Mention red drum to Jim Bahen and you are certain to transport him to that mystical place of all recreational anglers: the record book.

Bahen, Sea Grant recreational fishing extension specialist, would love to be the one who breaks the record set in 1984 when a 59-inch, 94.2-pounder was snagged off Hatteras.

In those days, the angler could haul the fish to shore and proudly pose for the traditional trophy picture. Bahen knows the “big ones” are out there. After all, the red drum — the state’s designated saltwater fish — is believed to live up to 60 years or more.

But to protect dwindling stocks, today’s regulations limit recreational anglers to keeping one 18- to 27-inch red drum on any single day. Bahen hopes someone will be there to document the moment he lands his dream fish before he returns it to the water, and it becomes a legendary “one that got away.”

Not that Bahen is complaining. He is a staunch advocate of catch-and-release techniques for recreational fishers. He also sits on an N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission (MFC) advisory panel that is developing a red drum fishery management plan. The idea, after all, is to protect the species during its spawning years and, in time, boost the numbers. More about that later.

First, let’s consider facts about the red drum — also known as channel bass, puppy drum, or redfish.

Named the state saltwater fish in 1971, red drum, not surprisingly, get their name from their color. What’s more, during spawning, males produce a drum-like noise by vibrating a muscle in their swim bladder. Its scientific name, Scianops ocellatus, means perch-like marine fish (Greek) with eye-like colored spot or spots (Latin). Red drum bear black spots, on each side near the base of their tails. These fool predators into attacking the tails, not the eyes — buying escape time for the fish.

According to the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF), red drum live in coastal and estuarine waters from Massachusetts to Mexico. Bottom feeders, they prefer crabs, shrimp, menhaden, mullet and spot. Reaching sexual maturity during their fourth year, when they are about 30 to 37 inches long, they spawn in the near-shore ocean waters around tidal inlets in late summer to early fall. Their eggs hatch and are carried into the sounds and estuaries by the tides and winds.

The red drum depend on estuaries during the early stages of their life cycle, seeking quiet shallow water with grassy or muddy bottoms. They remain in the sounds and estuaries or in the surf zones along inlets for the first three or four years of their lives.

To understand more about the red drum life history, Sea Grant researcher Peter Rand is studying its spawning habitat. Rand hopes to document the salinity range that best supports egg and larvae survival.

STOCK STATUS AND REMEDIES

The DMF lists the red drum as “stressed-declining” because of stock status reports of a dramatic decline in the number of red drum reaching maturity. The division began tagging red drum in 1983 to determine seasonal occurrence, migration and growth. Between 1991 and 1993, only 1 percent of the 9,000 juvenile tagged were recaptured as spawning-sized adults. “Spawning potential ratio” is used to determine the health of a fish stock. The ratio for a healthy population is 40 percent. But for the North Carolina red drum, the ratio is less than 10 percent.

As part of the Fisheries Reform Act of 1997, fishery commissioners began to appoint advisory councils to help develop management plans for each of the state’s commercially and recreationally important marine fisheries species, including the red drum. These plans will form the basis for future regulations for species, species groups, fishing gear and geographic areas.

Bahen says the work of the red drum advisory committee is nearly complete. In October, the MFC will act on advisory committee recommendations and public comments.

Meanwhile, anglers are sticking to interim measures — size and harvest limits — to help restore stocks of the popular red drum fish. While no recreational salt water license is required in North Carolina, Bahen stresses that individuals are obliged to learn and abide by rules for each fishery. “It’s a matter of ethics,” he says.

YEAR-ROUND FUN IN THE FIGHT

Bahen asserts that anyone who ever has fished for red drum knows the fun is in the fight, no matter how you measure the landing. Open for harvest year-round, red drum puts the skills of fishing veterans to the test. “You’ll know when you have a red drum on the line. The red drum is a fighter and will give you a run for your money,” Bahen attests.

The beauty of the red drum is that you can put your line down in virtually any kind of coastal water in North Carolina — from estuarine rivers and streams to open sound, inlets, surf and creek banks.

“You can sight-cast red drum. They show themselves,” Bahen explains. “At high tide, they’ll go into the marsh and root around. You may see the movement of the grass. The sight of the dorsal fin just above the water’s surface is a clear signal of feeding red drum — an invitation to drop your line.”

Surf fishers should look for the red drum’s golden red glistening through breaking waves or in fast-moving inlet waters. They’ll need to select gear to match larger fish usually found at these sites. Bahen suggests using rods from 7 to 10 feet, or longer, and 10- to 15-pound test line to accommodate the size of the fish and the churning water.

As for bait, red drum don’t seem to be picky eaters. Though they prefer natural bait, such as cut mullet, they will bite on artificial lures or top water bait. Red drum are becoming a popular target for light tackle fly fishing enthusiasts, he notes.

Bahen prefers to use the circle hook and natural bait in his catch-and-release, recreational fishing pursuits. “All the research indicates that the circle hook reduces fish mortality because it catches the fish in the comer of its mouth. It is rare to see a gut-hooked fish.”

To minimize damage to the fish, don’t jerk the line to set the hook, he says. The circle hook is designed to slide into the comer of the fish’s mouth as the fish takes the bait and begins to swim away. Once the fish is reeled in, hold the fish gently at the water surface to remove the hook. “Take time to admire your catch as you examine it for gill damage before releasing him,” Bahen urges.

If it is difficult to remove the hook, Bahen says, release the fish, hook and all. Most circle hooks are made of steel that will break down and fall away from the fish in time.

Circle hooks were introduced in North Carolina as part of a bluefin tuna catch-and-release program several years ago. They are catching on for use with different fish species to increase fish survival and help bolster stocks.

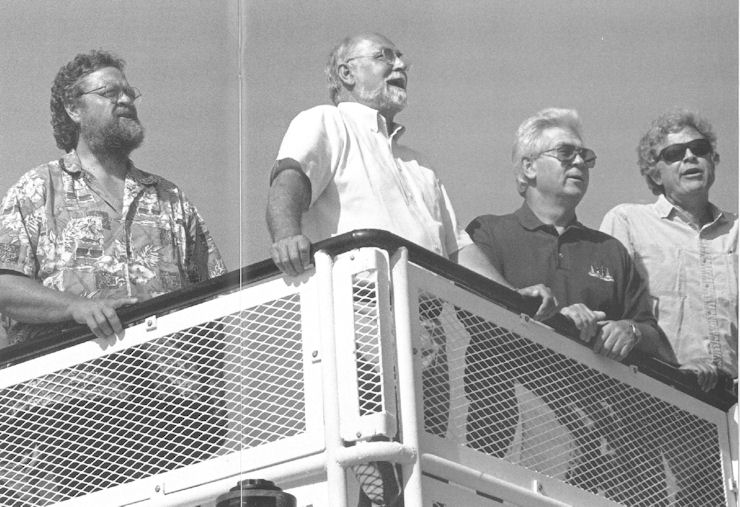

Meanwhile, polling along Howell’s Creek near Wilmington, the pressure is on for Bahen to catch a red drum model for the Coastwatch article. Conditions are not the best. An overnight rain has made it difficult to spot fish through the murky, mud-stirred creek. A small flounder takes the bait quickly. Bahen releases it for another time.

A couple of hours pass and Bahen and local guide, Tyler Stone, are about to give up. Photographer Scott Taylor encourages one more try. A small red drum obliges, and Bahen plays his catch long enough to enjoy the encounter. Then, Bahen reels in the fish to demonstrate proper handling and releasing techniques.

A good size red drum for dinner for three is about 21 inches. Baked, broiled or blackened, it ranks up there with speckled trout or spot, Bahen says.

But the perfect size red drum, according to Bahen’s calculations? That would be a record-breaking 95 pounds.

The red drum is not a commercially targeted fish, but may be taken as by-catch. However, there is a 1OO-pound daily trip limit for commercial fishing vessels.

This article was published in the High Season 2000 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: