NATURALIST’S NOTEBOOK: Field Notes from Bear Island

When it comes to learning about the coast, there’s no substitute for experience. So it is that North Carolina State University students embark upon Bear Island at Hammocks Beach State Park for a first-hand view of the environment.

The field study is part of the semester-long Multidisciplinary Studies course, “Coastal and Ocean Frontiers,” otherwise known as MDS 220. The class is taught by North Carolina Sea Grant’s Lundie Spence, a marine education specialist, and Walter Clark, a coastal policy specialist. Experiencing nature is the best way to judge the value of public trust lands, barrier islands or water quality, they say.

Come along and share the students’ discoveries and observations.

I found the nip to be a very important feature that helped tie together the lectures in class. The real world experience showed the impact that nature can have on one of its own islands. I had never really witnessed firsthand the erosion that occurs due to hurricanes, smaller storms and waves on an island that was not inhabited. It was very impressive to see the amount of sand that had been taken away from the shore all around the island and how it was really changing right in front of our eyes.

After marking off the amount of distance that a homebuilder would have to allow from the first line of sable and natural vegetation (according to the construction set-back rules established by the state’s Coastal Area Management Act), I found that I did not think it was far enough away from the shoreline.

I was impressed with the many different species that lived on such a small island, and how they all adapted to the rough life. Plants adapt to environment by aggressive root systems, wind resistance, bending, and resistance to salt spray, drought and heat tolerance.

The high tide and storm tide are quite different from each other. I can tell the storm tide by some of the debris that has washed up and been caught on vegetation. The storm tide looks even worse in some places that seem to wash away and carry on water during large surges.

CARRINGTON EDMUNDS, a senior from Davidson majoring in chemical engineering

It was interesting to note the wide differences between the regions of a barrier island. As we moved across the dunes, I noticed several different types of wildlife. I noticed a large ant lion. These particular animals create a funnel of sand that traps ants. As the ants funnel down the sand, the ant lions trap the ants in their jaws. This was amazing to watch.

As we crossed the dunes, we noticed some higher dunes and rested our stomachs on the dune structure. When the wind blew, I noticed the light sand whip across the top of the bare dune. It was interesting to note that as we moved further inland, the sand seemed to be less dense and had a really nice consistency to it. It was fine and almost white in color.

As we moved away from the range of salt spray and into the maritime forest, I noticed the presence of live oaks, red bay, wax myrtle and a toothache tree. When the leaves of the toothache tree are on your tongue, they give a tingling feeling.

As we walked around the island, I noticed an inlet hazard area. In this area, you could see just how dynamic the inlet could be. This wa5 evident by the undercutting of the trees that once held the bank in. Fallen trees covered an area from the high bank to the water’s edge.

As we walked, the highlight of the trip happened: Walter noticed an octopus in the water. I have never seen one before. It was a beautiful animal that changes colors as it moves. Another reason why this anin1al was so magnificent was its jet propulsion system. Octopi use jet propulsion to propel themselves through the water.

LANDON LASMITH, a senior from Greensboro majoring in computer science

We begin walking over and across sand dunes pointing out all the plants that we see. There is an abundance of trees that died because of sea spray from the last storm. Certain parts of the island look like dead zones because the trees are gray and lifeless.

We get to the high sand dunes, and Lundie talks about fulgurites. Fulgurites are the term used when lightning strikes the sand and heats the sand up to the point where silicon forms in the sand.

As we’re standing on the top of the dune, I see the whole island, and it is a beautiful sight.

We make our way out of the maritime forest and onto what looks like a big rice field. I soon find out this is a salt marsh. Walter told half of us to jump up and down, while the other half stands still. The marsh shakes under our feet. He explains to us that this is caused by peat compacting when jumped upon. This marsh is covered by peat and glasswort. The glasswort is very interesting because it is a type of pickle, and it’s edible.

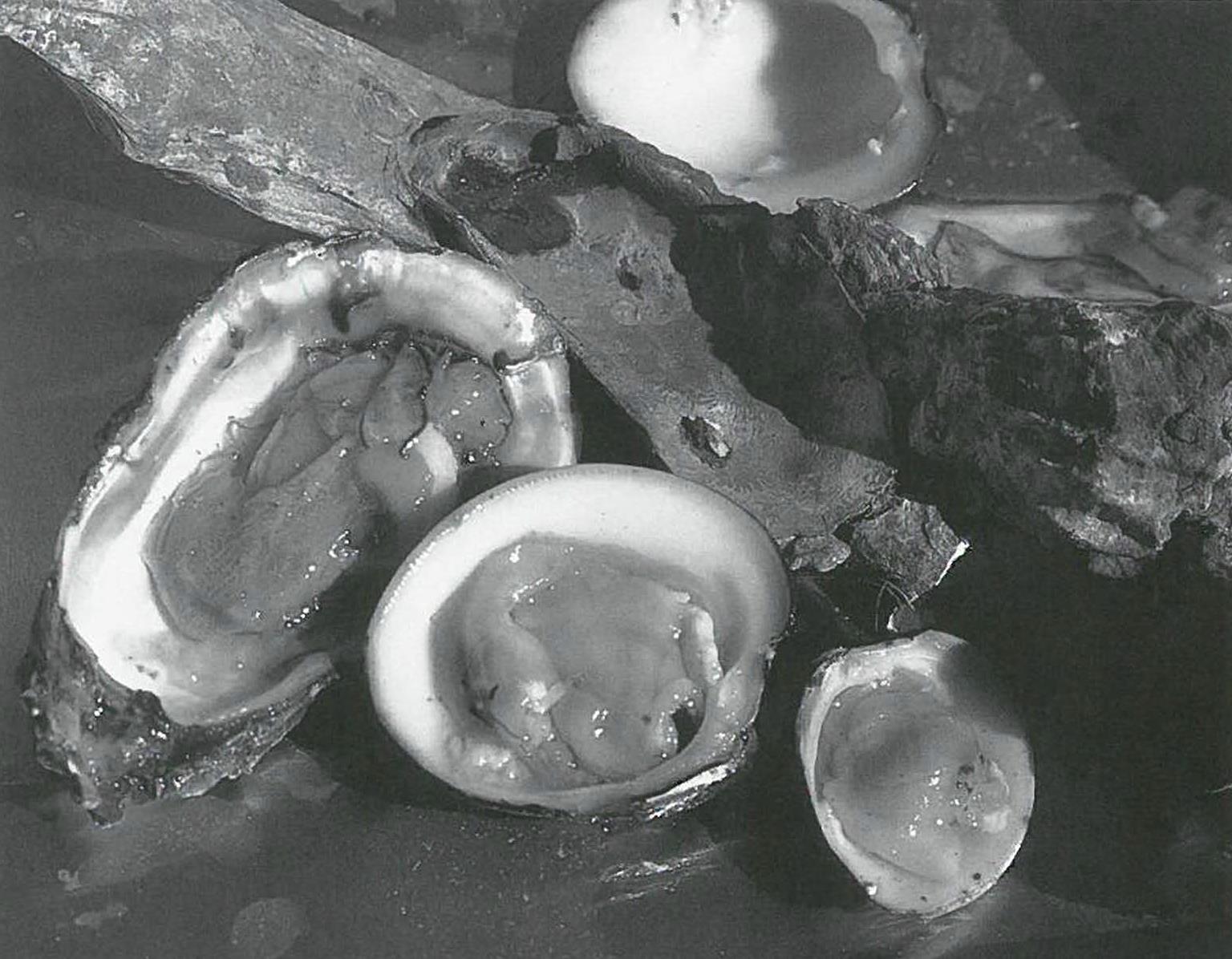

We trek across the salt marsh at low tide, ankle-deep in mud. We make it to the edge of the island and stop on what seems to be an oyster burial ground because the shore is littered with old oyster shells. Lundie tells us the Algonquin Indians would bring oysters they caught here to them break open.

Our group is most determined because we rush to finish all the exercises in the least amount of time. We identify 15 seashells native to the island, study the shore currents’ speed and direction, identify plants seen as natural, stable vegetation, and find out where the setback line would be if we could build a house on Bear Island.

This is the fun part. We finally get to walk through the salt marsh at high tide. There is nothing like the smell of a fresh salt marsh early in the morning. We study the salinity of the water close to land and observe the saltwater and freshwater plants.

AS THEY SEE IT

The Hammocks Beach State Park/Bear Island complex is a perfect classroom — sustainable tourism at its best, say Spence and Clark. Being there, they explain, can mean the difference between simply knowing and really understanding the natural processes and the policies.

In class, a formula on a chalkboard is the best you can do to illustrate building set-back rules prescribed by the North Carolina Coa5tal Area Management Act, Clark says.

”But, it’s a different picture when you actually step off 60 or 90 feet from the first line of stable vegetation — within view of the ocean and signs of change. They can appreciate just how vulnerable man-made structures are.”

Students gain a new perspective on ecology and management issues from the vantage point of a high dune on this undeveloped barrier island. Bear Island has some of the most spectacular, intact dune fields in North Carolina, says Spence.

Students learn that CAMA rules apply only to the edges of developed barrier islands — the ocean hazard zones and the wetland sides. Management rules don’t protect the core of an island — including dune fields and maritime forests that are not designated areas of environmental concern, Clark adds.

But no legislation can protect a maritime forest from nature itself. The Bear Island maritime forest was decimated by Hurricane Fran in 1996. Now students see the beginning stages of its recovery.

Spence and Clark say there is no way to measure the impact of a single field trip.

”But we can be certain of one thing,” Spence offers. ‘They learn that there’s more to the beach than surfing or getting a tan. They will never go to the beach with the same eyes. They understand about wave energy, the sand dunes and the tides.”

This article was published in the Winter 2002 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.

- Categories: