’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

“I decided that management wasn’t really for me,” says Damiano. “My heart was in research, and that’s what led me to NC State. In 2019, I connected with Jie Cao at the Center for Marine Sciences and Technology.”

“My focus is population dynamics research, which is a specific part of quantitative ecology,” Damiano explains. “It’s about understanding the vital rates associated with fish and shellfish populations for use in management.”

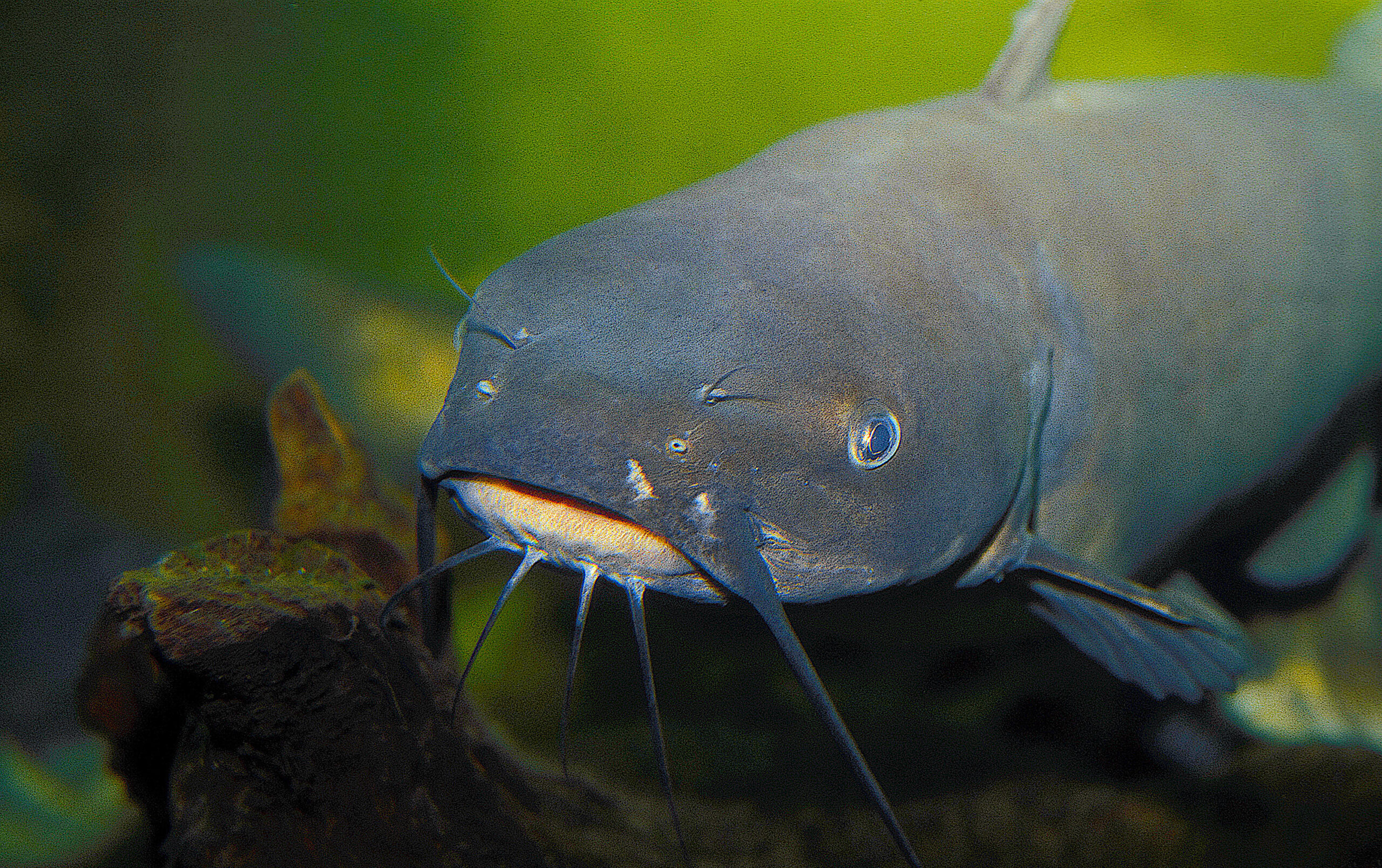

His research at NC State focused on three different fish species, including black sea bass, Atlantic cobia, and mahi mahi, also known as dolphinfish. He received funding for his work through a Marine Fisheries Initiative Grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Marine Fisheries Service-Sea Grant Fellowship in Population and Ecosystem Dynamics.

FROM DOLPHINFISH TO RED SNAPPER

The fish he studied not only play important roles in the ocean ecosystem as predators and prey, but they’re also important in the hospitality and food industries.

“Down in Florida, dolphinfish are considered one of the most iconic fish that you can go catch,” Damiano says. “There’s a lot of economic components that are relying on being able to fish dolphinfish.”

However, the species faces many challenges, including changing ocean temperatures.

“They like to hang out in the Gulf Stream because it has a relatively constant temperature between 70 and 80 degrees. That’s the sweet spot for them. If it gets too hot, they’ll move. If it gets too cold, they’ll move.

What we’re seeing right now is that water is getting a lot hotter off of places like Florida, and it’s getting a lot warmer toward the north.”

Damiano says fishermen in Florida are seeing fewer dolphinfish, and fishermen in the Outer Banks are seeing more.

Dolphinfish are available to fish at different times of the year throughout their range, which extends from northeastern United States waters southward to the Caribbean Sea. To help fisheries managers improve their ability to set sustainable catches, Damiano applied a spatial model to commercial data to estimate population numbers at different seasonal and regional scales.

“We were able to model dolphinfish in a way that seems to make sense biologically and ecologically, and it matches up with local perceptions of how the fish is doing,” Damiano says. “We’re still working some bugs out of the model to try and get the best estimates we can, but I think it’s going to be really important in future work for dolphinfish.”

Damiano currently serves as a postdoctoral researcher in a collaboration with NOAA’s Beaufort Lab and the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, focusing primarily on red snapper, a species that is subject to overfishing. His work involves integrating “close-kin mark-recapture” methods with the red snapper population assessment, using genetic information — instead of traditional physical tagging methods — to make important estimates about the species.

“We have a rapidly changing landscape of both the ocean environment and the makeup of who is going out to catch fish,” he says. “I’m trying to keep up with those changes so we’re able to maintain fishing activity, which is an important component of not just our economy but our identity as a species. It’s an integral component of the way we feed ourselves.”

lead photo credit: Steve Hinczynski.

Emma Macek is a content specialist at NC State University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.