Sixty Miles Off-Shore

A First-Hand Account of Research on the R/V Palmetto

A Sea Grant fellow shares his experience aboard a science vessel — deploying traps, analyzing fish, and acclimating to life on the Atlantic.

The trap glided to the ocean floor, enveloped in a veil of dim sunlight. A soft thud and a wispy cloud of sand marked the end of a nearly 200-foot descent beneath the Atlantic surface to a seemingly extraterrestrial landscape.

I sat and watched in awe as the trap became shrouded in a city bustling with everything from crowds of curious vermilion snapper and triggerfish to wandering hogfish and wary grouper. I was watching what I call “fish film” — a compilation of underwater videos collected from traps deployed during my reef fish surveying experience aboard the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources’ R/V Palmetto.

As Sea Grant’s South Atlantic Reef Fish Extension and Communication Fellow, I conduct outreach throughout the coastal Southeast, communicating reef fish science and best fishing practices to a host of fisheries stakeholders. This work involves the snapper grouper complex, a federally managed fishery consisting of 55 species ranging from golden tilefish to Atlantic spadefish. In many ways, I act as the liaison between research, management, and the fishing industry.

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SC DNR) schedules their research in different segments or “legs.” I volunteered for a 10-day-maximum trip over a 12-day window in September. Unfortunately, hurricane season limited this leg to five days.

I first boarded the vessel late on a Monday night (11:00 p.m., to be exact). After crew introductions and a safety briefing, I headed down to the bunk room, climbed into my top bunk, and slept through the long, slow trek to the study site — a marine-protected area over sixty miles off the coast of South Carolina.

Scientific crews operate on 12-hour shifts during these legs, and I was slated to work a noon to midnight shift on the first day, which allowed me to hunker down in my bunk through much of the morning. However, being an excited rookie, I was eager to see the morning crew in action on my first day.

Chevron Traps and Thrashing Fish

As a noon-to-midnight shift worker, I typically would start around 10:00. I would wake from my top bunk (of three) and precariously jump down to the floor of the dark bunkroom, being careful not to wake the other researchers. Feeling my way out of the room, I would clamber up the lit stairway to the main living space. I would put on my waterproof work boots, lather up in sunscreen, and head outside to watch the morning shift at work.

Sometimes, I joined them during downtime and put out trolling rods, dragging bait or lures off the stern. During my research leg, crew members caught several barracuda and brought a rogue blackfin tuna boatside. I also saw a sailfish slash through some sardines that were schooling by the boat. After a quick morning trolling session, I would venture back to the galley for lunch at 11:30. Dinner was usually at 5:30.

On my first day, operating on less-than-ideal sleep, I clumsily climbed upstairs and ventured out onto the observation deck. Chevron trap sampling had just begun.

Chevron traps are essentially wire mesh traps shaped like a “V,” with the inside notch of the “V” serving as a one-way funnel. It’s a scaled-up version of a minnow trap. Fish swim into the funnel to access bait but have trouble swimming back out.

On this trip, the survey crew baited the traps with menhaden (a widespread local baitfish), harnessed the traps with GoPro cameras, and attached the traps to identification buoys.

When deploying the traps, the captain and chief scientist give directions to the onboard crew, noting the distance to the upcoming drop zone. A horn over the intercom signals crew members to toss the trap overboard and feed the buoy line off the stern. Each trap sits for 90 minutes before a crew member retrieves it with a hydraulic pulley system.

After the crew swings a trap back onto the deck, they remove the GoPros and lines and then open it, releasing the catch. I had the pleasure of completing this task on several occasions. While others held the trap off the deck, I crouched down and opened a bungeed trap door, releasing a fury of thrashing (and spiny) fish into a collection bin.

Each bin has a label corresponding with the trap and set number, and the crew immediately covers the fish in saltwater ice for analysis, or “work-up,” as the SC DNR team calls it.

Ear Bones, Dorsal Spines, and More

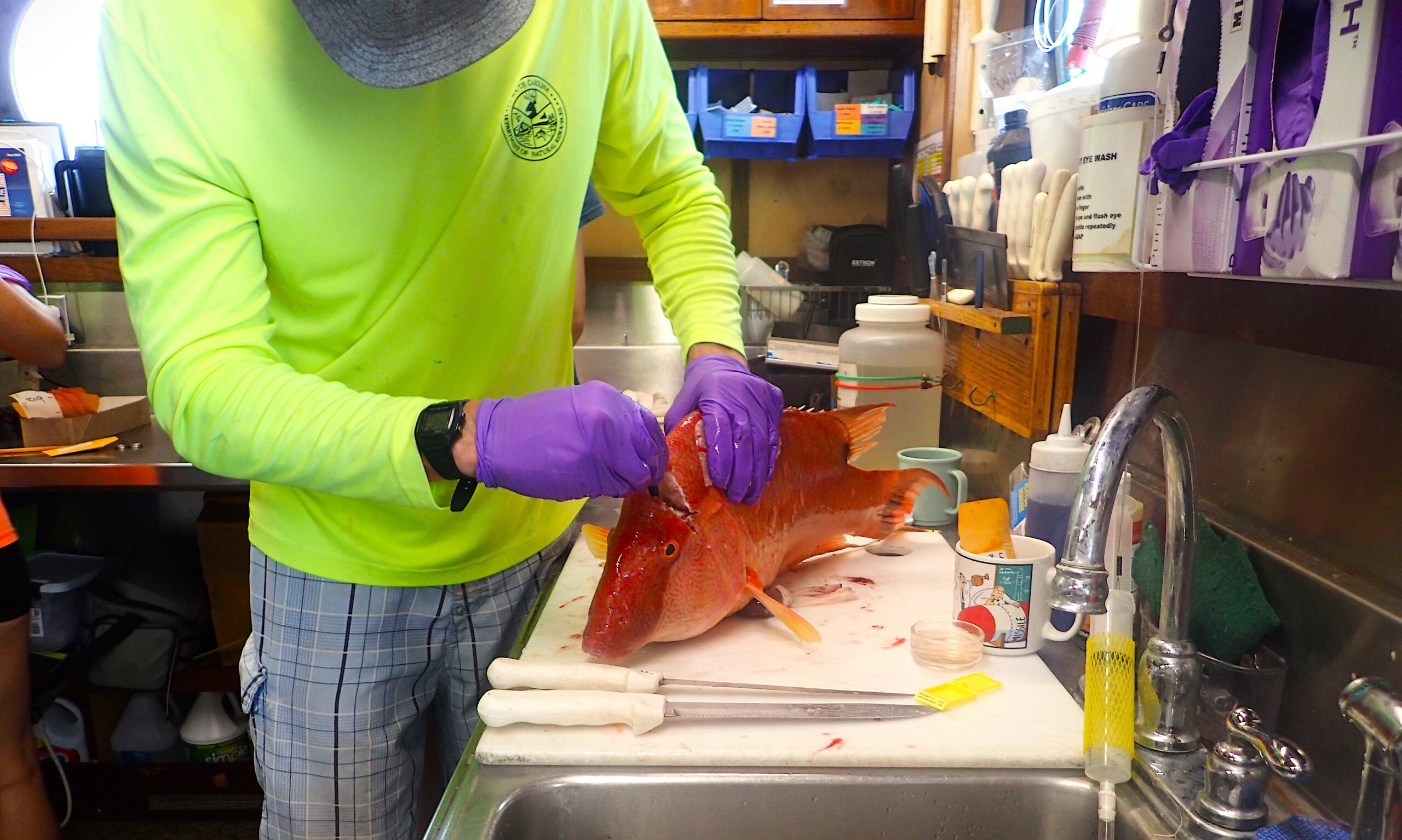

Fish work-up involves weighing by species and then using a magnetic measuring board linked to a computer. Crew members pre-select a species code and record each fish’s length. For some species, like red porgy, the crew keeps every fish for future analysis. For others, like vermilion snapper, they select 50% at random.

Biological sampling typically begins with otolith extractions. Otoliths are bony structures that are part of the inner ear. Similar to the otoliths in humans, fish otoliths help with balance — but, more importantly to the survey crew, fish otoliths have growth rings, much like trees. These rings help scientists determine each fish’s age and, in turn, ultimately estimate the overall age structure for a species’ population.

Although not as seasoned as some staff, I certainly processed my fair share of otoliths on this trip. Gray triggerfish were an exception. We extracted dorsal spines for this species to determine age with growth rings. Depending on the species of fish, we also harvested gonads, eyes, and muscle tissue samples for future analysis.

When the survey crew finishes processing fish for samples, the team transfers their fillets to the “donation cooler” for several local non-profit organizations to use as food for people and wildlife.

The Sea at Night

Toward the end of my shift, late at night, the boat captain would typically anchor over some reef bottom to allow the crew to drop in lines for entertainment and to collect fish that don’t as readily enter the traps. The survey crew collected data from these fish just like the fish from traps.

The Atlantic during the dark morning hours was a special experience for a marine science enthusiast like me. The ocean came to life with nocturnal critters dancing in the boat lights. I watched as rock shrimp, eels, squid, ctenophores, and flying fish flashed through the surface waters. In the several nights offshore, I did everything from netting a small flying fish to wrangling a nearly 200-to-300-pound dusky shark on hook and line before releasing it back to the depths.

I’d like to thank Tracey Smart, SC DNR’s chief scientist on the leg, as well as the crew, for their willingness to let a rookie like me work alongside them. It was an incredible experience living offshore and conducting hands-on reef fish research, and I look forward to drawing upon my surveying experience moving forward.

MORE

Coastwatch on sustainable fisheries and aquaculture

The popular Hook, Line & Science series for recreational fishers

David Hugo is the current recipient of the South Atlantic Reef Fish Extension/Communication Fellowship, which provides on-the-job education and training opportunities in reef fish extension and communication for an early-career professional in the southeast region.

- Categories: