The Untapped Resource: How Students Can Help Build Community Resiliency

As children learn through environmental education — and pass along what they discover to adults — the process equips young and old to take informed action.

“Nature can be destructive, as many of our coastal friends know well,” says Kathryn Stevenson, head of NC State University’s Environmental Education Lab.

Stevenson says that many children feel helpless, with climbing global temperatures, worsening extreme weather, and the increasing effects of plastic pollution and emerging contaminants. As a result, students at the coast and elsewhere need new ways to understand the environment around them.

“Environmental education is a way to help you figure out how to connect with nature in a positive way,” explains Stevenson, whose work has included several Sea Grant projects. “Then you can advocate for the health of the coastal ecosystem.”

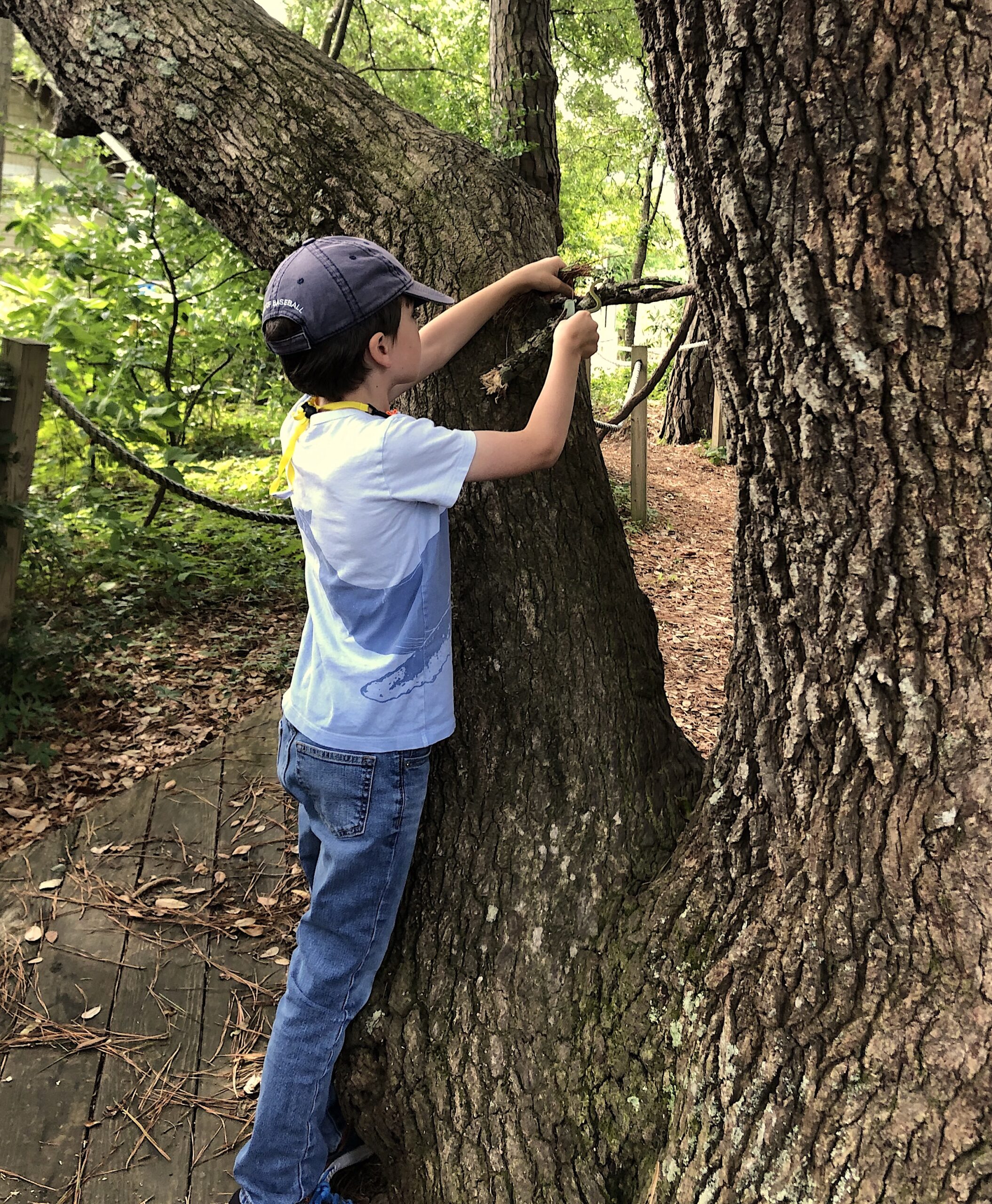

Environmental education takes place informal and informal learning settings, including summer camps and national parks. Activities allow students to take control of their own learning through exploration and hands-on activities. In outdoor settings and in classrooms, learners develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills by discovering how environmental systems work, as well as how and why urgent issues arise.

Stevenson has found that children form better relationships with the content they are learning, with their peers, and with themselves, when they feel empowered to contribute to their communities. When a group of children work together to find a solution to keep marine debris out of the water, for instance, they gain a sense of accomplishment and pride in their learning.

And, as students become more environmentally literate and understand the ecosystems around them, they become empowered to take informed action. This includes teaching their family and friends about their discoveries.

In fact, environmental education also encourages communication. Children or adults who go on a naturalist-guided hike want to tell their loved ones about their discoveries, helping to build their community’s environmental literacy.

KIDS HAVE LOUD VOICES

Stevenson’s lab studies what drives environmental literacy. The Environmental Education Lab isn’t filled with glass vials and pipettes. It tests how people, mainly children, respond to different experiences with nature and their communities.

It was an important discovery for the lab when Danielle Lawson’s 2019 doctoral project found that when children voice concern about climate change, their parents do, too. North Carolina Sea Grant provided funding for Lawson’s research.

“Kids have a say in their community,” Stevenson explains, “and adults listen to them in ways that we don’t typically see. Normally, climate change communications just polarize people more, but when information comes from kids it seems to mitigate that a little bit.”

Jenna Hartley, NC State University’s first NOAA Dr. Nancy Foster Scholar, wanted to see if Lawson’s findings meant that children could generate community-wide action. To create an engaging environmental education curriculum that they could test, Hartley and Stevenson teamed up with Liz DeMattia, head of the Community Science Team at the Duke University Marine Lab.

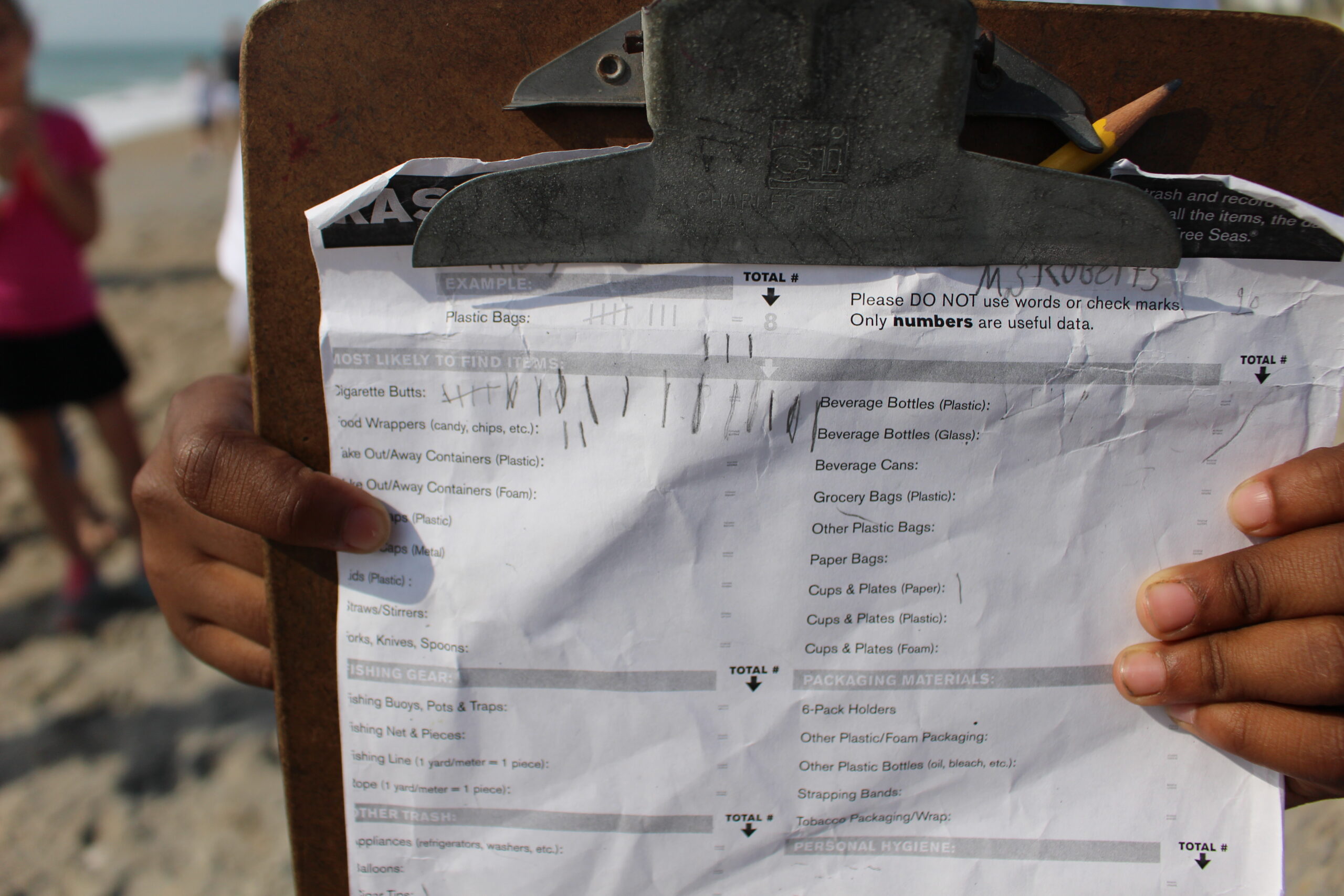

They hosted retreats at the Duke University Marine Lab for teachers across North Carolina who were enthusiastic about bringing community science into their classrooms. With funding in part from North Carolina Sea Grant, about 60 teachers from across North Carolina learned how marine debris affects communities by conducting beach clean-ups and trash audits. At the retreats, Hartley, DeMattia, and Stevenson also explored how students could use their enthusiasm and creativity to host community engagement projects that spread the message about what they learned. This enabled Hartley, who received her Ph.D. in 2022, to test how the students’ voices expanded beyond their immediate families and into their wider communities.

In addition to providing a brainstorming space, the retreats benefited teachers by connecting them with fellow teachers — an important opportunity, given how often educators feel isolated.

The students also clearly benefited from their teachers having attended the retreats; when the teachers returned, they were more equipped with materials and support to incorporate a science activity on marine debris into their class plans.

“Kids loved getting outside, picking up trash, and taking local action on the issue of marine debris,” Hartley says. “Their high levels of engagement created a positive feedback loop for their teachers, encouraging teachers to continue incorporating environmental education into the classroom.”

After having a blast picking up trash, the students’ enthusiasm carried into their community engagement projects, generating art shows, performing plays, conducting slam poetry nights, and formally presenting their public service announcements at local town hall meetings.

Through survey results before and after the teachers provided the curriculum to the students, the lab concluded that the community engagement events and PSAs effectively reached local officials. “We found that adults were more concerned about marine debris — and more willing to support some sort of policy that might address marine debris,” Stevenson says.

In short, hands-on science outdoors and in the classroom, coupled with student outreach, successfully helped to increase the environmental literacy of the community.

THE COLLECTIVE ABILITY TO TRANSFORM

The idea of environmental literacy rippling throughout an entire community kept reappearing in the lab’s research.

Lauren Gibson, a former Knauss fellow with Sea Grant, completed her Ph.D. at NC State this year and now serves as a special advisor for youth engagement at NOAA. Gibson spearheaded work to define community-level environmental literacy, convening 26 researchers from seven different institutions for a discussion at NC State.

Their discussions revealed that a community-level understanding of environmental issues may rely more on connections between people than on every individual understanding the issues in detail. “It’s maybe not important that every single person understands the complexities of the issues,” says Stevenson, who was the lead faculty on Gibson’s project. “But it is important that the community as a whole understands the issues and what the challenges are, and there’s a mechanism to get people’s voices and values at the table for some collective decision-making and collective action.”

Gibson surveyed hundreds of high school students across North Carolina, using that data to find out what drove young people to take environmental action in their communities.

“We found that students were more likely to take large-scale environmental action — like pushing for local policy change or organizing litter cleanups — if they felt connected to and trusted by their community,” Gibson says. “While this trust and connection didn’t matter much in a student’s likelihood of taking small-scale action, like picking up trash on their own, it was super influential in these larger collective actions.”

Stevenson says that these findings suggest that we need to conceptualize behavior change in new ways when thinking about large-scale environmental action. “We need to be thinking about more social-capital kinds of things — talking about issues, the number of people you’re talking to, trust in the community, and a feeling of connectedness that seems to bring about collective action,” she says.

LOOKING AHEAD: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON RESILIENCE

Stevenson’s lab now is building children’s personal resilience directly through a new Sea Grant-funded project in Carteret County — with plans to expand into Durham, Beaufort, and Craven counties.

“Often resilience education focuses on the ecosystems primarily,” says Stevenson. “Our approach is really talking about the ecosystems and the community and the people all as integrated parts to this whole system. You can’t face environmental challenges unless you have the tools to be resilient yourself, because these things are really scary.”

Stevenson is collaborating on the new resilience project with Patrick Jeffs, a positive psychologist and founder of The Resiliency Solution, which creates system-based answers for chronic stress and burnout in the workplace. As a resiliency trainer — with 15 years of experience studying personal resiliency — Jeffs helps people process their stress and problem solve.

“We’ll give teachers practical tools to help kids cope with life in middle school, life in a community that is just coming out of COVID and that will continue to get hit with hurricanes,” Stevenson says. With the potential to build both personal and community literacy and resilience, Stevenson sees environmental education as a vital — but still largely untapped — resource in the fight against climate change. “We’re missing something if we’re not looking at education as a data source for what we should be doing for the future,” she says. “We’ve got all these people learning and investigating that have a vested interest in the future because they’re young. We’re training them to think critically and understand what’s going on and make plans for the future, so we should be listening to them, too.”

MORE

- The Environmental Education Lab

- The Marine Debris Education Project (video)

- Kathryn Stevenson on how kids inspire adults on climate change

- Danielle Lawson on children communicating climate change to parents

- Jenna Hartley on engaging students

- Coastwatch contributing editor Lauren D. Pharr’s “Troubled Waters,” which discusses Jenna Hartley’s projects

- Coastwatch resources for teachers

- The Community Collaborative Research Grant Program also has supported Kathryn Stevenson and the Environmental Education Lab’s research, as well as new work from Liz DeMattia of Duke University Marine Lab.

Hanne Parks, a science communication intern with North Carolina Sea Grant, worked for the Environmental Education Lab as an undergraduate research assistant at NC State University, where she is now pursing her masters in fisheries, wildlife, and conservation biology. She has served as an environmental educator in roles across the state, including internships at the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island, North Carolina Botanical Gardens, and Highlands Biological Station.

- Categories: