Capturing the Culprit: Carbon Sequestration and the Battle Against Climate Change

By protecting coastal ecosystems, we can take advantage of nature’s own tools for capturing carbon from the atmosphere — and help to slow down global warming.

On January 8, 2016, scientists arrived at Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, North Carolina, for a day of fieldwork.

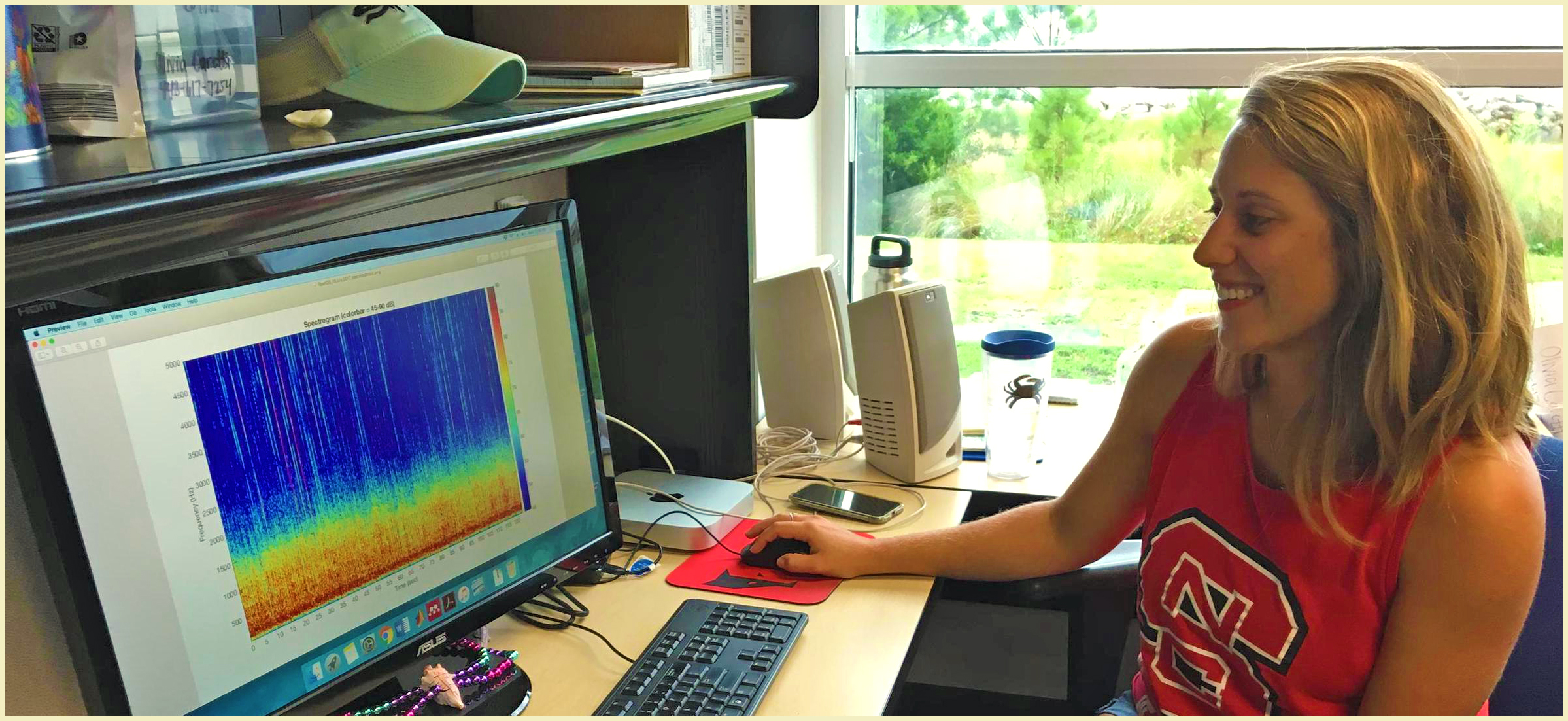

Researchers have conducted several studies at Camp Lejeune since 2009 to understand the complex ecosystems that provide the training setting for the largest Marine Corps base on the East Coast. On this day, Carolyn Currin and Nathan McTigue from the NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science in Beaufort collected a sample of the marsh (a “sediment core”) from 7 feet below ground. Radiocarbon dating later determined the sediment contained carbon that the marsh had stored for almost 2,500 years.

These scientists’ work highlights the critical role of coastal ecosystems in removing carbon from the atmosphere. Last year, Currin and McTigue published a study based on the sediment they collected in 2016, noting that the high rates of carbon buried over time in wetland sediments have “garnered attention as a potential ‘natural fix’ to reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere.”

The buildup of carbon in the atmosphere, of course, accelerates global warming — with sizeable consequences. By 2060, the small town of Beaufort in eastern North Carolina, for instance, will experience a foot of sea level rise under NOAA’s lowest sea level projections and potentially as much as 2 to 4 feet as the global climate continues to warm over the next 40 years. Higher temperatures will result in significant challenges for coastal habitats and communities, including many of the places on the North Carolina coast and around the country that are of important cultural, social, ecological, and economic value.

The Carbon Culprit

Carbon, an element found in all living organisms, is the chemical backbone of life, and it is second in abundance only to oxygen in the human body.

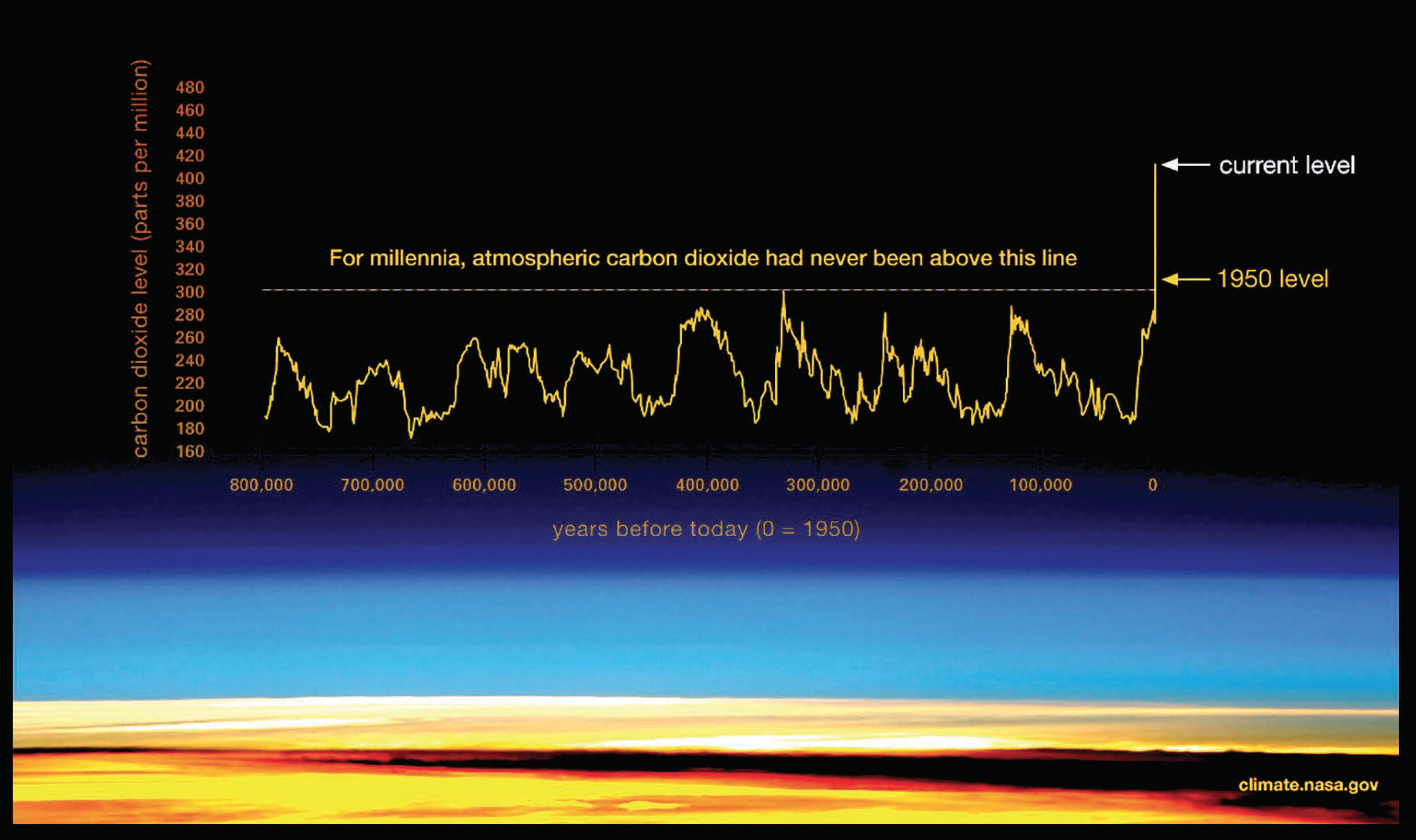

The overall amount of carbon on our planet remains relatively fixed, but the way it is stored changes as it cycles through the environment and through living organisms. Oceans, for example, store about 50 times more carbon than the earth’s atmosphere.

Changes in the amount of carbon in our atmosphere, however, result in significant impacts. As greater amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases enter the atmosphere, oceans warm and acidify, icebergs melt at a faster rate, and sea levels rise.

Our coastal communities experience climate change most severely in the forms of more intense storms, greater rainfall, and rising seas. Hans Paerl at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Science in Morehead City published a study last year noting that six of the seven highest precipitation events on record in North Carolina have occurred within the last 20 years. Increasing rainfall and hurricanes such as Floyd (1999), Matthew (2016), and Florence (2018) have brought catastrophic flooding, adverse economic impacts, and ecological damage that has included the increased runoff of pollutants into coastal ecosystems and estuaries.

According to NOAA’s Blue Carbon: “Current studies suggest that mangroves and coastal wetlands annually sequester carbon at a rate 10 times greater than mature tropical forests. They also store three to five times more carbon per equivalent area than tropical forests.”

Capturing the Culprit: Carbon Sequestration

Studies of Camp Lejeune sediment cores have shown how coastal ecosystems play an important role both in “sequestering” (capturing) and storing carbon.

According to Currin, salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass beds absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it underground for extremely long periods of time. “By using radiocarbon dating,” she says, “we were able to determine that marsh plant material buried at the bottom of a 2-meter deep core was 2,460 years old.”

Currin and her colleagues estimated that carbon has accumulated in the sediment for the past 100 years at a rate almost four times higher than it has for the past 1,000 years. The rate of carbon burial over the lifetime of this marsh typically correlates closely with local sea level rise; thus, the recent increase in stored carbon could be due to accelerated sea level rise in North Carolina.

Of course, North Carolina is replete with vast tracts of salt marshes. Over hundreds of thousands of years, sediment has layered on these marsh ecosystems. As sediment layers continue to build on top of previous layers, carbon remains stored deep within coastal habitats. Through photosynthesis, marsh plants take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and then convert it to plant matter. Because this organic plant material becomes buried under sediments, decomposition occurs over thousands of years — in effect, keeping the carbon stored — as compared to forest habitats where decomposition occurs over mere decades. Most of the living organisms in terrestrial forests exist above ground and, thus, break down after death at a faster rate due to much higher exposure to light and oxygen.

Currin says marsh ecosystems are more effective than any other type of habitat in the world — including terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems — at the sequestration and storage process. However, she warns, the accelerated rate of sea level rise might significantly affect carbon storage in coastal ecosystems.

“Although sea level rise brings more tidal water and sediments into the marshes,” she says, “we’re finding that our low marshes in North Carolina are not keeping up with sea level rise, and carbon accumulation will end quickly if the marshes convert to mudflats.”

Even more importantly, as these habitats disappear, they also will release hundreds or thousands of years’ of stored carbon into the atmosphere.

“Tactics to prevent further warming also often help us adapt to the warming that has already happened.”

–Letter from the Editor, 2019 Audubon Society Special Report on Climate Change

Preserving Marshland

We can try to slow down or adapt to the changes in climate that are already well underway. Preserving and restoring salt marsh habitats and mangrove forests remain an incredibly important piece of the puzzle. However, even if we were to preserve and protect all saltmarshes successfully, these habitats cover insufficient area globally to singlehandedly solve climate change. We won’t be able to salt marsh our way out of this problem.

In addition, as Currin cautioned, rising sea levels could drown marshes, not only ending the capacity of the land to store carbon but also releasing carbon that had already been stored. In fact, a 2019 Special Report on the Ocean and Crysosphere from the United Nations

intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that 20 to 90% of coastal wetlands will disappear by the year 2100.

In North Carolina, however, a new statewide approach could bring important protections to our coast. In 2018, Governor Roy Cooper signed Executive Order 80 (EO80): North Carolina’s Commitment to Address Climate Change and Transition to a Clean Energy Economy. By doing so, he also brought recognition to the importance of the state’s coastal habitats. EO80 instructs the state to accomplish specific climate-related goals, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 40% below 2005 levels by the year 2025, integrating climate change mitigation and adaption practices into all cabinet agency programs and operations, and preparing a “Climate Risk Assessment and Resiliency Plan” this year.

Of course, coastal habitats are at the forefront of the battle of land versus rising waters in North Carolina. As part of the EO80 efforts, the Natural and Working Lands (NWL) Stakeholder Group is making recommendations to build ecosystem resiliency, sequester carbon, and provide economic growth through the conservation, restoration, and management of the state’s inland and coastal terrain. To inform the statewide resiliency plan, the Coastal Habitats Subcommittee of the NWL has developed strategies and viable on-the-ground actions that will protect and restore North Carolina’s vital coastal habitats.

The subcommittee’s recommendations will include measures that value coastal habitats both for their carbon sequestration and storage benefits and for the ecosystems services they provide. These ecosystems provide vital habitats for marine life, shoreline protection, opportunities for outdoor recreation and tourism, and a supply of seafood. Fostering these healthy ecosystems will serve to make the state better prepared to adapt to the challenges of climate change.

A multi-pronged approach with diverse partners and solutions, through Executive Order 80 and other efforts, is instructive for how to continue tackling climate change challenges at state, national, and global levels. Many residents in North Carolina’s coastal communities already are thinking about how to work together. The solutions will be complex, and the best approaches will offer equitable and affordable ideas.

A collaborative group of partners from many different organizations serves on the state’s Natural and Working Lands Stakeholder Group’s Coastal Habitats Subcommittee, which is making recommendations for the N.C. Climate Risk Assessment and Resiliency Plan.

• N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries

• N.C. Division of Coastal Management

• North Carolina Sea Grant

• NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

• The Nature Conservancy North Carolina

• Defenders of Wildlife

• Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership

• Carolina Wetlands Association

• U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

• Audubon North Carolina

• Duke University

Read more:

• Carolyn Currin, Nathan McTigue, and other scientists conducted research at Camp Lejune as part of the Defense Coastal/Estuarine Research Program (DCERP)

• U.N. Special Report on the Ocean and Crysosphere

• N.C. Climate Risk Assessment and Resiliency Plan

Sarah Spiegler serves in a dual role as the program coordinator of the N.C. Sentinel Site Cooperative (NCSSC) and as a marine education

specialist for North Carolina Sea Grant. She works collaboratively with NCSSC partners to address the impacts of sea level rise on North Carolina coastal habitats and communities. She helps to bridge the gap between science and real-world policy solutions, translating sea level rise and climate change science for managers and local government officials. She also serves on the state’s Natural and Working Lands Stakeholder Group’s Coastal Habitats Subcommittee.

- Categories: