The Mystery Ship Off Pappy Lane

How Science and Sleuthing Uncovered the History of a 58-Year-Old Shipwreck

Weeks of diving and mapping revealed a ship that had found its way from the turbulence of the Pacific Ocean to its final resting place at the bottom of the shallow, murky Pamlico Sound.

On a calm day in Rodanthe, North Carolina, the stern of the “Pappy Lane” shipwreck is visible from the shore. Since it ran aground on the shallow bottom of the Pamlico Sound in the 1960s, not far from the end of the road that is its namesake, it has transformed from ship to kite-surfing obstacle. A red flag marks its place for the rough days when water rises and overtakes it.

As the years, hurricanes, and tourists pass through Hatteras Island, the shipwreck has scattered into fragments. The wind and brackish water stripped its deck away, leaving less than 15 percent of its structure.

It faded from the island’s memory even faster. Hatteras Island boasts a long list of family names that have persisted since European settlers washed onto its beaches. You can find each name engraved into the 72 small cemeteries clustered beside N.C. Highway 12, printed on fish houses, and written on reality advertisements. With generations of family stories to tell, the residents of the six Hatteras Island villages have a deep sense of history. But when it comes to the story of the Pappy Lane wreck, no one remembers much.

“It’s kind of like a car parked on the side of the road,” says Nathan Richards, director of the Program in Maritime Studies at East Carolina University. “When was it parked there? People forget.”

Richards had researched the wreck since 2010, but besides the kite surfers dodging its oyster-encrusted frame and a mark on a laminated paper map in the tower of the nearby historic Chicamacomico lifesaving station, he had found little tangible acknowledgement of the wreck on the island.

But then the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) proposed phase II of a replacement project for the Bonner Bridge. The project would include steel pillars within 100 meters of the wreck. With the ship’s identity unknown, the bridge threatened to damage what could be a site of historical and cultural significance.

To minimize the impact of the bridge’s construction, a complete assessment of the wreck was warranted, according to NCDOT documents. The assessment, headed by Richards, represented a collision of history and future development. This ship, lying disregarded half in the sound, half in the sun, had a story to tell — one that could impact the infrastructure on an island with its only road frequently cut off by ocean overwash.

With the assistance of the NCDOT, the Pappy Lane Shipwreck Project began. Richards and a team of nine East Carolina University’s graduate students rose early nearly every fair-weather day to go to the wreck. Each morning during the 40-minute drive from ECU’s Coastal Studies Institute (CSI) in Wanchese to Rodanthe, they towed their gear and boats across the Bonner Bridge onto Hatteras Island. The bridge’s replacement ran beside them, interrupting their view of the Pamlico Sound as construction cranes and boats did their work.

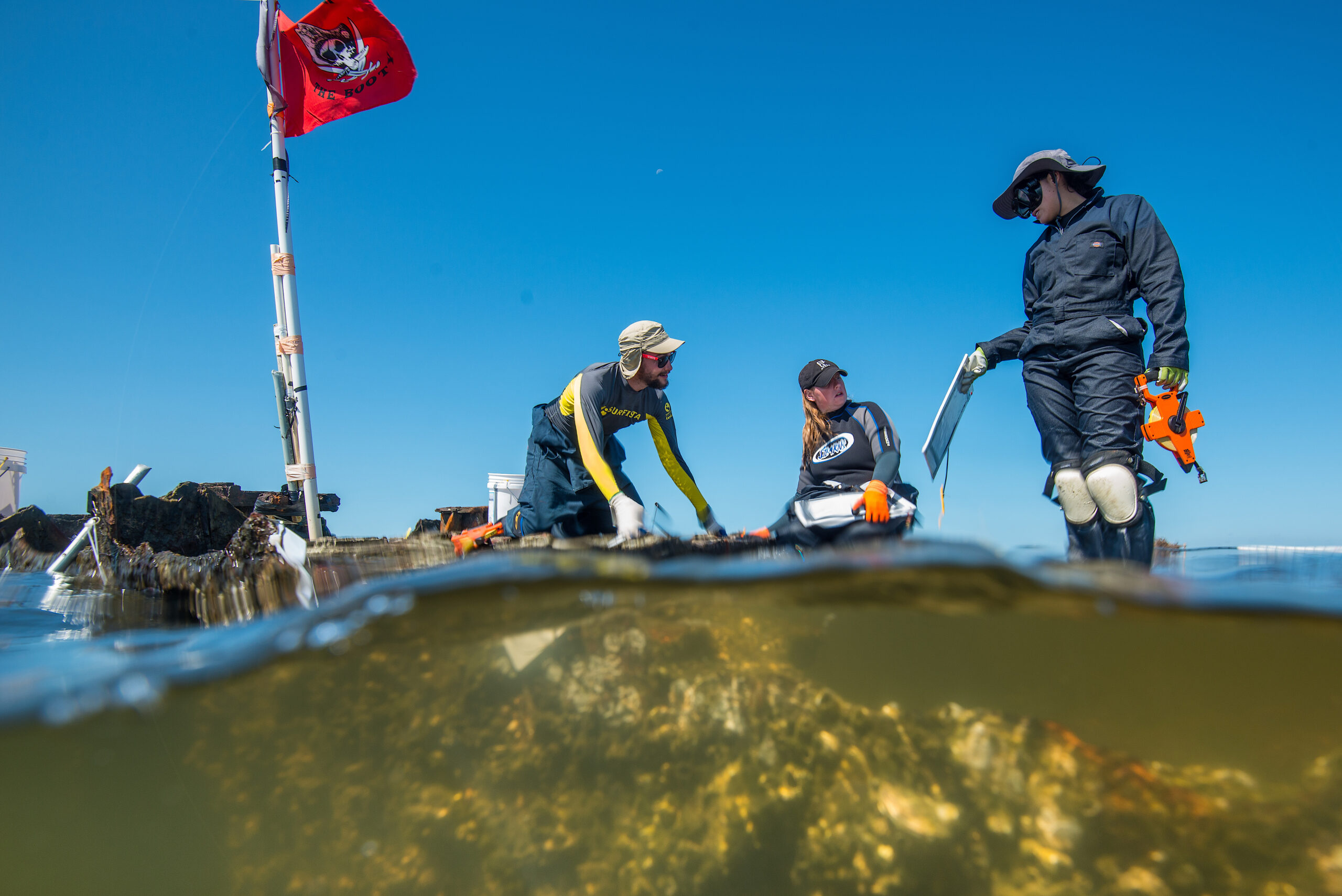

In Rodanthe, they put their boats in and rode to the wreck a hundred yards offshore. Working in chest-high water, some students strapped on scuba gear to dredge the submerged hull, while some stuck with snorkel gear and drew features of the ship onto mylar sheets. Microbiologists sometimes joined them to study the microbial communities making their home on the ship, investigating how they ate away at the vessel.

It was a tricky ship to study. With the vessel half underwater, both archeologists and microbiologists developed multiple methods for research. Even for the outreach portion of the project, John McCord, CSI’s director of outreach and education, came to the site prepared to photograph in the water, on the surface, and in the air. Underwater photography and drone footage not only connected the public with the project but provided high-resolution aerial photographs and data for a 3-D model that aided in Richards’s research.

The lack of oral history about the wreck made uncovering its identity even trickier. While there were a handful of accounts from island residents, they conflicted, some saying it belonged to the National Park Service, some saying it was a gravel barge, some saying it was a Great Lakes steamer. Richards specializes in studying abandoned shipwrecks with little historical record, but the Pappy Lane mystery was surprisingly difficult to crack.

“This one was just particularly infuriating, because it’s a ship that was lost not that long ago,” says Richards. “There are plenty of people still alive that were around when this thing met its end in one way or another, and no one really knew. They just knew and remembered it always just being there.”

Steadily, Richards and his team gathered enough archeological evidence from the wreck to pin an identity to the discarded artifact, finally solving a mystery written in the shallow waves. What the weeks of diving, drawing, and mapping ultimately revealed was a surprise to all — a ship that had found its way from the turbulence of the Pacific Ocean to its final resting place at the bottom of the shallow, murky Pamlico Sound.

The Art and Science of Maritime Archeology

Hatteras Island — a spit of land only a few hundred yards at its thinnest — was not always where it is today. At one point, the island resided 50 miles further out to sea. Since its formation, the wind and waves slowly washed sand over the beach and back into its marshes, pushing it slowly inland and keeping it above the 1 foot per century of sea level rise since the island’s formation over 3,500 years ago.

While the journey of the boat that came to rest off Pappy Lane only took decades, the ship traveled a much longer distance than Hatteras Island’s migration. But with only a disintegrating mass of iron and little historical documentation offering clues, retracing what happened required detective work. An Australian-born and educated maritime archaeologist, Richards came to the Outer Banks an expert in the kind of investigation needed to uncover the story of the Pappy Lane wreck. He specializes in identifying abandoned shipwrecks, which are particularly difficult to study.

“There’s no fanfare associated with their loss,” Richards says. “When ships are discarded, people aren’t pulling their hair out and yelling, ‘catch my baby.’ There’s not hundreds of thousands and millions of dollars at stake. People are throwing away what they think is trash.”

That meant there was no acknowledgement of the Pappy Lane wreck when it occurred, either in local newspapers or government documents. Because the wreck has even faded from the memories of Hatteras Island residents, with so few leads Richards had to get his hands in the Pamlico Sound’s mucky sand and do what he does best.

He led his team of ECU graduate students to create a finely-detailed map of the site, which was compared to blueprints from historical vessels, and also to excavate parts of the shipwreck. They spent a month out on the wreck recording every facet of it, looking for the few tiny, miss-able details that would ultimately pin a history to the ship.

Every workday, Richards and his students jumped into chest-high water with wetsuits, scuba masks, waterproof mylar sheets, pens, and diving slates. They drew the site on the mylar sheets while snorkeling and carefully climbing over the ship. Within three weeks, they had dozens of drawings.

In the end, they stitched together and transposed 177 drawings onto a site map with a scale of 1 foot of the ship to every 1 inch on the map. But the site map alone wasn’t enough to unmask the wreck’s identity, calling for a rare solution — dredging, a method Richards hadn’t used in a decade.

1 of 5000 Shipwrecks

Nathan Henry, assistant state archaeologist and conservator, had monitored thousands of North Carolina’s shipwrecks while working at the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources’ Underwater Archaeology Branch Preservation Lab.

“We track the wrecks that are under the state’s ownership and protect them as best we can,” says Henry. Protecting the wrecks means issuing permits to construction sites, treasure hunters, and research teams to document, as well as to excavate, with as little disturbance to sites as possible.

The preservation lab in Kure Beach, tucked in among the live oaks, has an ocean view, saltwater tanks full of Civil War relics, and tables covered in muskets and cannon balls. With a little chemistry, Henry dried out and preserved wooden and iron artifacts before sending them off to museums and universities. But it’s generally best to leave the state’s shipwrecks and their cargo — which range from Native American dugout canoes to World War II tankers — where they settled.

The 5000 documented wrecks in North Carolina’s waters far outpace the resources to properly preserve them if taken onto dry land. “We haven’t recorded all of them. Never will,” says Henry. “There’s little creeks that just have boats on top of boats on top of boats all in there.”

Even if the majority of these wrecks remain forever submerged, he says, the details we collect and record from them add critical pieces to North Carolina’s identity. “There’s a lot to discover out there every time you find one more shipwreck. I think it’s important to document that as best you can and collect as much information as you can.”

Henry’s Underwater Archaeology Branch issued one of the permits for the Pappy Lane project, mandating dredging of the stern and three cross-sections of the ship. By limiting dredging to targeted areas of the shipwreck, based on historical records and an understanding of ship construction, most of the area would simultaneously remain undisturbed and allow for the potential discovery of new information.

Exposed

The process of dredging requires physical removal of some parts of the wreck, exposing more of it to oxygen and other environmental forces that can lead to corrosion and degradation. Even if researchers rebury newly exposed materials, it can take time for oxygen-starved conditions to reestablish and stop the iron from rusting. Because dredging causes damage, it is only undertaken to answer a specific research question — in this case, about the ship’s identity — and only when meticulous records of activities before and after excavation are made, allowing for later reconstruction.

After researchers properly anchored their boat, which also served as the dredging platform, the team rolled out the hoses, went in with scuba gear, and turned on the pump. They fanned sediment to the dredge head and slowly moved down through layers of sediment and oyster shell, which periodically stuck in the hose, until the hull was exposed.

“There was a moment in the field when we were about to excavate the stern when we realized what the stern was,” says Richards. “This sort of flat-bottom tunnel stern. At that point it became clear that I had a variable that was really important. That’s what led us to the Landing Craft Support, Landing Craft Infantry identification.”

Finally, the team had a lead on the ship’s purpose. It belonged to a class of World War II gunboat.

The Microbiologists — and a Crucial Clue

Shallow, brackish water feeds the salt marshes on the sound side of Hatteras Island. The bands of black needle rush and green cordgrass hold in place dark, compact sediment rich in organic matter, the kind that flip-flops disappear into, the kind that makes the air smell like rotten eggs at low tide. The teams of archeologists and microbiologists working at the Pappy Lane wreck were familiar with that smell. Yet, sometimes, they would smell something different —something that helped unlock the wreck’s identity.

But Erin Field, a microbiologist at East Carolina University, wasn’t there to discover the ship’s identity. She and graduate students Cody Garrison and Kyra Price were drilling out pieces of the ship below the surface to study how microbes interacted with the ship and contributed to its deterioration — a process called biocorrosion.

It was a unique research opportunity. Plenty of light penetrated the shallow water submerging the vessel, so Field knew there would be an abundance of life to study compared to deep-water wrecks. Most unique, though, was a permit to drill off samples of the ship.

“Most of the time with shipwrecks, you don’t necessarily want to take pieces of the historical wreck away,” says Field. “So it was a really great opportunity to take samples and use them at the lab.”

At the lab, they scraped off the surface of the metal, where the microbes lived. Past studies have suggested that iron-oxidizing microbes can colonize and encourage biocorrosion.

“We know they’re in sediments, we know that they’re in the water, but we’ve never shown that they’re on shipwrecks,” says Field.

She and her team found them on all of their samples from the ship.

“It was really exciting because it was the first time that had been shown on a shipwreck,” she says. “If we can know who the microbial community members are, where they tend to be, and understand how fast they can degrade, maybe we can use that information to develop preservation methods to protect our shipwrecks.”

Field’s team also discovered something else. As they drilled out samples from the ship below the surface, they smelled oil. Once they took those pieces back to the lab to study the vessel’s microbial communities, in fact, they found oil contaminating their samples.

This small piece of evidence helped point Richards to a vessel in the historical record: a World War II gunboat turned fuel barge. The field work, historical research, and smell had all lined up. Two names, the LCS(L) 123 and the Hunt Bro. No. 10, finally found their way to the ship off Pappy Lane.

From the Pacific to the Pamlico

In the spring of 1945, Marty Heffren, a crewman in the U.S. Navy, and the boat, USS LCS(L)(3) 123 traveled together. Starting in San Diego, Heffren neatly recorded their progress on the Pacific Ocean in a diary, calculating the numbers as they moved toward the war.

April 18, 1945 Underway as before. Traveled 1,147 miles, 1357 to go.

April 23, 1945 Underway as before. Traveled 2,210 miles, 300 left to go.

April 30, 1945 Underway as before. Set clocks back half hour making 15 hours ahead of East Coast.

On May 10th, they sighted Okinawa. Heffren continued to punctuate the horrors of battle in his diary as steadily as he logged the miles left until he reached it.

May 12, 1945 Ran into a storm and then in the worst of the storm we discovered a light shining off our starboard bow in a distance. It was a skunk (suicide boat) and it almost lured us to a reef. We only missed the reef by 10 furlough or so and if we would have hit there would have been no survivors in the rough sea.

May 15, 1945 Went on night patrol duty off . . . southern tip of Okinawa. It’s named Hellhole because of air raids suicide boats coming in every night. I hope it doesn’t live up to its name . . .

May 27, 1945 At 0730 three . . . suicide planes attacked our patrol with very disastrous results both tom them and to us . . . All of our guns opened fire and after being hit the plane tried to dive on the DD 515 Anthony but it just missed the bow. As it passed over the bow, the pilot dropped on the deck of the destroyer, dead. . . We were the first ship in our group to shoot down a plane.

As part of a Landing Craft Support flotilla that specifically launched to fight at Okinawa, Heffren and the LCS-123 helped battle kamikaze planes, put out fires on larger ships, provided damage control parties, and pulled hundreds of men off damaged ships and from the water. Because of their widespread activity in their relatively short career, these small, flat-bottomed LCSs earned the nickname “Mighty Midgets.”

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the LCSs were dispersed throughout the world. Beginning in 1946, 51 of the remaining vessels were stricken from the Navy Register and sold for scrap metal or to commercial fishing companies. In an attempt to bolster allied militaries decimated in the war, many were transferred to foreign fleets in France, Vietnam, and Japan. They served less than two years for the United States during World War II, but some spent over two decades in the South Vietnamese Navy, serving as its first real warships.

The LCS-123 was one of the first of its class sold to a private owner: James L. Teagle of Hampton, Virginia, in 1947. In Virginia, the ship became the Hunt Bros. No. 10, operating under W. P. Hunt Company, which bought it from Teagle. A Hunt family friend, skilled mechanic, and jack of all trades, Teagle oversaw the conversion of the warship into a tank barge, pulling off the deck and putting in new bulkheads in the late 1940s.

William Powhatan Hunt II, who talked with Richards, was about seven years old at the time his father purchased and began converting the vessel. Hunt recalled a discovery as workmen cut open the bulkhead: a room, welded shut, full of weapons.

“Someone made a big error,” Hunt said. “They had to call every part of the military. The military came out to seize the weapons that they didn’t even want in the first place.”

Richards compared the historical account from W.P. Hunt II with archeological evidence and says the “best guess — and a good one, I think” — is that the wreck and the Hunt Bros. No. 10 are one and the same. “But it isn’t definitive at the moment,” he adds. “I’m still on the trail of this.”

The vessel operated during the decline of the maritime transportation industry and the rise of roads and oil pipelines. Hunt’s company underwent multiple evolutions in its last decade to stay afloat, finally becoming a seafood company.

In the midst of those changes, the Hunt Bros. No. 10 faded into obscurity. Its last definitive entry in the historical record, from 1965, reads “out of documentation.” The ship might have had one final life in service to Roanoke Island’s Daniels family, who might have it used to salvage barges.

Without documentation, though, Richards is hesitant to say this was how the ship off Pappy Lane spent its final days — which remains a mystery.

- NC’s first Heritage Dive Site, featuring a Civil War blockade-runner

- “Assessing Shipwrecks: The Value of Preservation”

- the science of shipwrecks

- a shipwreck at Edenton

- Coastwatch on coastal history

India Mackinson is pursuing a masters in environmental management at the Duke University Nicholas School of the Environment. As a lifelong resident of the Carolinas, she studies climate change’s impact on coastal communities in the Southeast.

- Categories: