Resilience and Redevelopment in Duffyfield

After Hurricane Florence flooded an African American neighborhood with a long history of strength after adversity, a team of community leaders, researchers, and students has been working to restore housing and preserve community history.

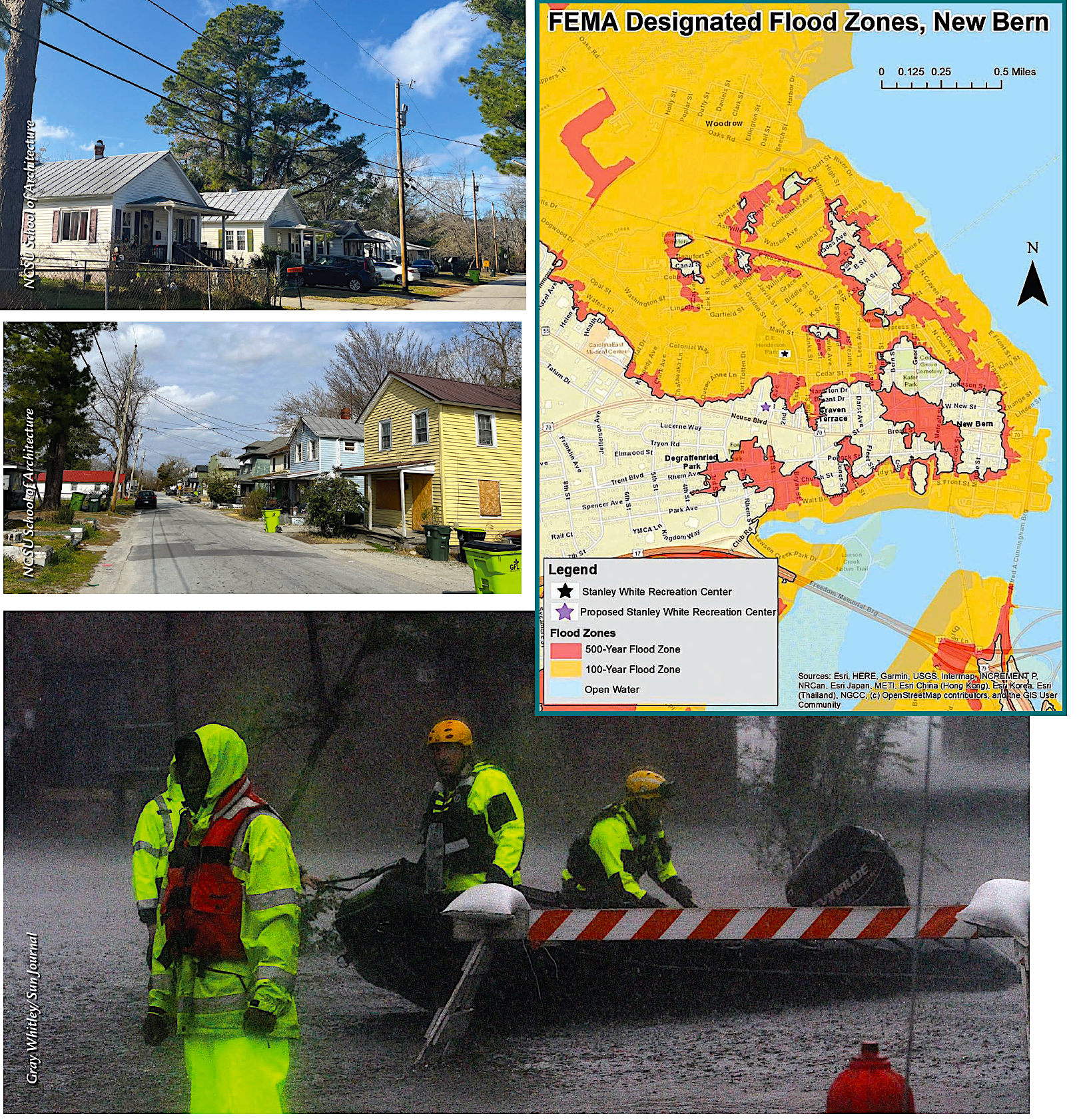

On September 14, 2018, Florence — a large and slow-moving hurricane — made landfall and spent the next two days producing a record-breaking 30 inches of rainfall across eastern North Carolina. In the city of New Bern, Florence was responsible for approximately $100 million in damages, mostly due to flooding.

The cost of natural disasters continues to rise due to increased community exposure and vulnerability, as well as climate change. According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, 2018 was a very active year for the United States, which experienced 14 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters.

Of those, eight were severe storms, including Hurricane Florence. New Bern is home to the Duffyfield neighborhood, a vibrant and resilient African American community that has withstood racial, economic, and land-use discrimination. As a result of the impacts of extreme weather events, neighborhoods like Duffyfield have continued to suffer years of periodic flooding and disinvestment, as well as population and housing losses.

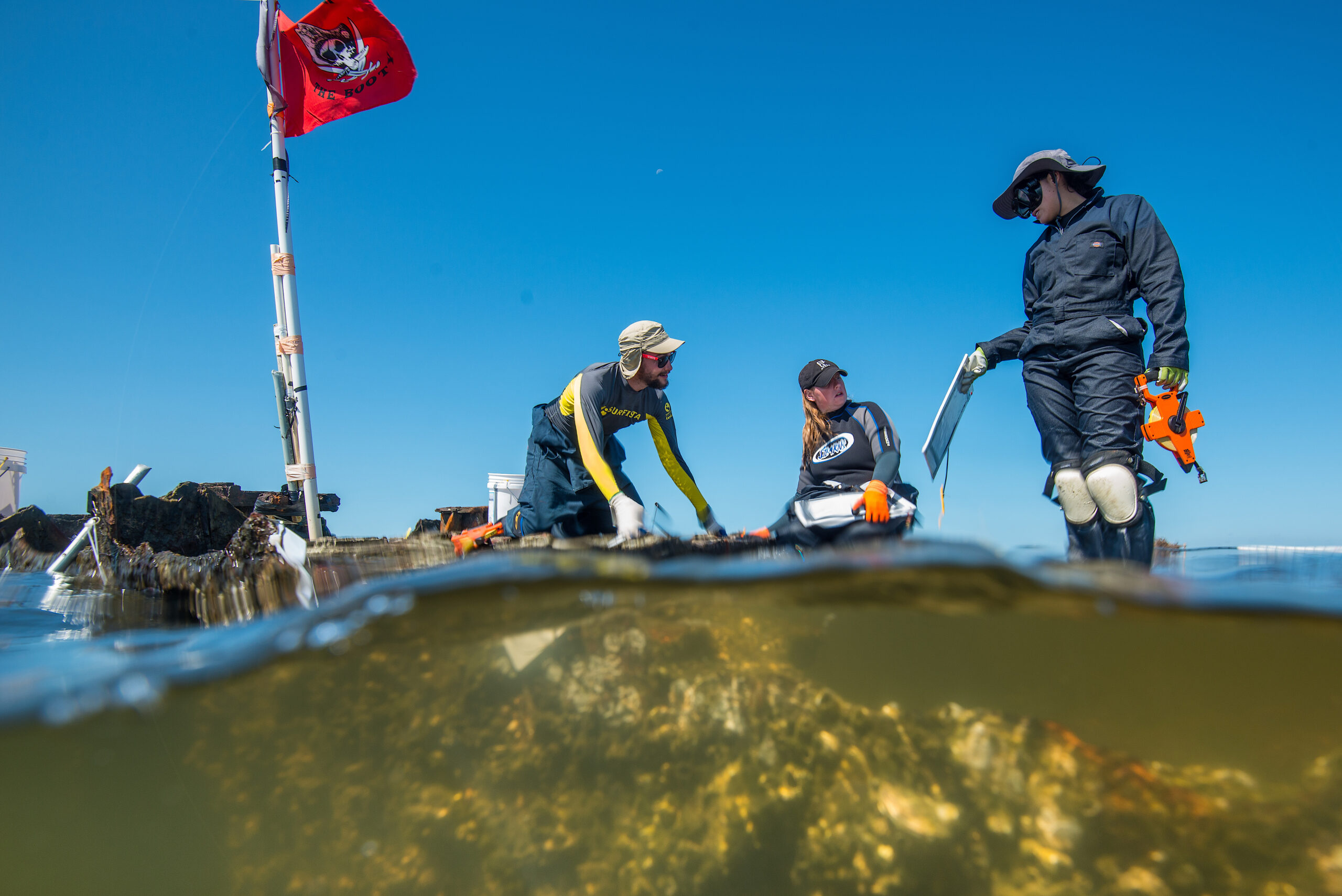

The disproportionate effects of flooding involving under-resourced and underrepresented communities have been the subject of ongoing work at North Carolina Sea Grant and the NC Water Resources Research Institute.

“We have to consider that there are a lot of locational challenges, and some communities that will always be vulnerable to flooding,” says Frank López, extension director for both programs.

“We want to make people safer, but don’t want people to have to lose what they feel is their neighborhood. How do you create something that will still serve the community that is there — without having it change — but try to do something that will reduce the vulnerability of future floods?”

Welcome to Duffyfield

Close to 32,000 residents call the city of New Bern, North Carolina, home. Founded in 1710, it is well-known as the second oldest colonial town in North Carolina — and also the birthplace of Pepsi.

The history of its Black culture is less known. After the Union Army seized New Bern early in the Civil War, the city became a sanctuary for enslaved people, and some would become community leaders after the war. Jim Crow laws later repressed Black communities, and by the 1940s New Bern became a majority- white city.

In the 1960s, protests and sit-ins at a New Bern restaurant helped advance civil rights, but disparities have continued. Today, Duffyfield experiences high crime rates, poorly maintained roads, very few sidewalks, and health and education inequities.

Additionally, the damage from hurricanes, especially Hurricane Florence, has left the community with challenges for rebuilding housing. Although much of the built heritage of Duffyfield has been lost, many community members and leaders want to continue to restore what has been damaged and conserve what is still present.

“We want to conserve and create an image that when you ride by and you see it, you say that image and that brand is me, and it represents me,” says Jamara Wallace, chair of the Greater Duffyfield Residence Council and president of The Greater Duffyfield Residents.

In all, 12 subdivisions make up Greater Duffyfield. Its lower lying areas are subject to flooding, which threatens property, health, and life, but the Duffyfield neighborhood is sacred to its residents.

Wallace wants to keep flood mitigation at the top of the city’s list of priorities.

“Our African American roots are here — our grandparents, great grandparents — and these roots and ties to the area goes back generations,” says Wallace. “The city is aware that extreme storms like Florence happen, and it is nature at work. But in the event that smaller storms push through, we need to be able to work efficiently and figure out ways to push the water out.”

A New Model

With support from Sea Grant, Frank López and David Salvesen, director of the UNC Institute for the Environment’s Sustainable Triangle Field Site, reached out to community leaders in New Bern. Two topics were high priorities.

“The city’s idea was for us to come up with suggestions for vacant parcels in Duffyfield that would improve quality of life,” says López, “and also to provide affordable housing options to stabilize the neighborhood.”

Duffyfield has an abundance of rental properties, and over 40% of its properties are vacant.

López and Salvesen partnered with directors and managers of the New Bern Boys & Girls Club and New Bern Habitat for Humanity. The team’s main goal was to figure out how to maintain a community’s cohesion after flooding and heighten its resilience, using Duffyfield as a model.

“We needed a kind of template for people to have,” says López. “New Bern is not the only place along the coast that is vulnerable to disasters and redevelopment issues in the aftermath.”

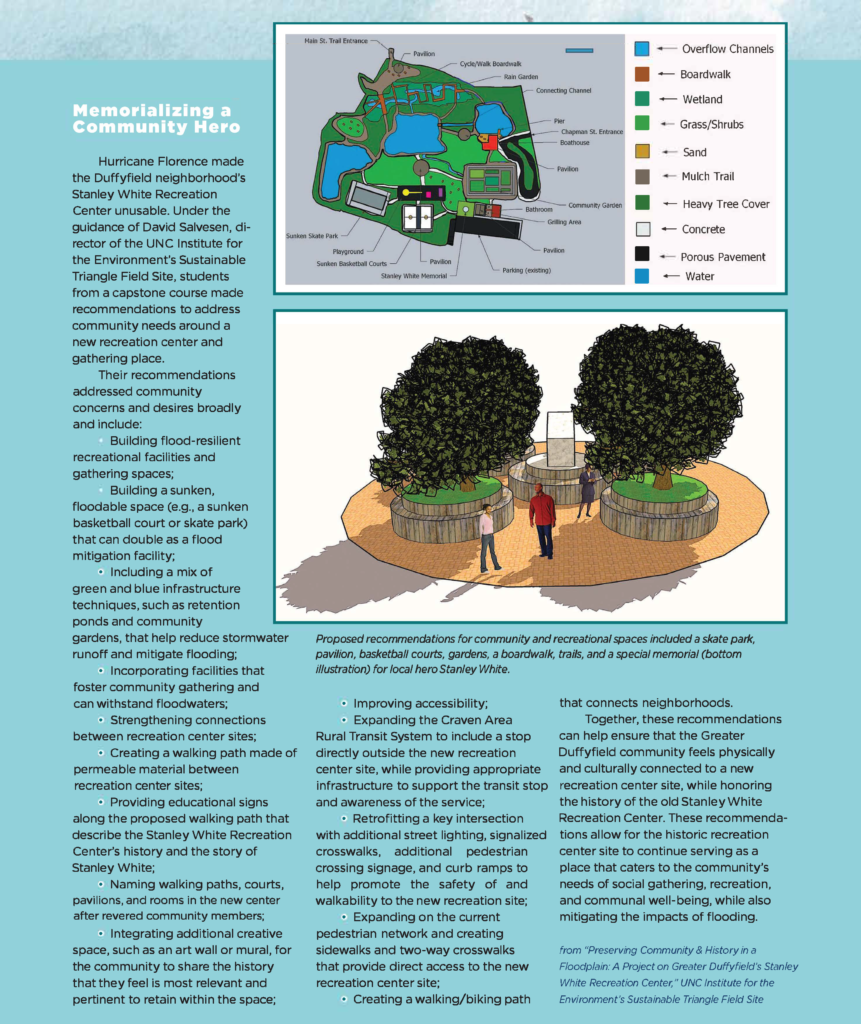

The Stanley White Recreation Center is the centerpiece of the Duffyfield community. For kids and adults, it has served as a place of gathering, recreation, and fellowship. Its namesake was an African American athlete, born in New Bern, who had a tremendous impact on the local Black community and who tragically died in 1971 while participating in a baseball game.

The 46-year-old facility is located in a floodplain. Floods from Hurricane Florence destroyed its foundation, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency does not allow rebuilding in places where there has been repeated flooding. Although there are plans to build a new center outside of the floodplain, concern has grown among the neighborhood, which is eager for a solution — a solution that one resident says is necessary to keep “public trust.”

From the Ground Up

Under the direction of Salvesen, students from a capstone class at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill used several educational modules, which included background on climate change, storytelling, flood mitigation, and flood plains. The students also engaged with Duffyfield community members, conducting surveys and interviews, as well as researching case studies of cities with parks that were proactive in managing floodwater.

“The Boys & Girls Club leadership felt like the youth really hadn’t had a voice in discussions or decisions about the recreation center,” Salvesen says. “And they asked us if we could somehow engage their students in a process where they would learn about issues like hazard mitigation, climate change, sea-level rise, and also have a chance to share with us what they would like to see happen with the new recreation center.”

UNC student intern Elizabeth Mitchell soon found herself drawn to the Duffyfield project. Majoring in political science and environmental studies, she would work with another student intern to gather information. They went on site visits and talked to community members.

“The community members had so much to share,” Mitchell says. “From the outside looking in, it could look really simple. Your house keeps getting flooded. Why don’t you move? But for people who live there, that’s their land, their home. This is where their family lives. I felt that was a really important part of meeting the people and hearing their stories, and making sure we were keeping that in the forefront of our work going forward.”

The project shaped Mitchell’s perspective, and she credits it for informing her as a graduate student now in both city planning and environmental management. Her capstone class developed an extensive report, including recommendations about honoring Stanley White with a new space. (See “Memorializing a Community Hero” below.)

Into the Studio

To begin converting some of the community’s recommendations into solutions, students from NC State University’s School of Architecture studio worked to provide several design options for affordable housing as part of Duffyfield’s redevelopment.

“My primary mission is to educate future leaders,” says Thomas Barrie, director of the Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Initiative at NC State. “It’s my hope that some of them will go out and have careers working in areas like affordable housing, social equity, spatial justice, and environmental justice.”

The School of Architecture’s studio classes are meant to broaden the lenses of students, while also offering many design and research opportunities. The Duffyfield project illustrated the social mission of architecture, according to Barrie.

“Ultimately, we serve the public, and this was unique in that it taught students how to apply design skills and knowledge to address persistent problems,” he says.

The students designed affordable and resilient housing for a flood prone area — a real need in North Carolina. They created housing plans that included duplexes and triplexes, some with smaller on-site “accessory” dwelling units, while still making residences look like single family houses with garages in the back — a feature that some community members hadn’t considered but grew to like. Some students designed townhouses, showing five or six attached together, or two units attached in a “U” shape, creating efficiency and affordability.

Throughout this process, the students’ work was reviewed by Matthew Schelly, New Bern’s interim director of development services at the time.

“I was quite impressed with the variety of various solutions and the variety of factors or issues that each one of them stressed in their designs,” Schelly says. “Some of them were concerned about community engagement, or just architectural design to enhance community, while some were much more focused on the construction parameters to make them as inexpensive and affordable as possible.”

Duffyfield Now and Tomorrow

“New Bern is one of few communities that has facilitated a city planning process to develop its own resilience plan,” says López.

Resiliency work with the Duffyfield community continues. Even after the students’ semester long projects have ended, old and new collaborators continue to work toward the community’s redevelopment.

As for the Stanley White Recreation Center, Jamara Wallace says he hopes that stakeholders continue to keep the city’s focus on flood mitigation plans and the center’s completion. Currently, it is on schedule for rebuilding in one to two years — at a new site on higher ground.

“For both kids and adults, the new facility will serve a lot of different purposes,” Wallace says. “It will be a shelter in emergency situations, a place of refuge. Wanting to keep in mind the current needs of recreation in the 21st century, it will also have multiple basketball courts and other rooms.”

Since Wallace served as chair of the Greater Duffyfield Residents Council, there have been additional plans to help build capacity for holding and capturing stormwater, as well as for a new wetlands project. Several initiatives are also in the process of incorporating additional pumping stations to help move the water out.

“We are proud of our neighborhood, and we want to continue to improve and make changes, and make sure that the quality of life is good,” he says.

Salvesen and López both hope to continue their work in New Bern.

“It just points out the power of visualizing what might happen,” says López. “And giving people the opportunity to think about their neighborhood, and the future.”

Lauren D. Pharr is an award-winning science communicator with North Carolina Sea Grant, contributing editor for Coastwatch, Ph.D. student at NC State University, and 2021-2022 Global Change Fellow with the Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center.

more