Emerging Contaminants: Why Do These Alligators Have Infections?

The Autoimmune Effects of Exposure to PFAS

A recent study of alligators in the Cape Fear River found they had elevated levels of 14 different per-and plyfluoroalkyl (PFAS) chemicals in their blood serum, as well as clinical and genetic indicators of immune system effects.

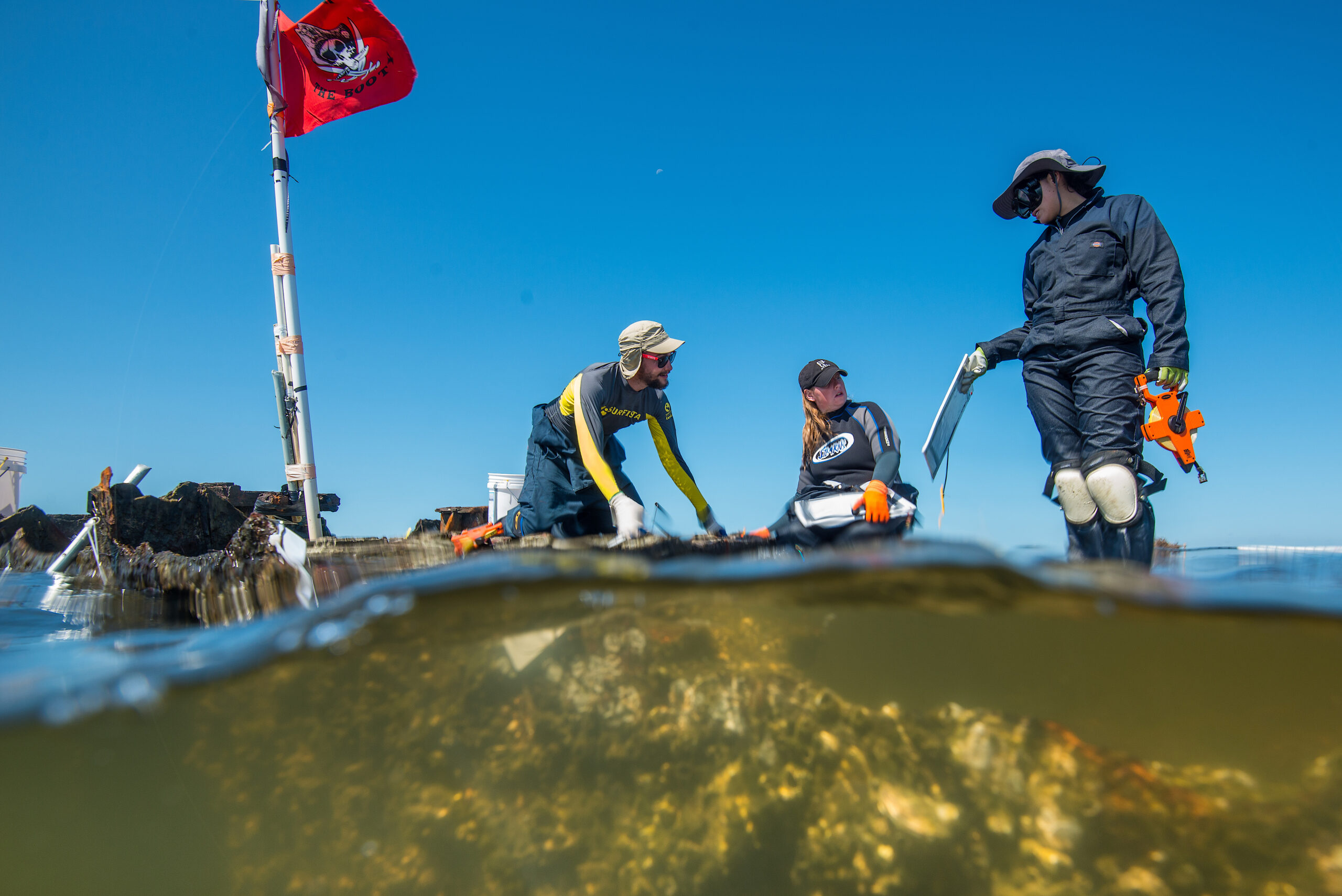

The research team, led by Scott Belcher, associate professor of biology at North Carolina State University, did health evaluations on 49 alligators living along the Cape Fear River. They compared these results to a population of 26 alligators from Lake Waccamaw, located in the adjoining Lumber River basin.

“We looked at 23 different PFAS and saw clear differences between both types and levels of PFAS in the two populations,” says Belcher, who earlier this year participated in a United Nations panel on chemical waste and pollution. “We detected an average of 10 different PFAS in the Cape Fear River samples, compared to an average of five different PFAS in the Lake Waccamaw population. Additionally, blood concentrations of fluoroethers, such as Nafion byproduct 2, were present at higher concentrations in alligators from the Cape Fear River basin, whereas these levels were much lower — or not detected — in alligators from Lake Waccamaw. Our data showed that as we moved downstream from Wilmington to Bald Head Island, overall PFAS concentrations decreased.”

UNHEALED LESIONS — AND WHAT THEY INDICATE

The most unusual observation the team made was that alligators in the Cape Fear River had a number of unhealed or infected lesions.

“Alligators rarely suffer from infections,” Belcher says. “They do get wounds, but they normally heal quickly. Seeing infected lesions that weren’t healing properly was concerning and led us to look more closely at the connections between PFAS exposure and changes in the immune systems of the alligators.”

Genetic analysis revealed significantly elevated levels of interferon-alpha (INF-α) responsive genes in the Cape Fear River alligators: their levels were 400 times higher than those of the Lake Waccamaw alligators, which had much lower PFAS blood concentrations.

“When we see elevated expression of INF-α in these alligators,” Belcher says, “it tells us that something in these alligators’ immune responses is being disrupted.”

HARBINGERS

With five years’ worth of sampling data, much of it taken from the same alligators on an annual basis, the researchers are in a good position to continue following PFAS exposure and health changes in both individuals and the larger alligator populations within both habitats.

“Alligators are a sentinel species —harbingers of dangers to human health,” Belcher says. “Seeing these associations between PFAS exposure and disrupted immune function in the Cape Fear River alligators supports connections between adverse human and animal health effects and PFAS exposure.”

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory supported this work, along with a Community Collaborative Research Grant, funded by North Carolina Sea Grant, the NC Water Resources Research Institute, and the Kenan Institute for Engineering, Technology and Science.

Tracey Peake writes for NC State University News, which published an earlier version of this story.

- Categories: