Even as our state’s capacity for seafood processing declines, wholesalers and distributors have built a network that rapidly deploys initial aid to coastal communities after hurricanes.

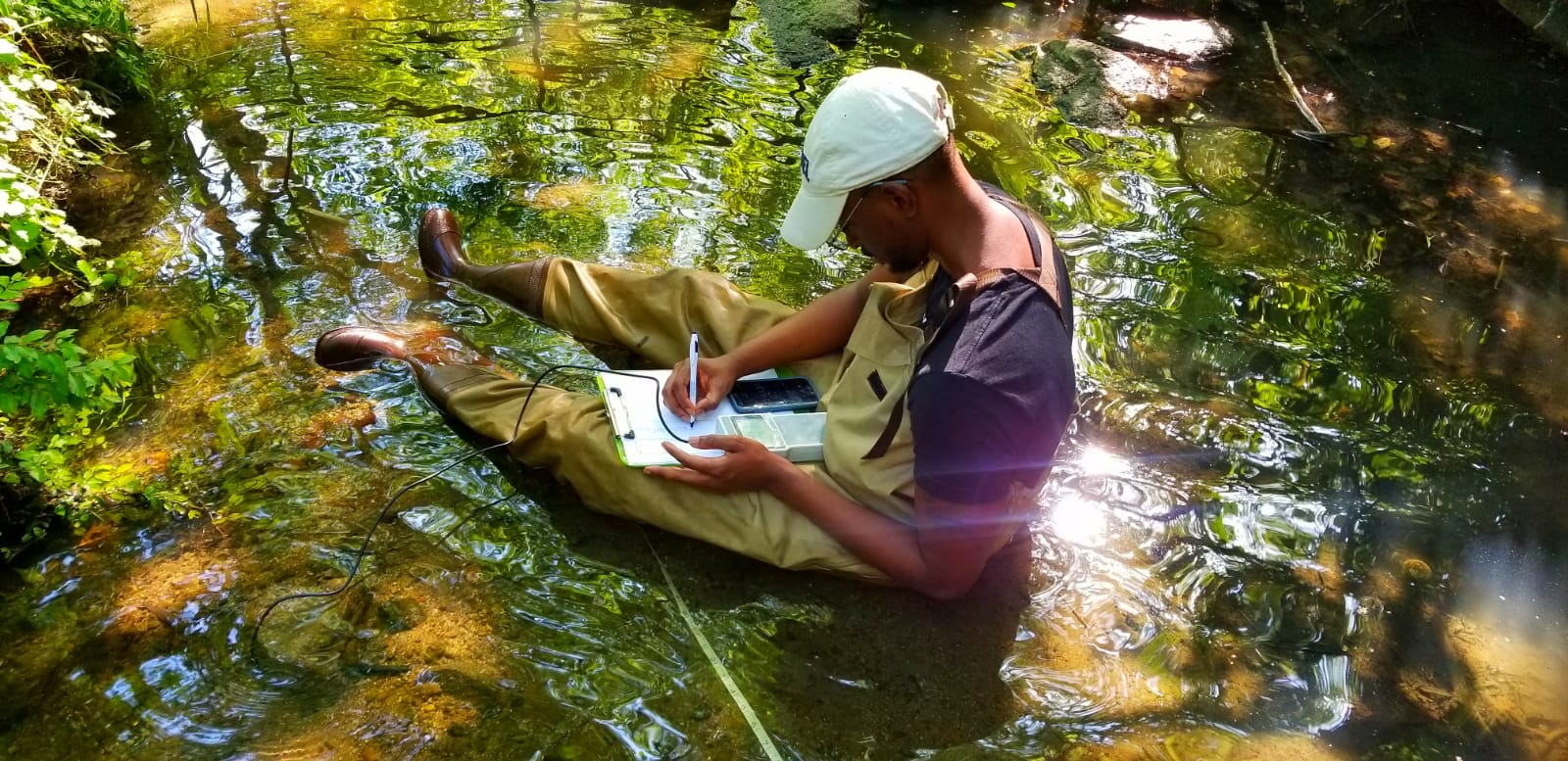

In partnership with the William R. Kenan Jr. Institute for Engineering, Technology, and Science, North Carolina Sea Grant’s Community Collaborative Research Grant Program supported “In the Wake of the Storms: Working Waterfronts and Access in Coastal North Carolina.” Susan West, journalist and project co-director, served with Barbara Garrity-Blake, project director, alongside Scott Baker and Sara Mirabilio, fisheries specialists with North Carolina Sea Grant. Their team conducted interviews in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence.

North Carolina fish houses tend to be small, rural businesses nestled off the beaten path in the nooks and crannies of the state’s meandering shoreline. But even the most remote and isolated are connected by an impressive communications network that kicks in when hurricanes strike the coast. Word-of-mouth news travels fast on the seafood industry pipeline, and seafood wholesalers are often the conduits for getting resources to disaster areas quickly.

A Cedar Island fish house, for instance, served as the staging ground for local fishing boats hauling bottled water, cleaning supplies, and other donated goods from the Down East area of Carteret County to Ocracoke Island where homes and businesses were severely damaged by Hurricane Dorian in 2019. Watermen and other volunteers from Ocracoke and Hatteras — armed with everything from mops to chainsaws — had rushed to Carteret County communities hit hard by Hurricane Florence the previous year.

“If something affects any coastal community, it affects us,” reported a seafood distributor in Chowan County.

Barbara Garrity-Blake, project director for “In the Wake of Storms” and a cultural anthropologist at Duke University Marine Laboratory, says working waterfronts serve as gathering places and information hubs in many communities.

“So, it makes sense that fish houses continue to play a role for the community in storm recovery,” she explains. “They have their pulse on where needs are greatest and have access to boats that can reach hard-hit areas before roads and bridges have been cleared and repaired.

The Decline of Seafood Processing

“In the Wake of Storms” assessed changes in seafood wholesaling capacity in North Carolina, updating fish house inventories completed in 2007 and in 2012. We asked seafood packers and distributors questions about profitability, business model adjustments, domestic product trends, and market challenges and opportunities. We also sought information on how the seafood industry prepares for and recovers from hurricanes.

Our research found that North Carolina continues to lose seafood processing capacity. The state currently has 76 active seafood wholesalers, a 41.5% reduction since 2000.

This trend is consistent with information on commercial fishing from the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries that shows a 40% decrease in the pounds of seafood harvested annually and a 48% drop in the number of active commercial fishing license holders during the same time period.

Wholesalers pointed to the decline in the availability of North Carolina wild-caught seafood as the main challenge facing their businesses and identified over-regulation, fewer fishermen, and degrading water quality as contributing factors.

“Attrition is a problem for the seafood industry,” said a dealer, noting that the number of fishermen selling shrimp, crabs, and fish to his fish house had sharply declined over the last two decades, as fewer young people turn to commercial fishing careers. Almost as dramatic as the immediate market fallout are the long-term consequences for sustaining social networks as young fishermen find a shrinking community of peers at the local fishing docks to help them grow their businesses, learn how to engage in the fisheries management process, or fend off threats to their livelihoods. To help bridge that gap, North Carolina Sea Grant has sponsored leadership retreats where young fishermen network with fisheries managers, scientists, and their peers from other counties.

“Seafood is a highly competitive market, and it is hard to establish consistency,” said a seafood distributor in Pender County. “There is not enough local product, not enough watermen. To get product to our customers, we buy imported seafood if it is not available in North Carolina.”

Despite heightened concern over the loss of market share to seafood from other countries, wholesalers differed on the general health of their businesses. “It’s always been an ebb and flow of good and bad,” said a Dare County dealer.

Fish house owners reporting positive change credited the addition of retail outlets or value-added products to business models.

“The retail market makes the profit and pays the bills,” said a fish house manager in Hyde County.

Some mentioned the influence of consumer education campaigns by NC Catch and other local seafood organizations. “Groups have done a great job branding local products,” said a Pamlico County seafood packer. “Now we have the public wanting fresh local seafood, but we might not always be able to provide that product.”

Even though some businesses had not fully recovered from Hurricane Florence at the time of our interviews, fish house owners did not perceive storms as a nail-in-the-coffin threat.

“I’m not afraid of hurricanes,” a seafood distributor said. “I’m afraid of uninformed politicians.”

In the Aftermath of Hurricane Florence

In September 2018, slow-moving Florence made landfall near Wrightsville Beach and battered North Carolina for days with storm surge flooding and record-breaking rainfall, resulting in statewide losses totaling $22 billion. Damage to fish houses ran the gamut from power outages to the destruction of docks, buildings, and equipment. In some communities, boats sank or were tossed unimaginable distances. Falling trees smashed crab pots, and nets were ripped to shreds by debris floating through yards or buried in a sloppy mix of mud and marsh grass. Floodwaters also swept away fish houses, industrial coolers, and docks.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, working with North Carolina Sea Grant and the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries, found that 65% of seafood dealers in the state reported damage. Estimated losses were $12.9 million to facilities and $20.0 million in revenue.

Businesses in central and southern counties sustained the most infrastructure damage, but disruption of the seafood supply chain affected fish houses everywhere. “We had no physical damage, but we lost income,” a fish buyer on Hatteras Island explained. “There was diminished effort for five days preparing for Florence, and for at least five days afterwards, due to rough seas.”

Most wholesalers, however, experienced much longer disruptions. Nearly a year after Florence, a Pamlico County seafood dealer reported that his business had not fully recovered. Florence had torn apart his fish house, scattering remnants downriver for miles, and fishermen who had sold their catches to him had to find alternative unloading docks and markets.

“They all can’t run back to me, turning their backs on those who took them in,” he said. “So even now, I do not have the fishermen or the product I once had.”

All fish houses had a storm preparation protocol, and some dealers had taken innovative steps to lessen storm damage. Electrical outlets in one Carteret County fish house were installed four feet off the floor, and a Pamlico County fish house was being rebuilt with mobility in mind so that equipment could be rolled to higher ground.

“It’s a roll of the dice,” said an Outer Banks fish buyer. “You prepare for the worst and hope for the best.”

Wholesalers also noted limitations on how much insurance and loans had helped with recovery. “Nobody insures fish house docks,” a distributor said.

At the time of our interviews, no federal or state disaster relief was available for seafood wholesalers with infrastructure damage from Hurricane Florence.

“If you live here, you kind of have to be self-sufficient, and most people will be able to take care of themselves,” explained a Carteret County dealer. “But if there is a major problem, then everybody contributes.”

A Hyde County wholesaler sends out heavy equipment to help clear roads after storms, and fish houses routinely stockpile ice, a coveted item during major power outages, in the days leading up to a hurricane.

“After Florence,” a dealer explained, “we left the door unlocked and told people to come get what ice they needed.”

North Carolina fish houses also assist with recovery efforts in other states. A North Carolina seafood industry nonprofit sent bulk ice and pallets of donated seafood to feed storm victims and relief workers after a hurricane tore through Louisiana in 2020.

The Pamlico County fish dealer who lost his facility to Florence acknowledged that in the first hours after the storm, rebuilding seemed too daunting — until friends and neighbors and even people he did not know showed up to help him salvage bits and pieces of his fish house. Other seafood dealers in the county donated building supplies to kickstart rebuilding of his fish house.

“People just showed up and helped,” he recalled. “The support from this community made the decision for me. I had to rebuild.” When he later heard about damage to the Ocracoke fish house from Hurricane Dorian in 2019, he organized a fundraiser on his docks. “I don’t know them, but I know what they’re going through firsthand. The fundraiser made me feel like I could finally give back.”

New Challenges

We heard similar descriptions of the network of relationships fueled by reciprocity that assist with hurricane recovery. After we had conducted our interviews for “In the Wake of Storms,” the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the United States, erasing a major source of seafood sales, as restaurants curtailed indoor dining or closed altogether. Again, social networks came into play, this time with new open-air retail markets, home-delivery services, and food bank partnerships.

What we saw in the response to the pandemic confirmed that the commercial fishing industry is adaptive, innovative, and quick to assist and feed its communities. How well the industry adapts to future challenges may hinge on its ability to sustain the vibrant social networks that have seen it through hurricanes and other natural disasters.

MORE

- Susan West’s “Charting the Course” on the aging fleet of commercial fishers

- Sara Mirabilio on North Carolina Sea Grant’s “fish camp” leadership retreats

- Julie Leibach on Florence: “A Slow-Motion Emergency”

- Coastwatch on Hurricanes

- Community Collaborative Research Grants

Lead photo: Brunswick County, North Carolina. Photo by Scott Baker.