A battle cry is being sounded to combat a serious ecological threat to the state’s biodiversity — invasive plants. Unchecked, invasive plants threaten crops and timberland, as well as open land and water resources.

It’s estimated that control costs and losses due to invasive plants in the United States approach $50 billion a year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Invasive plants are non-native or exotic plants that aggressively spread and displace native plants — significantly altering habitats and ecosystems.

Early detection and rapid response are key components of a strategy to neutralize the enemy, says Randy Westbrooks, invasive species specialist with USGS Coastal Plain Invasive Species Project Office in Whiteville. Westbrooks is helping to spearhead a multifront assault on the establishment or spread of invasive plants across the state.

“We want to tap into networks already out there — from professional land managers and park rangers to amateur volunteer naturalists — and ask them to multitask,” Westbrooks says. In other words, while they are walking trails or paddling canoes, they also could be looking for invasive plants.

Representatives from state and local agencies, nonprofit environmental organizations, industry and academia took the first step toward forming “a coordinated framework of interagency partners” this summer. Participants of this train-the-trainer workshop now are training others in their organizations to become engaged in the invasive plant identification and reporting process.

“We see this as an Amway approach for ecology preservation — each one teach one,” says Rick Iverson, state weed coordinator for the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. “We need a lot of partners to become familiar with the threats.”

The goal is to establish an N.C. Early Detection Rapid Response System, or EDRR, for invasive plants in order to “connect the dots” among a host of local, state and federal agencies; partner groups; and volunteer conservation-minded citizens, says Iverson, who also serves as president of the citizen-based N.C. Exotic Pest Plant Council.

A state initiative would become part of the developing National EDRR System — an important second line of defense against invasive plants; the first being federal efforts to prevent unwanted introductions at U.S. ports of entry, explains Westbrooks.

EARLY DETECTION PAYS OFF

Although federal and state regulators seek to control plants officially listed as noxious weeds, not all invasive or exotic plants have made those lists. Some plants introduced legitimately into the marketplace for their ornamental, food or fiber value, later may exhibit less-than-wanted qualities. Others may arrive here as hitchhikers in ballast water or as seeds attached to cargo, distributed by wind, or deposited in bird or animal droppings. Many remain under the radar until they become problematic.

Beach vitex is one plant that went from being touted as a beach dune builder to being a recognized dune habitat destroyer in a few short years. South Carolina turtle volunteer Betsy Brabson is credited for first sounding the alarm in 2003 when hatching turtles became entangled in beach vitex. She contacted Westbrooks, who organized a symposium for various stakeholders to address the proliferation of beach vitex.

Brabson’s early detective work paid off. A grant from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service funded the Carolinas Beach Vitex Task Force, enlisting the help of volunteers who routinely document sea turtle and shorebird nests to look for beach vitex sites. The educational effort included distribution of beach vitex identification cards that North Carolina Sea Grant’s Barbara Doll helped to develop.

“Citizens have proven to be very effective at early detection of new invasions by exotic species as was demonstrated in the late ’80s and early ’90s when zebra mussels showed up in the Great Lakes. Citizens armed with the wallet-sized identification cards that include pictures and diagrams can readily identify species and alert state and local officials about new locations,” Doll says.

Soon, beach vitex was placed on the North Carolina noxious weed list and an approved chemical eradication program was implemented. “The eradication program is showing great signs of success,” says Melanie Doyle, North Carolina coordinator of the Carolinas Beach Vitex Task Force. “And of course, no one is planting beach vitex because no one is allowed to sell it anymore. Happily, sea oats — some planted and some naturally rebounding — are swaying atop the dunes.”

Doyle adds that the task force is vigilant along the coast, reminding town officials, extension specialists and homeowners to be on the lookout and report any resurgence. “We feel comfortable that there are no other large colonies out there, and continue looking for any small plants that may emerge from previously treated areas.”

The eradication of giant salvinia in North Carolina is another testimony for early detection and rapid response. The nuisance aquatic weed has been conquered here in less than a decade, Iverson reports. But there are other plants headed this way that need the same kind of proactive strike.

DID SOMEONE SAY KUDZU?

To Westbrooks, cogongrass is Public Enemy Number One. This federally noxious weed is considered a high threat on all continents except Antarctica. South Carolina has 11 sites being managed. So, the battle line is being drawn at the state line.

Called the “perfect weed,” this perennial grass grows up to six-feet tall; thrives in a variety of habitats; and is tolerant of shade, sun, high salinity, drought, flooding, mowing and fire. It out competes native plants and drives out native wildlife. It affects forests, pastures, roadways and wetlands across most of the Southeast — so far, except North Carolina. Added to its bad habits, cogongrass poses a serious fire danger, Westbrooks notes.

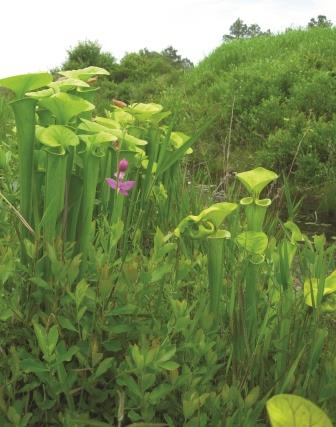

The “border patrol” also needs to be on the lookout for crested floating heart, an herbaceous aquatic plant that is threatening to choke the life out of South Carolina’s Lake Marion. The plant was introduced as a water garden plant, but soon escaped its cultivation boundaries and has spread to waterways, canals, ponds and lakes. Alarmingly, says Iverson, plant fragments can be transferred from lake to lake on boat motors and trailers — or seeds can ride on wind and flowing water.

Mile-a-minute vine also is high on Iverson’s checklist because it already has presented itself as a problem in neighboring Virginia. “Recently, a botanist reported seeing it in Alleghany County,” says Iverson, who will take a closer look to determine the extent of its presence.

Like kudzu, mile-a-minute grows in open and disturbed areas, forest edges, moist thickets, wetlands, stream banks and the roadside.

Why all the fuss about managing or eradicating invasive plants? “Well, think ahead in ecological time to what North Carolina would be like in 500 years if we allow things like kudzu to win,” Westbrooks says. “This is a call to arms for those who care about biodiversity and how we establish an ecological protection ethic.”

FACING FUTURE CHALLENGES

Experts agree that building and sustaining a state EDRR system to address current and future invasive plant threats will depend on educating, training and inspiring people to join forces.

The next generation of invasive plant fighters are likely to come from Southeastern Community College, where Rebecca Westbrooks heads the environmental science and technology program. She introduces students to invasive plant issues in a variety of settings.

Her students learn that invasive plants constitute a major ecological problem and get hands-on training via a Student Weed Stopper Program on campus. “Survey where you are and report what you see,” she urges students.

Reaching beyond the campus, she and her husband, Randy Westbrooks, designed an online Invasive Plant Management Program. Completion of the course enables students to achieve either an associate’s degree in environmental science technology, or a certificate in invasive plant management.

For the past three summers, the Westbrooks have collaborated to bring high school students from around Columbus County to a weeklong Summer Science Enrichment Camp. Sponsored by a grant from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, students split their time between the community college campus and Lake Waccamaw State Park. They learn about invasive plant species through lectures and hands-on field experiences conducted by experts from across the state and country.

Soon, the Westbrooks and a handful of students will embark on an important survey that will follow the Waccamaw River from its headwaters to Georgetown, S.C. They will locate and record all invasive plants they encounter. — P.S.

To learn more about getting involved in the North Carolina EDRR initiative, contact Randy Westbrooks at: rwesterbrooks@ecjr.com or Rick Iverson at: rick.iverson@ncagr.gov. For additional information about the N.C. Exotic Plant Pest Council, go to: www.se-eppc.org. To learn about the programs at Southeastern Community College, go to: www.sccnc.edu.

This article was published in the Autumn 2010 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: