On a recent July morning in Brunswick County, carefree locals and tourists head for their favorite barrier island beaches. Most are unaware of the dozens of emergency workers scrambling to “hurricane disasters” enfolding at sites in nearby Shallotte and Grissettown: A Category 3 hurricane has leveled two buildings — trapping, injuring or killing the occupants.

Orchestrated by Brunswick County Emergency Services (BCES) Director Randy Thompson, the training exercise is one of the largest of its kind in the county. It brings together nearly 200 emergency workers from dozens of agencies from as far away as Fayetteville and Greenville. Local Boy Scouts and other volunteers play-act as victims in the mock disaster.

Responders set up a command center, conduct search and rescue operations, triage survivors, evacuate mass casualties to Dosher Memorial Hospital in Southport and secure the sites.

Such an exercise is more than a dress rehearsal, Thompson says. It’s a way to evaluate the county’s comprehensive hurricane response plan, hone procedures and skills and test an array of new equipment and technologies in a controlled situation.

Still, Thompson knows that natural disasters are never scripted. That’s why emergency managers prepare for the worst — but hope for the best.

Special Needs Community

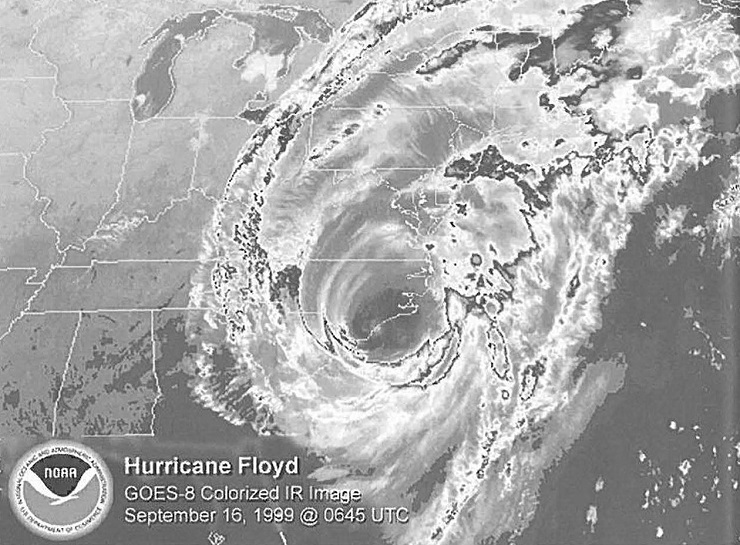

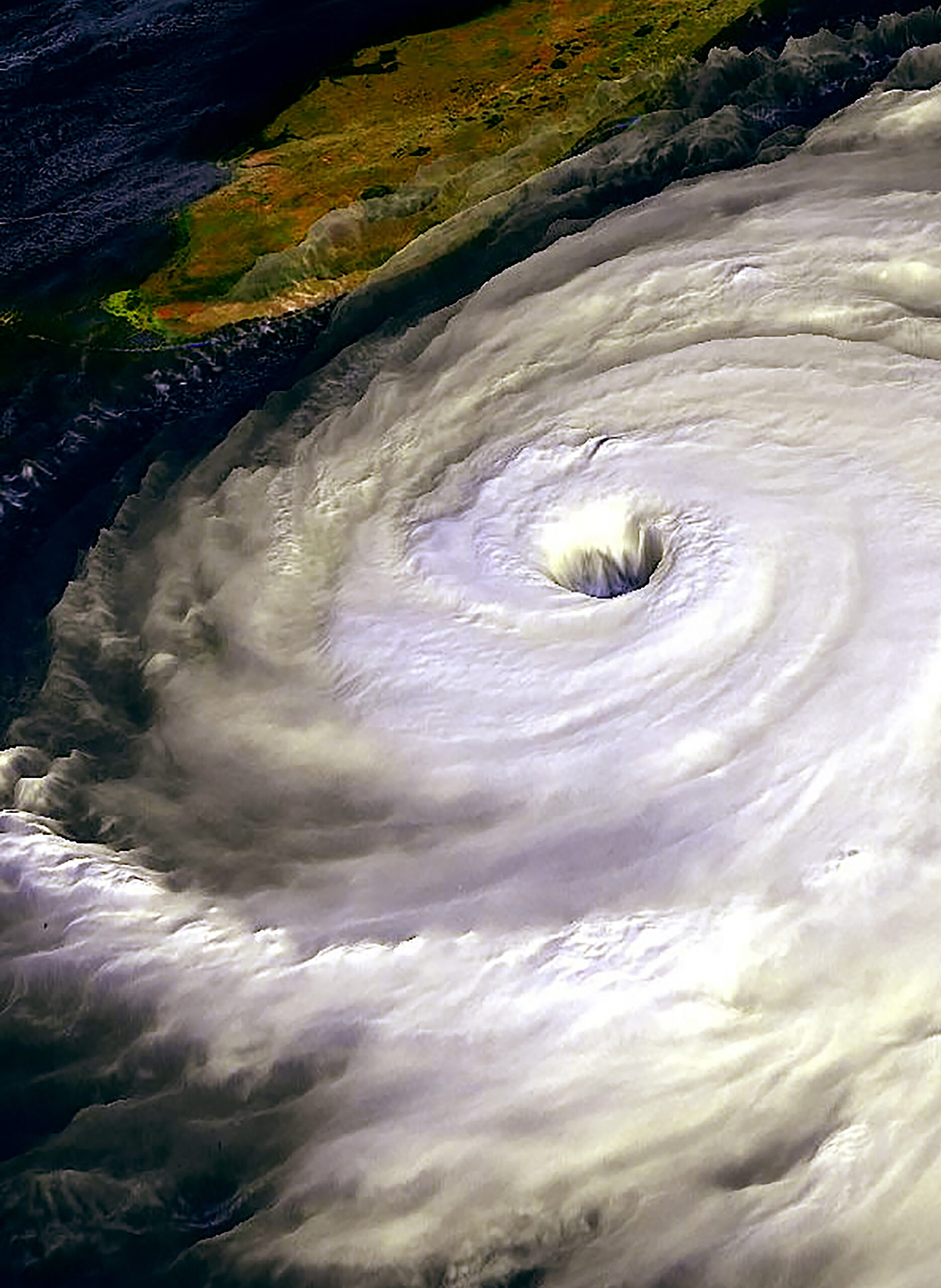

Indeed, Hurricane Floyd was a “worst-case scenario,” says Thompson, who moved to Brunswick from Wake County Emergency Services in 2000. He recalls that Floyd prompted emergency management professionals and volunteers from across the state to assess readiness, response and resources — all stretched beyond capacity by the magnitude of the 500-year flood event.

Clearly, Floyd underscores the need to address evacuation procedures for special needs citizens before a disaster strikes. Brunswick, Carteret, Columbus, Dare, New Hanover, Onslow and Pender counties had special needs registries in place by 1999 — before Floyd hit.

However, unprecedented growth in many coastal counties during the past decade keeps emergency services personnel busy updating records and getting the word out about the registry through media, churches and community organizations and local hurricane forums, explains Brian Watts, director of Brunswick’s Emergency Management Services Division.

Special needs registration enables emergency workers to identify individuals, their locations, their medical situation, their mobility (or lack of) and their access to (or lack of) transportation. Residents can go to individual county Web sites for a link to emergency services’ home page and special needs registries.

Since January, Brunswick County paramedics have been visiting 295 people now on the county’s registry to assess changes in individual situations and learn more details about medical needs. Each registrant receives a photo identification card, bar-coded with vital information for medical personnel to scan instantly in future emergencies.

“We usually see people at the worst time in their lives. Knowing we are prepared for their situation means they are more apt to stay calm in the face of an emergency evacuation,” Watts says.

Silver Lining

In recent years, U.S. Department of Homeland Security grants have provided silver linings to storm clouds by helping many coastal counties beef up funding for disaster preparedness and response resources.

Thanks to such a grant, BCES put a Mobile Mass Evacuation Bus into service this summer — in time for the simulated hurricane disaster exercise. The bus, fully equipped with a nurses’ station, communications, medical supplies and stock ambulance equipment, is capable of moving a large number of individuals to safety at once. It can be configured to hold 20 patients on stretchers and 10 in wheelchairs, or as many as 30 patients in wheelchairs.

In an emergency mass evacuation, the bus would head to Odell Williamson Auditorium at Brunswick Community College (BCC) — the designated coordination center for evacuees with special needs and their caregivers. In addition to the mass evacuation bus, BCES also would deploy school buses, ambulances and accessible vans to transport homebound patients to BCC.

“The important thing is that we know where the special needs people are located in our county and that we have worked with the Brunswick County Schools’ transportation folks to plan the best bus routes,” Watts notes.

At the center, medical emergency personnel register and triage each evacuee and assign resources according to specific medical requirements — from IV and oxygen to wound care and assistance with injections. Precious time is saved for those already on the special needs registry.

“We are excited to be a partner with emergency services to provide a medical support shelter for mass evacuations,” says Jerry Thrift, BCC vice president for operations. “It’s an innovative and wonderful operation — but one that we hope we won’t ever have to use.” The center will include a food unit and accommodate pets for relocation with their special needs owners.

If necessary, patients would be prepared for transportation from the center to an inland shelter — either Robeson County Community College or Johnston County Community College depending on road conditions.

In addition to the BCC site, BCES partners with local, state and federal organizations to operate emergency shelters at other locations in the county, including a co-location site for people and their pets at West Brunswick High School. In an emergency situation, officials will assess the need for opening additional co-location sites.

Crucial Communications

Storm preparation requires constant communication and collaboration with federal and state emergency management personnel, local municipalities and EMT units, Thompson says. Since Hurricane Floyd, improved technology better enables coordination among counties and towns from five to 10 days before the storm approaches the North Carolina coast.

State and local emergency personnel rely on NC-FIRST that uses information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS), National Hurricane Center and the State Climate Office of North Carolina. NC-FIRST helps them access and interpret weather data so they can make better decisions during weather emergencies. NC-First was developed by the Renaissance Computing Institute (RENCI) — a collaborative venture of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina State University, Duke University and the state of North Carolina.

Throughout the warning and watch periods, local, state and federal officials conduct conference calls using WebEOC, a Web-based crisis information sharing system for emergency managers and first responders. WebEOC enables coordinated decision making — including issuing evacuation declarations. Mandatory evacuation declarations come from local municipalities in collaboration with state officials.

“Timely communication is the key to getting life-saving information to the public and directing them to designated shelters,” Thompson says.

Time lines for evacuation from barrier beach communities vary according to circumstances. Bald Head Island depends on ferrying evacuees to the mainland and, therefore, requires much longer pre-storm evacuation timelines. Sunset Island’s swing bridge closes to traffic with 40 mph winds because bridge tenders must secure it in place. Bridges from other barrier islands are closed to traffic when wind levels reach 45 mph.

Monitoring Evacuation Routes

Emergency officials’ greatest concern is directing the public to the safest evacuation route. And that can be tricky in low-lying Brunswick County.

“Our greatest fear is flooded roadways,” Thompsons says.

To address that concern, RENCI developed and installed flood sensors at eight flood-prone sites along U.S. 17, NC 133, NC 87, NC 211 and Ocean Isle Beach Road.

Data is sent to NWS through RENCI’s NC FIRST program. The system could reduce the impacts of floods by providing early information about these critical evacuation routes. The information will allow emergency workers to re-route evacuation routes and rescue efforts. Highway message board signs and media would post flood warnings and help direct evacuees to safer routes; light towers and pumps to move water might also be deployed.

In the past, flood monitoring depended on someone observing water levels and reporting findings by radio, Thompson points out. “The RENCI flood sensors will help us better prepare for flood conditions. More people and few evacuation routes present a challenge for evacuating our people, especially those with special needs,” he says.

After the Storm

The days after a major tropical storm can be eerie, Thompson says. People may feel cut off from the rest of the world when they are faced with downed utilities, trees and construction material.

“Debris is a secondary hazard of storms,” he adds. It can be a public health hazard, clog roadways and hide downed electric lines.

Along with the hazard factor, he says, a focus on debris and destruction may be harmful to the public’s psychological ability to “come back” after a disaster.

A footnote to the rapid response strategy: First, Brunswick’s integrated hurricane plan established contracts for debris removal long before the start of hurricane season. Second, Brunswick County’s warehouse facility has a season’s supply of water, MREs, sandbags — and brooms, mops and bleach for homes and businesses.

Comprehensive, integrated planning efforts have increased ability of coastal counties to share information and resources, Thompson says. And, those who allocate funding at local, state and federal levels respect the work of emergency professionals and do their best to provide the resources needed to protect all citizens.

This article was published in the Autumn 2009 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: