Pelagic birders and fishermen have uncovered secrets in the swirling waters of the Gulf Stream off North Carolina’s coast. They have exposed a global community — an astonishing accumulation of species cruising about or floating in the waves with no land in sight. The endangered black-capped petrel from the Dominican Republic, the arctic tern from icy Antarctica, the sooty tern from Easter Island, all descending offshore and invisible to those folks left on land.

It’s a crisp day as the charter fishing boat approaches the Gulf Stream’s warmer waters. The wind calms to a hush, the sunlight glints diamonds off the water, and the waves flatten a little as the boat gently bobs up and down toward its destination. The ship’s passengers are wired, eager for the day’s events. They mill about, talking shop and dreaming about the possibilities the Gulf Stream holds for them.

Suddenly, the captain shouts; the passengers excitedly ready their gear. In the distance, a Bermuda petrel ascends and drops toward the water. Success! Cameras and binoculars cover excited faces. There are high fives all around. This is a fishing boat, but it is no ordinary fishing trip, and these are no ordinary passengers. This is pelagic birding, and its passengers are offshore for the chance at a glimpse of rare and unusual seabirds.

TRAIL AND STREAM

Of the many sites on the North Carolina Birding Trail (NCBT), pelagic, or open sea, birding is an opportunity that draws birdwatchers from across the United States to spot extraordinary and scarce birds. The state’s proximity to the Gulf Stream is key for open-water birding success.

The Gulf Stream hugs North Carolina’s coast at a distance of 15 to 45 miles from the shore, making it relatively easy for boats to reach. “The Gulf Stream is closer to North Carolina than it is to [most] other places,” says Country Girl Captain Allan Foreman.

John Gerwin, curator of birds at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences, explains. “The Gulf Stream is a two- to two-and-a-half-hour boat ride. You can have four to five hours of good birding in a day.” Many other East Coast locations require longer boat rides to get to the Gulf Stream.

Ted Simons, biologist at North Carolina State University, describes the secret draw for a multitude of pelagic birds. “The edge of the Gulf Stream is where things are really happening,” he says. “The birds are there because the food is there.”

The movement of the Gulf Stream’s warm waters off the continental shelf mixes up nutrients from the ocean’s depths that support marine life such as squid and fish. In other words, the Gulf Stream provides the perfect recipe for lots of bird food. “These birds are really well adapted to traveling tremendous distances to find food,” Simons says. “Many can come from thousands of miles away.”

However, birds aren’t always in the Gulf Stream in search of food. Diamond Girl Captain Donnie Lee explains, “Right after a big storm, especially one coming up from Bermuda, we’ll see birds land on our boat that have no business being in the ocean. We’ll find tiny finches landing on our bow right in the middle of the ocean.

Gerwin also has seen birds that have been blown off course by storms. “There are birds out there that are usually found in the Indian Ocean,” he says. “They might just be lost.”

With the guidance of the NCBT, omnifarious omithologists can find the best birding spots across the state. “The NCBT is a collaborative effort of six organizations,” says Chris McGrath of the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC). In addition to WRC, other trail founders include North Carolina Sea Grant, N.C. Cooperative Extension, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Audubon North Carolina, and the N.C. State Parks.

NCBT offers a series of maps linking the best birding spots across the state. The maps are specific to the mountains, the piedmont or the coast. The coastal map, which can be found at: www.ncbirdingtrail.org, has 102 birding sites, each accompanied by site information such as habitats, species of birds and general site description.

“Birders from all over the world plan trips to North Carolina to see birds they don’t normally see,” says McGrath. The NCBT provides information so birders can know what to look for when they arrive at these birding hot spots.

ONE GOOD TERN

Two such birders are National Sea Grant Deputy Director James Murray and North Carolina Sea Grant Extension Director Jack Thigpen. They gathered friends for a vacation trip earlier this year from Hatteras, guided by Brian Patteson, in search of a “good bird.” Their group included birders from Louisiana, Maryland and North Dakota.

“A good bird is a ‘lifer,’ which is one that I have never seen in North America before,” says Murray, former North Carolina Sea Grant extension director. “The rarer the bird the better.” Avid birders keep track of every bird species they identify on their “life list,” which can grow to hundreds, and in some very rare cases, thousands of species.

Some “good birds” include the Bermuda petrel and the black-capped petrel, both endangered species that birders have spotted while pelagic birding off the North Carolina coastline. “The shearwaters were also really cool,” says Thigpen, who has a life list topping out at 289 North American bird species. “I saw both a Cory’s and an Audubon shearwater. I added those to my list when I went out.”

Thigpen is particularly impressed with shearwaters’ ability to take advantage of the varying air pressure close to the water’s surface. It is a broad-winged bird with a horseshoe tail that can shear the air with its wings like a knife or lope gracefully along the water’s surface. “They use the waves to surf the air,” he says. “Just watching them maneuver was amazing.”

Gerwin keeps a mental note of his life list of more than 2,000 species, but the chance of catching a glimpse of a lifer is still invigorating enough to get him out into the waves. When talking about the great shearwater, he says, “I still get excited when I see them. I get seasick but I’ll go see these birds because it’s worth it.”

Patteson, who has guided hundreds of pelagic birding trips as captain of the Stormy Petrel II, is less fascinated about the actual birds he sees than he does about their unique behaviors. “I’m still excited to see some of the behaviors of even the more common birds,” he says.

“It won’t be long now before the terns will be flying in. The young ones will follow the adults. You can watch the adults catch fish and feed it to the young right there over the water. I think that’s pretty neat.”

CREATURES APLENTY

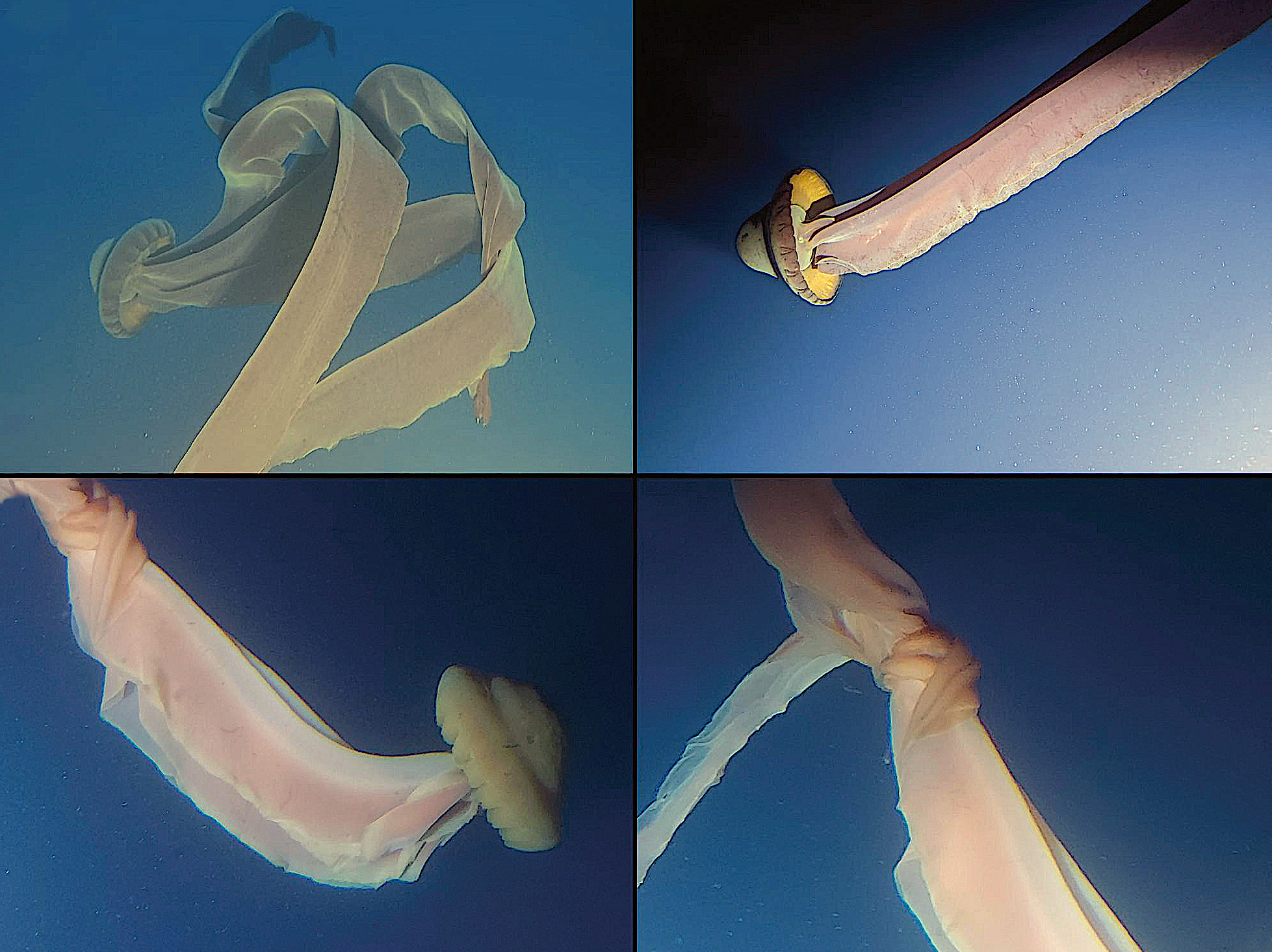

Often, birds are not the only animals spotted on pelagic trips. Foreman and Patteson report seeing everything from sea turtles to sperm whales on birding trips. “We’ve seen some pretty interesting stuff that a lot of people never get to see or have never heard of,” says Patteson. “Just last weekend, we saw beaked whales. We don’t see these animals every time, but we see them regularly.”

Thigpen reports a bounty of beasts bobbing in the waves on his pelagic birding trip. “I knew going on this trip that I’d be seeing some bird species I’d never seen before, but I’d never thought that much about what else I’d see.”

He spied four species of dolphin, three species of whales, and loggerhead turtles on the trip. “These creatures were up near the top of the water, and the whales and dolphins were swimming close, curious about the boat.” At one point. Thigpen watched a humpback whale jump completely out of the water. ‘This mammal, as big as a minivan, crashing back onto the water creates quite a sound and sight,” he says.

Before the advent of pelagic birding. much of the avian life of the open sea was a mystery. “Nobody understood or knew who was using this part of the ocean before except fishermen” says Gerwin. “We still have a lot of birds that people are finding out there. Brian [Patteson] has even documented a couple of birds new to the area that have never been documented out there before.”

Some captains, like Patteson and Foreman, will take birding-only trips and will have a spotter with expert bird knowledge to point out “good birds.” These trips are great for beginner and expert birders alike who prefer guidance on their trips. However, there are plenty of fishing charters like Captain Lee’s Diamond Girl out of Morehead City that are willing to take birders any time.

“Just don’t be surprised if we drop a line while we’re out there.” Lee says. “I think we captains would find it mighty hard to be all the way out there without dropping a line.”

That can be music to the ears of many birders. “I think catchin’ fish while you’re out birding is a bonus,” says avid birder Clyde Sorenson.

BIRD BUCKS

In addition to providing birders with names to add to their life lists, pelagic birding and the NCBT also give a financial boost to local communities. “There are a number of ways that birding as a form of outdoor recreation enhances the local economy,” says McGrath. “Birders stay at local hotels and purchase meals at local restaurants,” and that money goes directly into local communities.

According to a 2006 FWS survey, visitors spent over $160 million in North Carolina and Virginia wildlife refuges. These visitors list birding as their second primary activity, next to fishing.

Local businesses can capitalize on these “bird bucks.” The NCBT website lists “birder-friendly businesses” in site cities. The website also has “birder calling cards” that birders can print out and leave at businesses they stop by on their journey. “This helps businesses market their facilities to birders,” McGrath says.

Vanessa Foreman, wife of Alan Foreman and owner of Big Al’s Soda Fountain and Grill in Manteo, welcomes birding business. “Sometimes the birders will bring fish from their pelagic trips down to my restaurant and we’ll cook their fish for them,” she says.

In addition to providing a financial boost to landlubber businesses, pelagic birding can benefit fishing charters because many birds can be spotted in the fishing off-season. “The Gulf Stream waters are always warmer, so we can book birders in the early spring, winter and fall, when other business is down,” Captain Foreman says.

“Many of these species return to land only to breed. Some are in the ocean from August to May while others are out there in the summer months. You can find different birds out there every month,” Gerwin adds.

Despite this fact, there are some better months for birding than others, Patteson explains. “People want to go either during spring migration or later summer when you have Caribbean nesters that disperse and come up here. In January and February, the coldest part of the winter, we have a few birds that come up then.”

BIRDS OF A FEATHER

Locals concur that the birder populace does not resemble the typical fisherman or sightseer. “Birders are so cute,” Captain Foreman says. “They always have a lot of pens in their pockets.”

He describes the reactions of birders when they spot lifers from the boat as different from fishermen’s reactions to fishing, “In general, they’re a lot more laid back than your typical fisherman,” he says. “But one day we saw three rare species of petrels in about a half hour: a fea’s petrel, a herald petrel and a Bermuda petrel. Oh man, they high-fived and hooted and hollered when they saw those!”

Patteson has also seen the differences between fishermen and birders. For instance, he notices that birders provide a more diverse clientele. “Birders often fly in from all over the country,” he says. “Most fishermen drive in because they are already on vacation.” Patteson attributes the distance traveled to birders’ greater willingness to push the limits of rough weather for the chance at spotting a lifer.

“They know they might never come back again,” he says.

An Ocean of Birds: Build Your Own Life List With These Coastal Birds

- Black-capped petrel: This endangered nocturnal bird has odd-sounding mating calls, which have earned it the name “Diablotin,” meaning “little devil,” in its mating range of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

- Bermuda petrel: Until the 1950s, this sea dweller was thought to have been driven to extinction by Spanish colonists in the early 1600s. Today, the population is considered endangered but on the mend.

- Red-billed tropicbird: These long-tailed pelagic birds breed on tropical islands but sometimes can wander far from home. There have been sightings of red-billed tropicbirds as far away as Great Britain.

- Arctic tern: This highly migratory bird sees two summers every year as it makes its annual 44,000-mile round-trip around the oceans of Antarctica. This is currently the longest-known distance for any regular animal migration.

This article was published in the Holiday 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: