Sands of Time

A sandbar shark tagged in North Carolina waters resurfaces 23 years later off the Florida Keys.

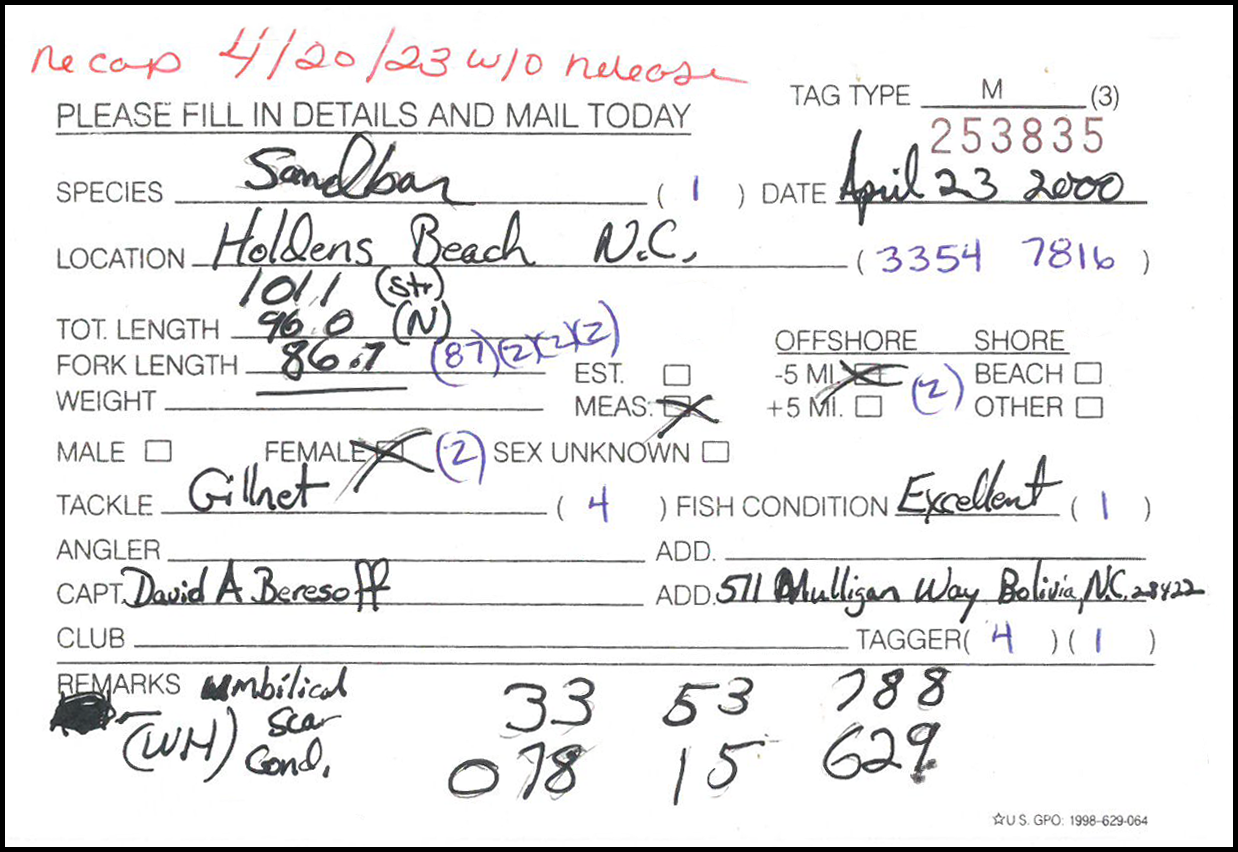

On the deck of his boat, seasoned commercial fisherman Dave Beresoff meticulously fills out the small matching card for M Tag number 253835. Just moments ago, he implanted the tag below the dorsal fin of a small shark and tossed it back into the water.

SPECIES: Sandbar

LOCATION: Holden Beach, NC

FORK LENGTH: 86.7 cm

FEMALE: (X)

TACKLE: Gillnet

FISH CONDITION: Excellent

In the REMARKS section, Beresoff notes that the young shark’s umbilical scar was well healed, along with providing the current GPS coordinates. Under the date, he writes April 23, 2000 and he doesn’t think about the small shark again for more than two decades.

Last June, Kate Zewinski, the coordinator for NOAA’s Cooperative Shark Tagging Program, was fervently attempting to locate Beresoff to inform him that the sandbar shark he had tagged 23 years prior had been recently caught off the Florida Keys. The recapture marked one of the longest times a shark has been at liberty in the roughly 30 years she has been involved with the program.

Affixed to all deployed shark tags are compact waterproof capsules containing research-related messages in English, Spanish, French, Norwegian, and Japanese, along with a promise of a reward for reporting a recapture. When Zewinski receives news of a recapture, she enters the tag number and other information about the shark into the program’s database and generates a comprehensive report with the shark’s growth, movements, the original tagger’s name, and their contact details. Both the tagger and the individual who recaptured the shark receive a copy of this report, along with the reward.

There was just one problem: Beresoff’s outdated address was the only contact information on file.

Since tagging the young sandbar shark all those years ago, Beresoff has moved from North Carolina to Florida and back again, making Zewinski’s task of finding and notifying him of the extraordinary news more challenging. “I actually really didn’t think I would find Dave,” she admits.

Without a phone number, email, or current address, Zewinski resorted to Facebook. After searching using his name, she combed through the results until she found a profile picture of a man on a fishing boat. Taking it as a potential lead, she messaged him about tagging sharks. Her hunch paid off: it was Dave Beresoff.

Intrigued, Beresoff responded a few days later with details about his past research with North Carolina Sea Grant, recalling how he used to tag sharks as a hobby whenever the opportunity arose. In late April 2000, he participated in a research project that incidentally caught sharks in gillnets. Making the most out of the situation, they chose to tag the sharks that were in optimal condition, increasing the likelihood of their survival.

Beresoff surmised this individual sandbar shark must have been tagged within the scope of a project assessing North Carolina’s population of spiny dogfish. He was surprised and thrilled to learn of the recapture. “It’s like putting a note in a bottle and casting it out to sea, hoping that you will get a response!”

Zewinski was happy to share the news of the recapture after 23 years. “There aren’t many with that length of liberty,” she says. “So, when we get those, it’s exciting.”

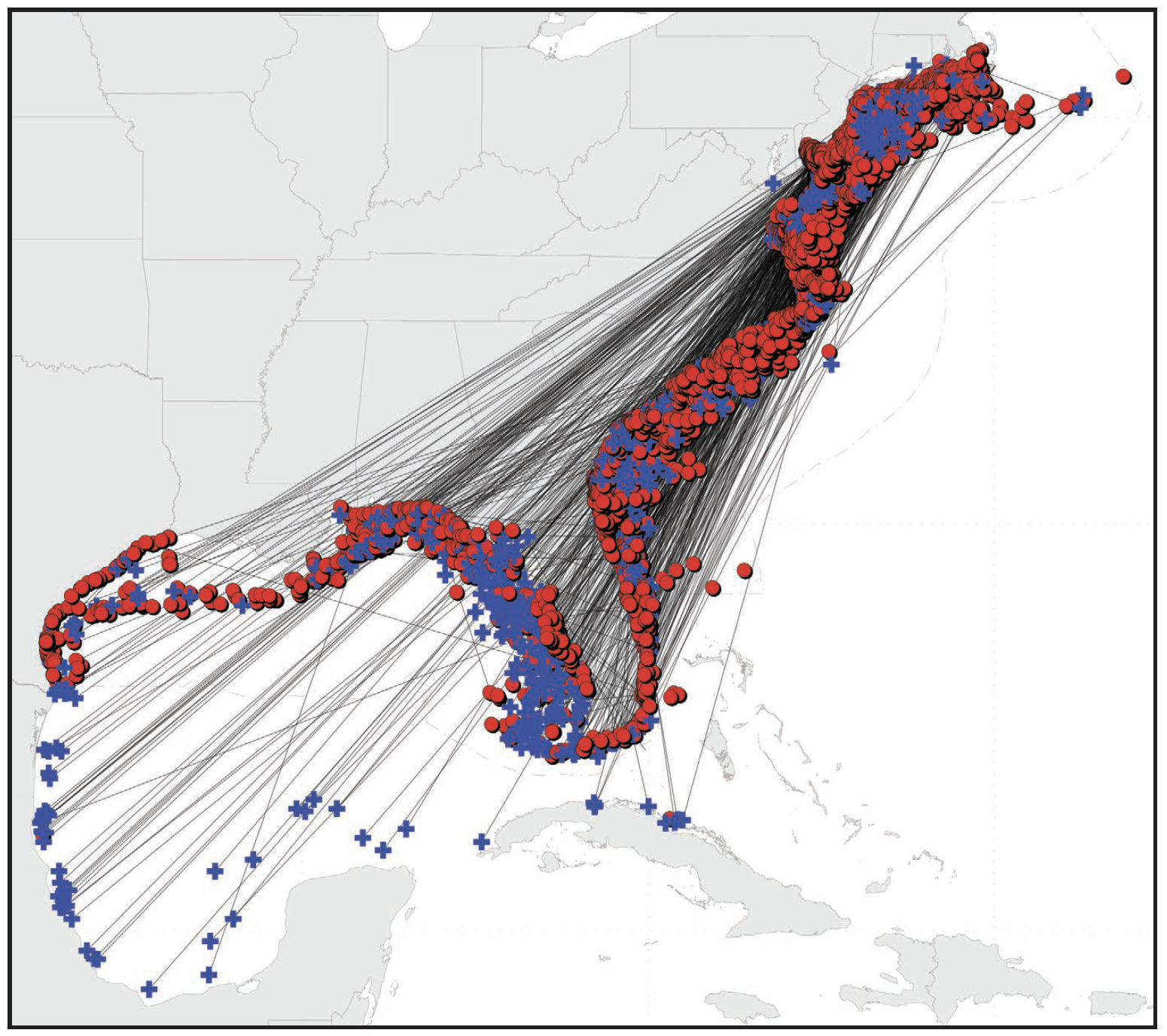

Beresoff’s sandbar shark had an astonishing and rare 8,397 days before being recaptured — a remarkable feat for the Cooperative Shark Tagging Program, the world’s largest and longest-running shark tagging project, which began in the early 1960s. The program is a collaborative effort among recreational anglers, the commercial fishing industry, biologists, and NOAA Fisheries, aimed at studying the life history of sharks in the Atlantic Ocean.

Since its creation, Cooperative Shark Tagging Program participants, have tagged more than 300,000 sharks, which includes over 50 shark species, along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Among these, more than 18,000 have been recaptured, contributing to recapture data on more than 30 shark species. By 2023, sandbar sharks accounted for just under 50,000 —around 15% — of the tags deployed, with a recapture rate of 4%. The current record for time at liberty is held by another sandbar shark at 28 years.

Recapture events aid researchers in gaining crucial insights about sharks, providing details like stock structure, distribution, movements, migration patterns, population abundance, age, growth rates, behavior, and mortality. The tagging program contributes essential data for various assessments, both on a local and global scale.

During its time at liberty, Beresoff’s female sandbar shark grew to a length of 5 feet 4 inches before recapture 890 nautical miles southwest of Holden Beach, North Carolina, where he originally had tagged it. Ultimately, a commercial fishing vessel south of Marathon in the Florida Keys caught it.

Zewinski says that the location of the recapture was typical for the species, which follows seasonal patterns along the East Coast. Sandbar sharks tend to favor cooler waters during summer months, migrate south in winter, and generally remain close to shore. On average, they can live to be 35 to 41 years old in the wild.

The product of a lifetime on the water, Beresoff understands gear usage, fishing locations, and the various species along the North Carolina coast, both from commercial and recreational standpoints. His skillset made him an asset to many research grants in the late 90s and early 2000s. “When you combine that with the academics, it’s the greatest collaboration you could ever possibly put together,” he says.

Beresoff’s sandbar shark was tagged during a study that looked at the distribution and reproductive status of spiny dogfish in North Carolina waters and their susceptibility to incidental take by commercial gillnets. At that time, there was some domestic demand for spiny dogfish, but stocks were overfished due to bycatch mortality and the targeting of large mature females.

“The Fishery Resource Grant Program allocated roughly a million dollars annually towards innovative research in North Carolina fisheries at the time,” says Scott Baker, fisheries specialist at North Carolina Sea Grant. He emphasizes that the program enabled fishers to test and validate their ideas under scientific scrutiny, with North Carolina Sea Grant playing a pivotal role in building connections between scientists and fishers. Although the program was discontinued, Baker notes how it exemplified the cooperative rapport between fishers and researchers, which steered many management decisions. Its success would also influence new collaborative funding opportunities offered by North Carolina Sea Grant.

The sandbar shark was the first recapture of what Beresoff suspects were hundreds of sharks he has tagged, whether through similar projects or commercial fishing ventures. Throughout his long career, he has recaptured a few tagged sharks himself, though, in both North Carolina and Florida waters.

He also has engaged in several other tagging initiatives over the years, including Atlantic sturgeon and red drum. He credits his college background in marine science, in part, for his interest in collaborating with researchers, as well as his service on North Carolina’s Marine Fisheries Commission and numerous federal panels.

And this shark’s recapture after 23 years caused Beresoff to reflect. “In 2009, a freak wave sank my boat, and my crew and I had to swim to the beach,” Beresoff shares. The disaster upended his long-standing commercial fishing operation in North Carolina. “After that, my whole world kind of fell apart — mine and my wife’s – we struggled.”

He and his wife decided a fresh start would be best. They moved south to Ramrod Key in the Florida Keys, a place they had annually vacationed for many years. Embracing their new surroundings, they found perspective and continued to pursue their passion for fishing by making a successful living off the ocean again.

The irony of the shark he tagged in North Carolina showing up again offshore of the Florida Keys is not lost on him. “I tagged this shark 23 years ago and here it is – it made the same journey I did in life!” he jests.

The Beresoffs eventually returned to North Carolina for a common and heartwarming reason: they had become grandparents. Today, Beresoff and his wife work in a fish house, and he is starting to fish commercially again.

If you would like to get involved with NOAA’s Cooperative Shark Tagging Program and help build the knowledge base about sharks in the Atlantic, you can reach out to Kate Zewinski at sharkrecap@noaa.gov. To report a recapture, call toll-free at 877-826-2612, email sharkrecap@noaa.gov.

Dan DiNicola is the science and digital media editor for Coastwatch. His feature “An Angler-Inspired Approach: How Descending Devices Can Save North Carolina’s Reef Fish” recently earned a science journalism award from the Science Communicators of North Carolina.