For decades, readers of Coastwatch have been devouring content about North Carolina’s sharks. Here’s a collection of 12 interesting tidbits from our partners at NOAA that includes information about sharks around the globe.

1

Sharks don’t have bones. Sharks use their gills to filter oxygen from the water. They are a special type of fish known “elasmobranch,” which translates as “fish made of cartilaginous tissues” — the clear gristly stuff that your ears and nose tip are made of. This category of fish also includes rays, sawfish, and skates. Their cartilaginous skeletons are much lighter than true bone, and their large livers are full of low-density oils, helping them to be buoyant.

Even though sharks don’t have bones, they still can fossilize. As most sharks age, they deposit calcium salts in their skeletal cartilage to strengthen it. The dried jaws of a shark feel heavy and solid, much like bone. These same minerals allow most shark skeletal systems to fossilize quite nicely. The teeth have enamel, so they fossilize, too.

2

Most sharks have good eyesight. Most sharks have fantastic night vision, and they can see colors. The back of sharks’ eyeballs have a reflective layer of tissue called a tapetum, which helps sharks see extremely well with little light.

3

Sharks have special electroreceptor organs. Sharks have small black spots near the nose, eyes, and mouth. These spots are the ampullae of Lorenzini — special electroreceptor organs that allow the shark to sense electromagnetic fields and temperature shifts in the ocean.

4

Shark skin feels exactly like sandpaper, because it is made up of tiny teeth-like structures called placoid scales, also known as dermal denticles. These scales point towards the tail and help reduce friction from surrounding water as sharks swim.

5

Sharks can go into a trance. When you flip a shark upside down, it enters a trancelike state called “tonic immobility.” This is why you often see sawfish flipped over while NOAA scientists are working on them in the water.

6

Sharks have been around a very long time. Based on fossil scales found in Australia and the United States, scientists hypothesize sharks first appeared in the ocean around 455 million years ago.

7

Scientists age sharks by counting the rings on their vertebrae. Shark vertebrae contain concentric pairs of opaque and translucent bands. Scientists can count band pairs like rings on a tree and assign ages to sharks based on the count. However, researchers must study each species and size class to determine how often the band pairs are deposited, because the deposition rate may change over time.

8

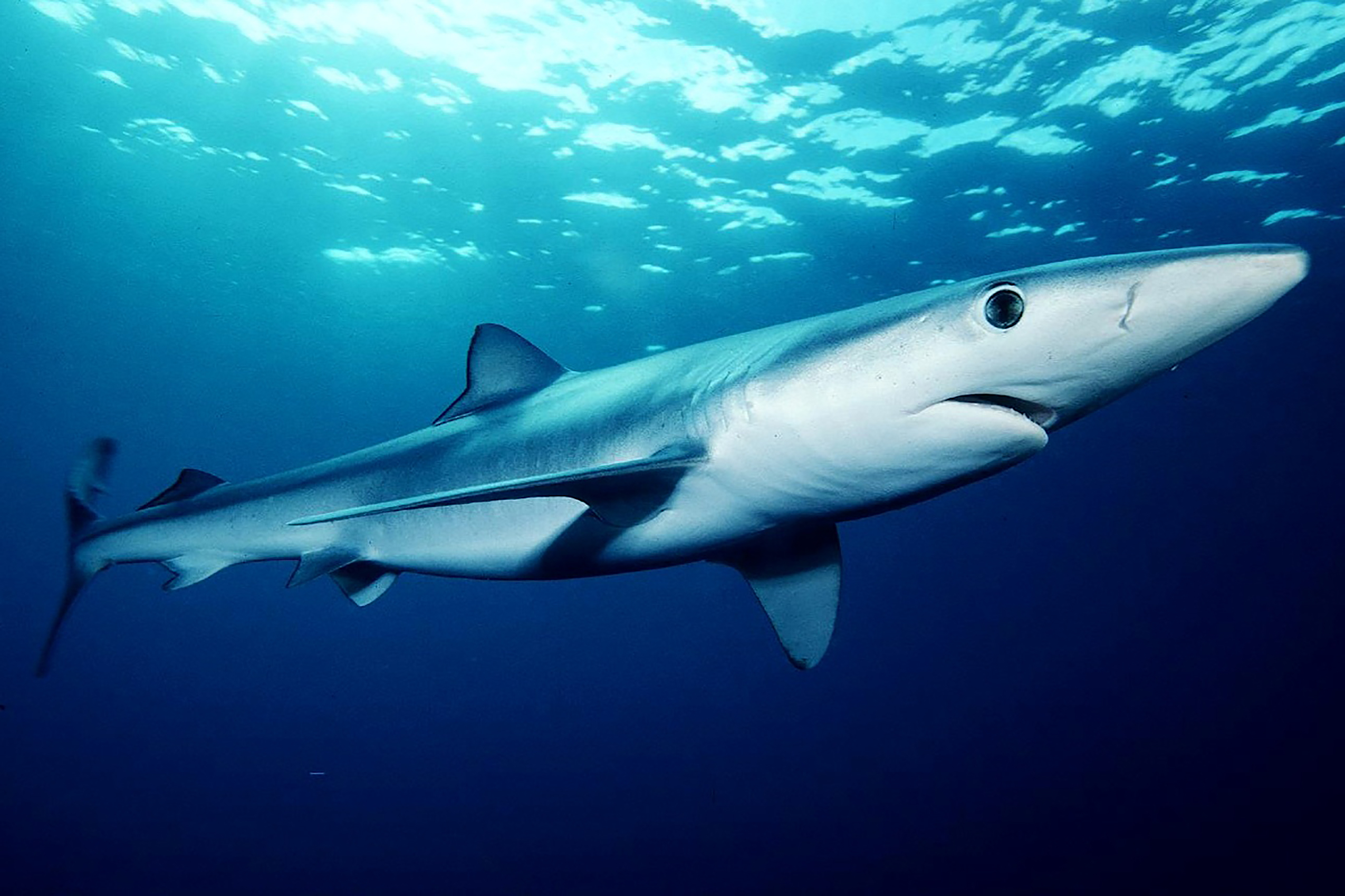

Blue sharks are really blue. The blue shark displays a brilliant blue on the upper portion of its body and is normally snowy white beneath. The mako and porbeagle sharks also exhibit a blue coloration, but not nearly as strikingly as a blue shark. Most sharks are brown, olive, or gray.

9

Each whale shark’s spot pattern is as unique as a fingerprint. Whale sharks are the biggest fish in the ocean. They can grow to 40 feet — and weigh as much as 40 tons, by some estimates. Basking sharks are the world’s second largest fish, growing to as long as 32 feet and weighing in at more than five tons.

10

Some species of shark have a spiracle that allows them to pull water into their respiratory system while at rest. Most sharks have to keep swimming to pump water over their gills. A shark’s spiracle is located just behind the eyes and supplies oxygen directly to the eyes and brain. Bottom dwelling sharks, like angel sharks and nurse sharks, use this extra respiratory organ to breathe while at rest on the seafloor. Sharks also use the spiracle for respiration when eating.

11

Not all sharks have the same teeth. Mako sharks have very pointed teeth, while white sharks have triangular, serrated teeth. Each leave a unique, tell-tale mark on their prey. A sandbar shark will have around 35,000 teeth over the course of its lifetime.

12

Different shark species reproduce in different ways. Sharks exhibit a great diversity in how they reproduce. There are oviparous (egg-laying) and viviparous (live-bearing) species of shark. Oviparous species lay eggs that develop and hatch outside the mother’s body with no parental care after the eggs are laid.

adapted from NOAA’s “12 Shark Facts that May Surprise You”

lead photo: sand tiger sharks, courtesy of NOAA

- Categories: