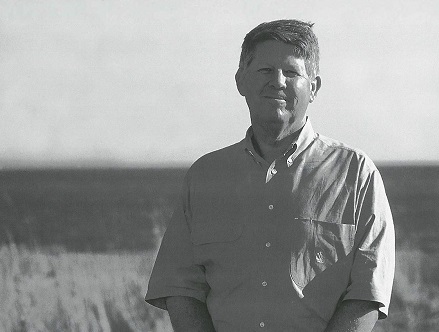

Growing up on the Outer Banks, Marc Basnight learned a bit about weathering storms — like the time his mother, Cora Mae, explained about hurricanes.

“When Donna came, I remember Momma taking me outside and standing in the eye as it passed over and everything was calm,” he says. “Now don’t get me wrong, she never wanted one — but she told us why the Good Lord brought hurricanes.”

The storms, his mother explained, were part of the cycle of nature. “There was a reason.

It had to happen,” he recalls the lesson, one of many from his youth that resonates as he serves as president pro tempore of the North Carolina Senate.

“It still affects me — how I look at things. If you live in a city of concrete, you vicariously experience the environment,” he says. ‘When you grow up in a coastal community, you know the value of the environment — that you need to protect these lands that are part of the food chain.”

That perspective shows when Basnight calls for wastewater treatment updates, requirements that may be contested by inland officials who feel the cost would be excessive. Their arguments are “short-sighted” Basnight explains, because treated water moves from a river to an estuary and eventually into the sea. “Without the sea, there is no life,” he says. “Oceans don’t survive without the creeks, without the estuarine systems.”

Coastal ecosystems can feel the strain of the cumulative impact of the growth across the state. Basnight often is challenged to describe complex environmental changes in terms everyone can understand — crucial efforts in tight budget times.

“I have witnessed attempts to remove money for water quality projects,” says Basnight, who is credited with establishing the state’s Clean Water Management Trust Fund in 1996. The fund is the state’s only dedicated source of funding to preserve environmentally sensitive areas to ensure water quality. Such projects, he says, are not limited to the coast. “We shouldn’t have imaginary lines dividing the state,” he adds.

Despite his role on natural resource issues, Basnight refuses to be labeled. “I am not an environmentalist.’ You can’t stamp me,” he says. “I come with the independence of the Outer Banks.”

For example, he says, the state can step too far, even on environmental matters. “There must be value in every regulation,” he says, pointing out the possibility that regulations may have unexpected adverse effects on individuals or communities. “The government should be flexible,” he says.

Tides of Change

When Basnight was growing up in the 1950s, the Outer Banks featured a series of quiet fishing villages with scattered cottages. Even today you can hear a bit of his “hoi toider” accent that harkens to a time when the region was isolated from the rest of North Carolina.

His grandfather, Moncie Daniels, ran a general store and chaired the Dare County commissioners. His mother drew accolades as a veteran actress in “The Lost Colony” outdoor drama. Fellow cast member Andy Griffith remains a family friend. Basnight himself had small roles as a youngster.

A 1966 graduate of Manteo High School, he went to work in his father’s construction business that specialized in water and sewer lines. Now when he is not in Raleigh or on the road on state business, you can find Marc Basnight greeting customers at Basnight’s Lone Cedar Cafe, a restaurant run by his wife, Sandy, and his older daughter, Vicki. A younger daughter, Caroline, is a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

On weekends, he strides from table to table, calling locals by name and asking after their families, or making sure tourists have an enjoyable meal and plan to return to the Outer Banks. Sometimes folks make the long drive just in hopes of catching a few moments of his time.

The restaurant features local seafood, and his extended family includes folks in the fishing and restaurant businesses. The cafe even boasts its own soft-shell crab operation out back that serves as a demonstration project. The shedding technology was introduced to the Outer Banks by North Carolina Sea Grant fisheries specialist Wayne Wescott, who grew up in Manteo with Basnight.

Basnight knew early on that the coastal communities had a direct link to the universities — his father-in-law, Hughes Tillett, was the first Sea Grant extension agent in North Carolina.

Basnight never earned a college degree, but his legislative focus on education earned him an honorary doctorate of law from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a leadership award from the North Carolina State University Alumni Association.

Many in Dare County will recall that Basnight was a leader in planning for local celebrations for the nation’s bicentennial in 1976. A year later, he was named to the N.C. Board of Transportation. While he disputes stories that he wore sandals to his first board meeting, he was not a suit-and-tie kind of guy at the time.

When a cousin, Melvin Daniels, stepped down from his state Senate seat, Basnight was tapped to run. In his first attempt at public office in 1984, he won the seat representing eight northeastern counties and portions of three others — an area compared to the size of the state of Connecticut. While Dare County has seen economic growth through tourism, several counties in the northeast have struggled to maintain their population and to seek out new business or industry.

As chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee in the early 1990s, Basnight faced a $1 billion shortfall in the state budget. His leadership through those difficult times was rewarded when he was elected president pro tempore in 1993 — and he holds the distinction of being North Carolina’s longest-serving legislative leader in either chamber.

Visions of Leadership

Basnight insists that he is one part of a pool of decision-makers in state government. “I never get up in the morning and feel I know more than my neighbor — and that neighbor may be anyone in the state of North Carolina,” he says.

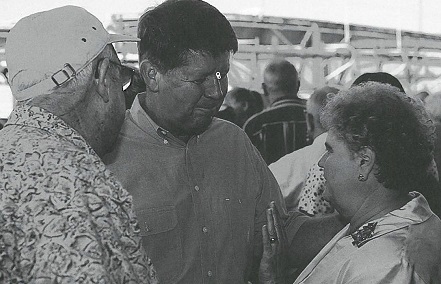

Profiles last year in Raleigh’s News & Observer and Metro Magazine describe Basnight as a study in contrast — a shrewd politician, yet also a down-home friend to many. He regularly stops by country stores to chat, but he also can help focus political fundraising for specific races.

“Basnight gets results, in part, because he is a consensus builder, carefully cultivating Democratic caucus members and soliciting their views and sharing power,” the N&O story says.

But consensus is not always achieved. Basnight acknowledges there are times where he must sort through arguments where each side offers valid points. “Every politician has difficult decisions to make. And there is someone out there — sometimes a long-time friend — who disagrees,” he says.

“I have to make tough calls — and the call often becomes final from where I am at,” he says. “That can be an uncomfortable position.”

He also must weigh the various requests or suggestions that come to his office. “Sometimes folks call and say, ‘Marc, you know you could do something.’ And I probably could, but that would change the way I govern.”

The disagreements in the legislature are like those in a family, he says. Some blow over in a week. Others could lead to a divorce. “In our process, in our republic, our democracy, you have to do what you truly believe is right,” he says.

Sometimes that means a change in position. “If I flip-flop, so be it,” he says, adding that he refuses to sign pledges that have become popular in some political circles.

“I want the freedom to make the right choice,” he adds, noting that new facts may come to light during the course of a debate. “I want to remain where I can change my mind,” he says.

Innovative Partnerships

Among his coastal efforts over the years, Basnight takes particular pride in the N.C. Fishery Resource Grant Program (FRG) the first state program to provide research funds for projects developed by individuals in the fishing and seafood industries. He cites a positive impact along the North Carolina coast, where the residents use intuition and experience to propose projects to define what is happening in the waters they know so well.

North Carolina Sea Grant administers the $1 million-per-year FRG program that encourages partnerships between the fishing communities and university researchers. Those partnerships are important, for they recognize the knowledge of people who have worked the waters for generations, Basnight says.

“We can’t succeed in our future without understanding our past,” he adds. “If there is one significant finding, it all would be worth it.”

The program has funded a wide variety of projects since it was founded in 1994. Project results have been considered during discussions of fishery management options — including several of the species-specific fishery management plans. FRG researchers often are asked to share their findings with the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission. An FRG report on small-mesh gill nets in Currituck Sound was presented in December 2001, as the commission was considering the striped bass management plan.

National Fisherman featured a cover story on Pamlico County students who have tested bycatch reduction devices in FRG-funded projects. Currently, 11 crabbers and a graduate student are working together to reduce mortality in the soft-shell or peeler crab industry. And processors are working on formulas for value-added seafood products that consumers and chefs can prepare with ease.

FRG was the model for a grassroots fishery research program in Virginia, and other states are considering similar programs.

“We have been able to demonstrate that when fishing communities work with scientists, we get the best from both worlds,” says Ronald G. Hodson, North Carolina Sea Grant director.

In 2000, Basnight spearheaded the establishment of the state’s Blue Crab Research Program. Administered by Sea Grant, the program focuses $500,000 each year on researching the state’s leading commercial fishery. And again, there is an emphasis on teaming crabbers with academics.

Even in tight financial times, Basnight sees a need to learn more about the blue crab fishery in North Carolina, especially as Chesapeake Bay stocks have declined markedly. “How do you find out unless you do the research?” Basnight asks.

And when it comes to fishery research, Basnight sees additional needs.

Encouraging Oysters

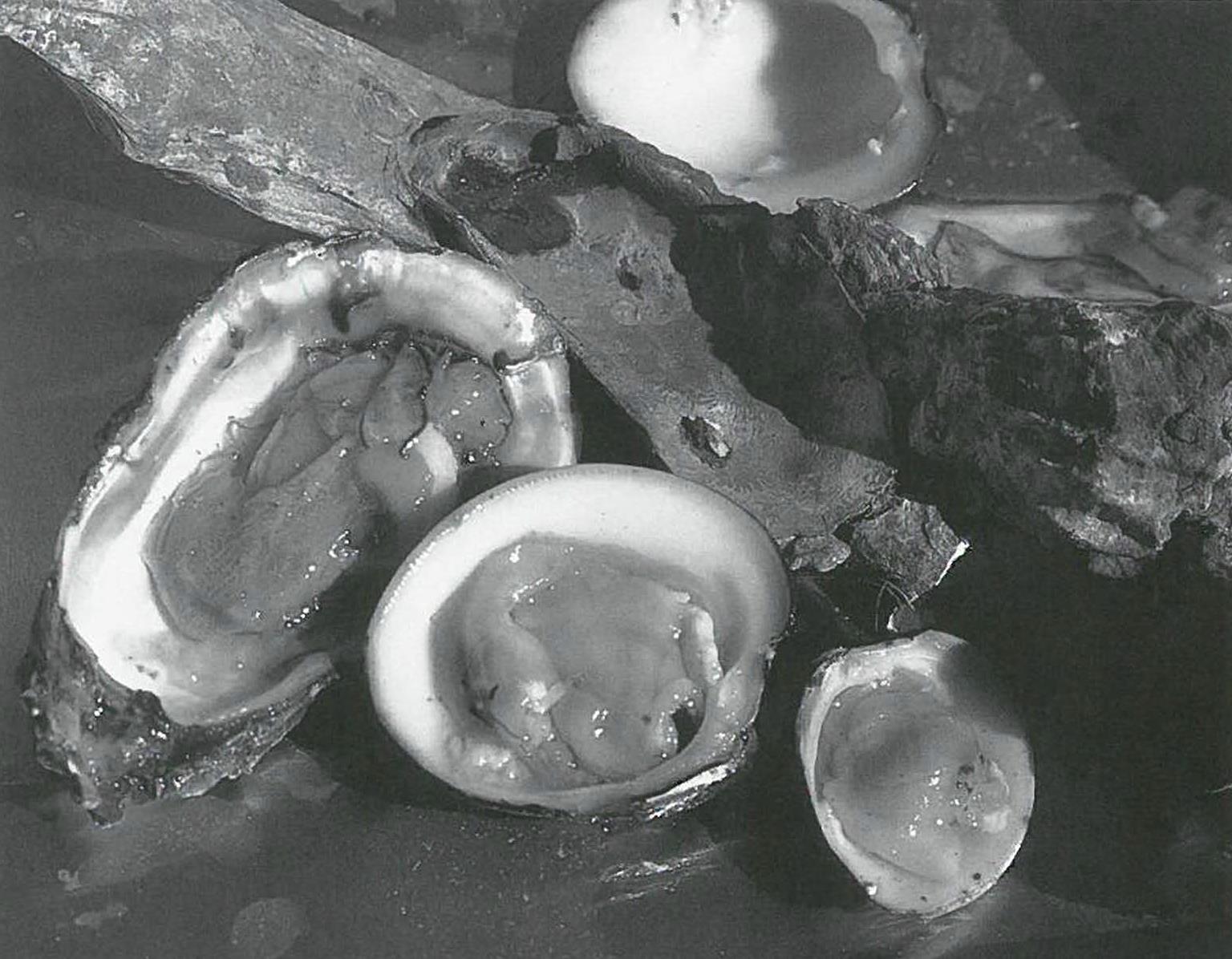

“We’ve got to do something on oysters,” Basnight says. “The biggest dream I have is to put oysters back into the estuaries of North Carolina — like they were before.”

In the early 1900s, North Carolina was known for its oyster harvests. Now, more than 90 percent of the oysters sold or shucked here come from the Gulf of Mexico, according to the N.C. Shellfish Sanitation Section.

For communities that still have oyster festivals, that means most of the oysters served are not local. Many areas of coastal waters are closed to shellfish harvesting because of pollution.

Initial steps could include creating new oyster reefs with wetland mitigation funding from state transportation projects in the coastal area, Basnight suggests. Or efforts may be funded with federal grants, such as an oyster reef project at Nags Head Woods.

The value of oyster reef restoration is three-fold, Basnight explains. Oysters filter water, thus enhancing water quality in the vicinity of the new reefs. The reefs also provide habitat areas for important commercial and recreational fish species. And eventually, the oysters may become stew, fritters or a steamed delicacy.

“Imagine what we could do,” he says, looking out a window in his restaurant, across the Roanoke Sound to Shallowbag Bay and the town of Manteo. “When I grew up, you’d catch all you could. Now there aren’t any in that bay that I grew up on — and I am only 54 years old.”

Oysters are not a new topic for Basnight, who was a force behind the formation of the N.C. Blue Ribbon Advisory Council on Oysters. The 19-member council — which included commercial harvesters, mariculturists, biologists, market specialists, processors, fishery scientists and social scientists — offered a report in October 1995.

The council’s major recommendations included efforts to encourage mariculture by revising some laws and procedures, as well as efforts to restore or protect existing reefs. Other efforts would be to protect water quality, to provide environments where oysters could be harvested for consumption, and to support an industry-based seafood council to increase consumer demand for oysters and other seafood.

Basnight’s vision includes communities being able to market oysters in terms of distinct flavors and products. “We must reverse the decline,” he says of the current status of oyster stocks. “We are going to have to accelerate these efforts,” Basnight says. “We are not doing nearly enough.”

This article was published in the Winter 2002 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: