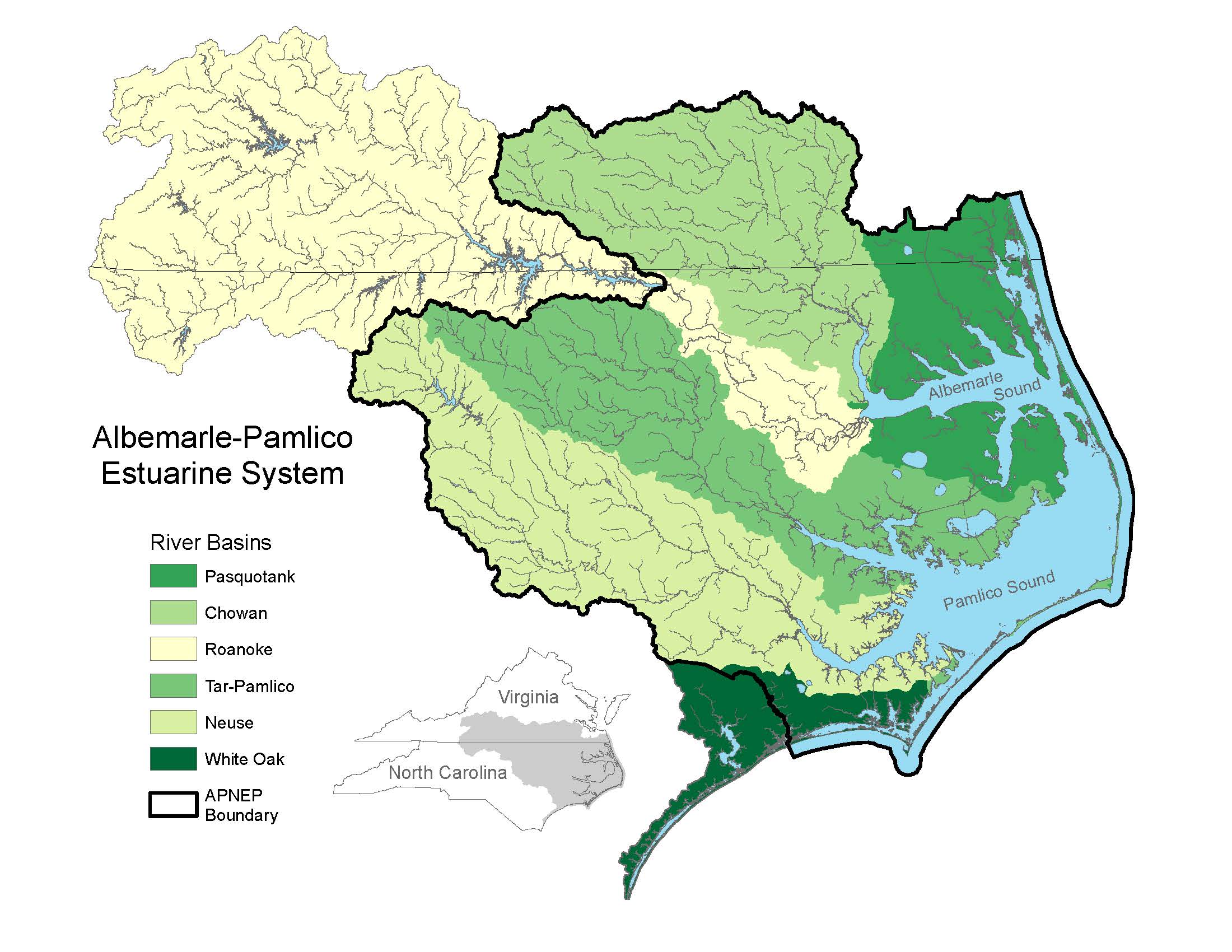

Estuaries are transition zones where land meets water, ocean meets rivers, and saltwater meets fresh. They are also “the nurseries of the sea,” supporting juvenile fishes, crabs, and shrimps as they transition into adulthood by providing marshes, seagrasses, and oyster reefs — habitats that allow these species to find food and remain safe from predators when young.

In fact, these habitats shelter many species vital to local ecosystems, recreational enjoyment, and commerce. According to information from the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership (APNEP), estuarine waters are a habitat for 75% of America’s commercial fish catch and 80 to 90% of its recreational catch.

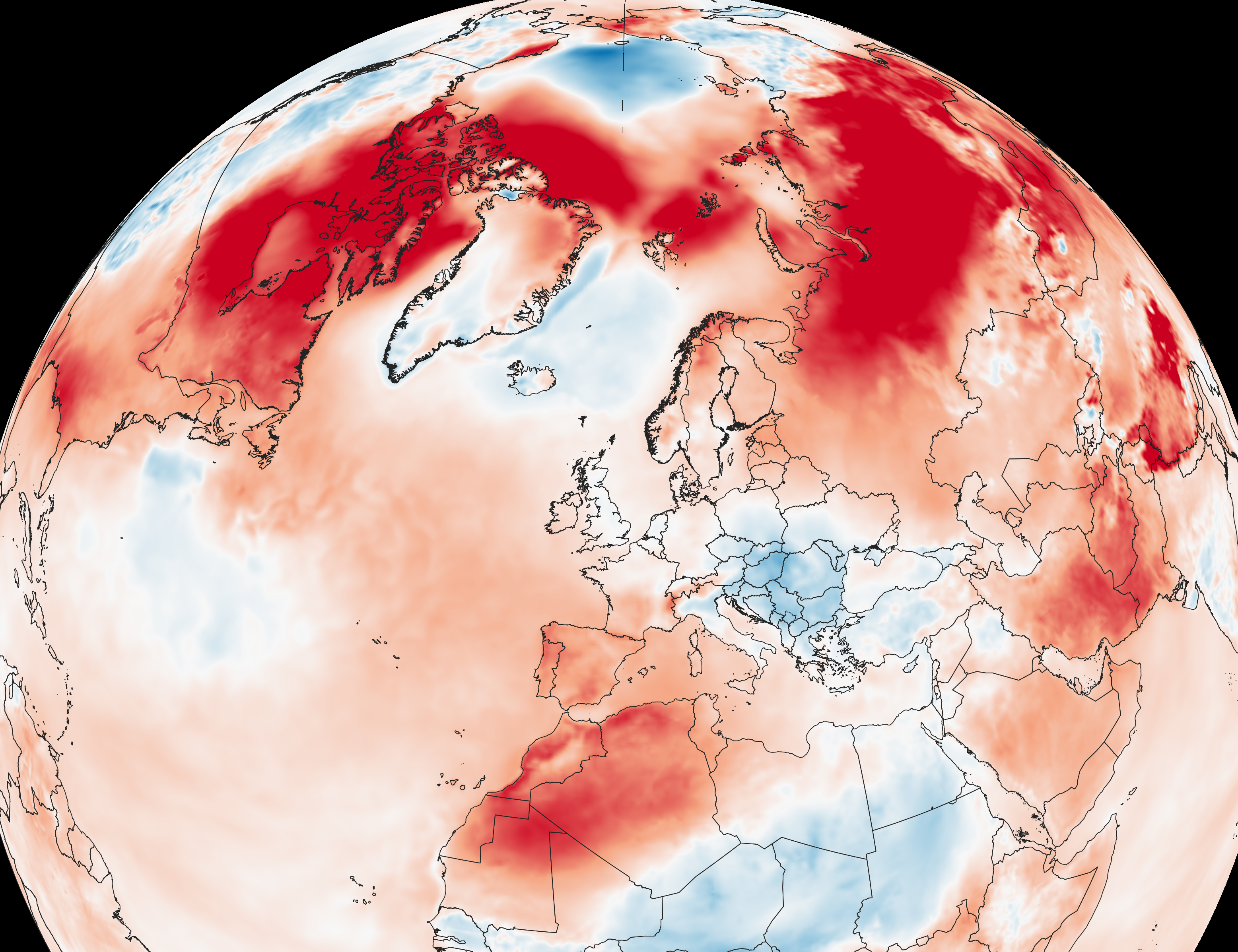

Climate change and shifting water temperatures are among the most pressing considerations for ecosystem resiliency, and estuaries are no exception. Because of this, the lack of analysis of long-term data for North Carolina’s estuarine temperatures surprised researchers who are spearheading a seminal Sea Grant project.

“There’s just this gigantic hole, which is concerning,” says Joel Fodrie, an estuarine ecologist from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS). “Because temperature is a fundamental property of these systems.”

Janet Nye, a quantitative fisheries ecologist at IMS, had previously researched estuarine temperatures in New York. “When I arrived here,” she says, “I asked, ‘What’s the temperature pattern across North Carolina’s diverse estuarine systems?’ And people were like, ‘We’re not really sure.’”

Although various institutions and state monitoring programs have collected these data, no one has compiled them to determine historical trends. Attempting to manage coastal resources and efforts for conservation without knowing these trends is “like trying to fly a plane blind,” says Fodrie.

Fodrie and Nye’s research will illuminate how multiple factors influence water temperatures — and the implications are complex. Temperatures that are detrimental to some species could welcome others, and as species dynamics shift, long-term effects are uncertain.

Predicting temperature changes is a challenge. It may seem intuitive that estuaries would heat up faster, given their smaller volumes in comparison with open ocean waters, but this isn’t always the case.

“Estuaries are relatively shallow,” says Camryn Blawas, a graduate student in the Department of Earth, Marine, and Environmental Sciences at UNC-CH. “But they have a lot of interaction with the atmosphere and the air, as well as oceanic and riverine influence.”

Additionally, increased dredging, new inlet formation from hurricanes, and rising seas can drive water temperature change.

“All of those things are increasing how much ocean water makes it into the estuary every tidal cycle,” says Fodrie.

Furthermore, different locations might not experience these factors equally, meaning that temperature change may vary.

Degrees of Difference

“We’re seeing this signal of increasing temperature in certain places up and down the coast,” says Blawas. “We’re not seeing uniform warming, but on average, we’re seeing a small amount of temperature increase per year.”

These small increases, generally 2º F to 4º F over a 20-year period, significantly affect the ecosystem. “That’s actually a night-and-day difference for some processes and critters,” says Fodrie. “A one-degree change on average, or during a key part of the year — that’s not trivial.”

In addition, the water originating from the Labrador Current and the southern Gulf Stream meet off the coast of North Carolina, further complicating the potential effects of new temperature patterns.

“We have warm water that arises from the south, and cooler water that comes from the north. So we’re in a transition zone,” Fodrie explains. “A lot of the critters that we see, to some extent, are near their temperature range limits.”

Fisheries are particularly vulnerable to these limits. “In cold-blooded organisms, the temperature of their bodies is the same as the temperature of the water around them,” says Nye. “They’re strongly impacted, perhaps more so than a mammal like you and me that can kind of control our body temperature.”

This inability to moderate body temperature means that fishes will follow the waters, moving along with the temperature changes.

Teasing out Temperature

Figuring out how shifting water temperatures drive change is deeply complex.

“Is it the range of temperature? Is it how variable temperature is? Is it the fall temperature? Is it the winter temperature?” asks Fodrie. “It’s difficult to nail down, but it may not be the summertime temperatures, when the water’s hottest.”

Higher temperatures might be ideal or harmful, depending on the species and season. Warmer winters may mean that some species — those historically found farther south — stay longer on North Carolina’s coast, and some might be more tolerant of a certain number of days outside their temperature threshold than others.

That’s why the team collected data on temperature changes throughout the year. Studying winter temperatures to understand warming waters might seem counterintuitive, but these temperatures influence the migration of species.

Although rising summer temperatures might not significantly affect fishes accustomed to warmer waters, increasing winter temperatures could prevent some wintering species from visiting while also inviting some species northward up the coast.

“Winter temperatures are really the thing that has prevented organisms from moving northward before,” says Nye. “But now winter isn’t coming — or at least it’s not as cold.”

Species on the Move

Stone crabs, croaker, white shrimp, and bonnethead sharks have been migrating farther north, following the warmer waters.

Others, such as spinner and dusky sharks, now pass the coast at different times. Instead of May and August, they travel past in April and September. “There’s this widening of that period when they’re passing by,” says Fodrie. “The temperatures are really what they’re following.”

This means that warming waters may lead to the introduction of new species, an abundance of existing species, or fishes remaining in our waters longer. For example, fish such as the spotted sea trout, which are susceptible to colder temperatures, could experience fewer instances of “winterkill” — mass die-offs due to winter conditions.

Although new species in North Carolina waters could even prove beneficial for the state’s fishing economy, it is unclear how this would affect the food web long-term.

In particular, warmer winter waters could lead to the loss of some species that are more tolerant of cooler waters, like summer flounder, smooth dogfish, striped bass, and Atlantic croaker. While anglers previously have found these species in North Carolina during the cooler months, these fishes have shifted farther north as temperatures have increased. In the future, North Carolina fishers will need to travel longer distances to catch these fish — or shift to other species.

Furthermore, increasing temperatures could mean losing crucial vegetation for some of our fisheries.

In Hot Water — Sweltering Seagrasses

“We are a very seagrass-rich state,” says Fodrie. “We have more seagrass than all the other East Coast states combined, except Florida.”

Seagrasses support water quality, providing shelter for fish, helping minimize erosion, controlling the transportation of sediment, and mitigating the effects of climate change by capturing carbon. But temperature change threatens these benefits, because it can negatively impact salinity, sea-level rise, and oxygen levels in the water — which is problematic for the seagrasses and the species they support, such as red drum, blue crabs, oysters, flounder, shrimp, and grouper.

“Seagrasses can’t move,” says Nye, “but the fish are definitely moving.”

North Carolina represents the northern limit for shoal grass and the southern limit for eelgrass, the latter of which is more sensitive to warmer temperatures. Eelgrass has upper-temperature limits of 77º F, and shoal grass 86º F. Although shoal grass might be more resilient, there are concerns that North Carolina will lose most eelgrass by 2050 due to temperature increases.

The Economic Impacts of Changes in Water Temperature

Changes in estuary temperatures and the implications of those changes could be slow and take decades. These subtle changes can be particularly pernicious, threatening ecosystems that provide recreational and commercial benefits.

But warming waters could also have potential economic advantages, at least in the short term. Some species, like stone crabs, croaker, and white shrimp, have become more plentiful off North Carolina’s coast.

A few decades ago, the northern limit for stone crabs was Morehead City, but now their range extends to Hatteras. “Every year they creep perhaps another mile farther north,” explains Fodrie, “and the center of the croaker fishery has gone from near the southern border of the state to near the northern.”

White shrimp can now inhabit the Chesapeake and are more abundant for a longer portion of the year in North Carolina waters than in decades past. This means more shrimp for our state’s commercial fishers, but the economic advantages could prove short-lived. Increases in the numbers of these species could affect the viability of other species we depend on.

Fodrie and Nye’s team hopes that collecting temperature data and assessing temperature patterns will bring answers to such questions.

Charting New Waters

The researchers will share their findings at the conclusion of their project, citing interest from the organizations that have shared data, such as the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries, UNC Shark Survey, National Estuarine Research Reserves, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

They also plan to release an interactive visualization tool on the North Carolina Sea Grant website, where visitors can track changes through the decades.

“There was a lot of interest as I was asking for permission to use certain data sets,” Blawas recalls. “People were saying, ‘Please let me know what you find out, because we’ve had these data for so long,’ and they want to know what trends we see in the temperature.”

Nye says their project is an effort to preserve what people love.

“This project was really to wrangle the data, see what’s happening with temperature, and see if we can give people a sense for how it may affect the species and organisms they care about. People love red drum and seagrasses. They feel a connection with that part of the marine environment.”

MORE

Coastwatch on climate change, the blue economy, fishing, sharks, and other species.

Marlo Chapman is a science communication intern with North Carolina Sea Grant and a graduate student at NC State University studying rhetoric and composition.