North Carolina Cultured Shellfish

As locally grown shellfish like oysters and clams gain attention and market share in the state, North Carolina Sea Grant extension specialists and communicators developed this overview of the industry. Discussions with growers and market research helped identify the attributes of cultured shellfish that both growers and shellfish consumers highly value.

A Timeless Culinary Delight

People have enjoyed eating shellfish for centuries, and possibly even millennia. Historical records point to the establishment of oyster beds as far back as 100 B.C. Ancient Chinese and Roman cultures developed methods for growing and harvesting oysters. In the United States the Eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, played an important role in the Native American diet, and served as a food staple for European settlers. By the mid-19th century, Americans had become enamored with oysters, shipping them inland on so-called “oyster expresses” and “oyster caravans.” Almost every large city in the eastern United States had an “oyster parlor,” a precursor to modern-day oyster bars.

Today, the Southern tradition of oyster roasts — large gatherings where people enjoy oysters cooked over an open fire — is still popular. There also is a growing demand in restaurants for oysters served raw on the half shell.

The hard clam, or quahog, has long been another seafood favorite. Native Americans made beads from quahog shells to use as money — a fact that inspired its scientific name, Mercenaria mercenaria, which comes from the Latin word for “wages.”

While clams are typically served steamed, a market is growing for clams served raw, as well as for use in packaged meals, such as frozen chowders and refrigerated spreads.

Growing Shellfish

Wild shellfish such as oysters and clams have been harvested from North Carolina coastal waters for hundreds of years. But shellfish also can be cultivated. Since 1858, North Carolina has allowed the use of public waters to commercially grow shellfish, provided that producers apply for and obtain a lease.

The N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries oversees the state’s Shellfish Lease Program. The leasing process ensures that shellfish are sustainably grown in high-quality coastal waters, without affecting public access or recreational activities.

To start cultivating shellfish, North Carolina growers usually purchase small young clams or oysters, called seed, from commercial hatcheries or nurseries to stock their leases.

Clams

Typically, clam seed are planted on the bottom of the lease in prepared plots. The seed are protected from predators such as crabs and rays by a mesh covering. They burrow into the lease bottom and extend appendages called siphons, which they use to filter food consisting of a diverse array of microscopic marine plants, or phytoplankton. Clam seed need about two years to reach a diameter of two inches before they can be harvested for commercial sale.

Oysters

To cultivate oysters, in North Carolina growers traditionally planted oyster shells on lease bottoms, creating a place for free-swimming oyster larvae to attach and become oyster “spat.” Growers also planted oyster shells to which oyster larvae have already attached, known as “spat on shell.” After planting, the spat feed on phytoplankton as they grow.

With this production method, oysters are normally harvested once they reach a market size of approximately three inches, which takes two to three years. Because each planted oyster shell typically contains several seed oysters, the oysters grow in clumps that are mainly suitable for oyster roasts or shucking.

In recent years, an increasing number of North Carolina oyster producers have been growing their oysters in the water column. This method entails placing oyster seed into cages that are floated or are suspended off the water bottom. As the oysters grow, they are periodically sorted according to size and are transferred to other cages to reduce crowding.

Growers using this process must also regularly repair, inspect, and clean cages and bags to remove predators such as crabs and to ensure that water flows freely through the oysters so they can feed and grow.

While water-column cultivation is more labor intensive, the technique produces consistently sized, single oysters with deep cups that typically have more meat in them than wild oysters or those planted on the bottom. Because the oysters are not in contact with the water bottom, they are generally free of grit. These attributes are prized by high-end restaurants that serve oysters on the half shell.

Cultivated Shellfish Are A Sustainable, Environmentally Friendly Seafood Choice

Shellfish cultivation is a highly sustainable way of producing seafood. Cultivated shellfish get nutrition from their surroundings, so they don’t require added food, chemicals, or antibiotics to grow. They also can’t be over-harvested, and they relieve pressures on wild shellfish populations. When growers harvest cultivated oysters or clams, they remove no more shellfish from the water than they originally put into it.

The coastal environment also benefits from shellfish production. When oysters and clams feed, they filter water, thereby improving its clarity and quality. In fact, a single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. Clearer water fosters the growth of marine vegetation, which in turn provides habitat for sea life, such as juvenile crabs and finfish.

Cultivated Shellfish Come From Quality Waters

Many North Carolina shellfish are grown in low-populated, rural areas where there is little manmade infrastructure.

Even so, the state vigorously manages its shellfish growing waters to ensure that clams and oysters are safe to harvest. The N.C. Shellfish Sanitation Program regularly collects water samples in shellfish growing areas to test for signs of potential disease-causing microorganisms that could make shellfish unfit to eat. When necessary, it will enact temporary closures of growing areas to protect public health. This may include after heavy rains.

It’s important to note that clams and oysters also can contain naturally occurring bacteria that can make people ill, particularly individuals with weakened immune systems from chronic health problems. Those with chronic health issues should avoid eating raw or undercooked shellfish.

Tracing Shellfish

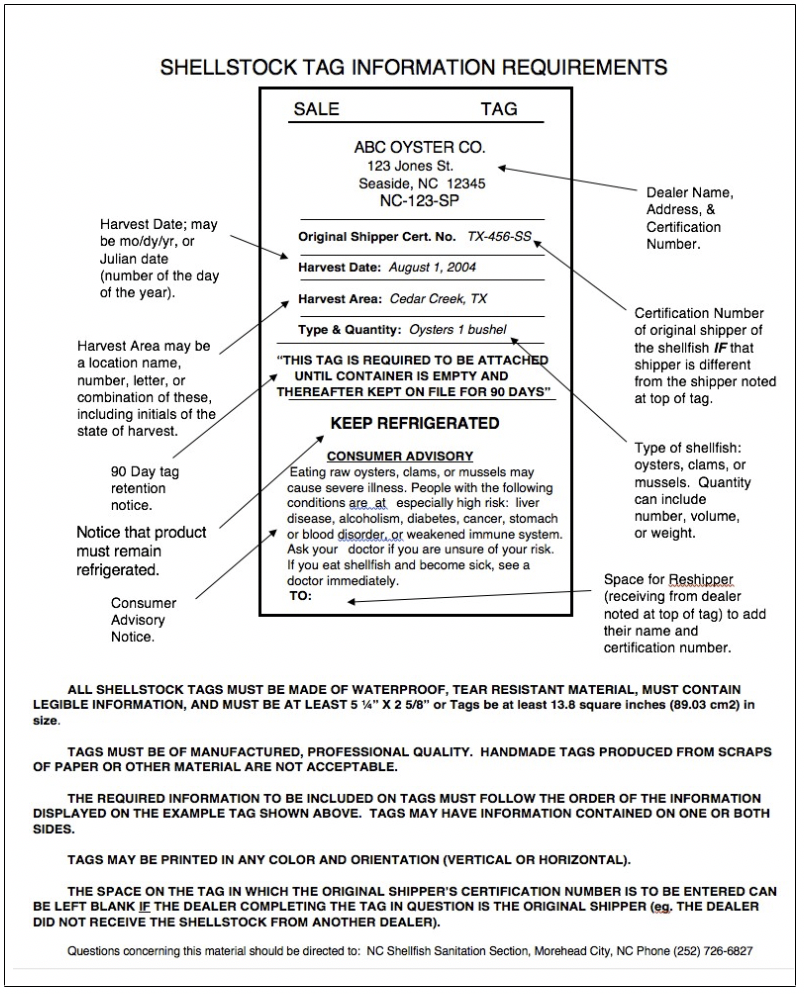

Shellfish growers must record on waterproof, tear-resistant tags the date, the growing area and the quantity of shellfish harvested, along with their individual grower identification information. These tags follow the shellfish stock as it is distributed from harvesters to consumers.

Should someone become ill from eating shellfish, the tags will enable public health specialists to trace clams or oysters from the consumer back through every middleman who handled the product, and finally to the growing area and the grower who harvested the shellfish. Tagging shellfish not only protects public health, but it authenticates where clams and oysters are cultivated.

Buying Local Supports North Carolina Growers

Buying North Carolina clams and oysters boosts local economies and supports the livelihoods of shellfish growers. In 2017, the commercial value of cultivated North Carolina oysters was nearly $2 million, while cultivated clams were valued at about $200,000.

Growing shellfish can serve as an alternative trade for fishing families — one that preserves coastal communities by drawing upon the knowledge and skills of local residents.

Shellfish Offer Health Benefits

Clams and oysters have long been part of the American diet, and these tasty treats fit easily into a well-balanced meal plan. A three-ounce serving of oysters contains 10 grams of protein and only four grams of mostly unsaturated fat. Oysters are also an excellent source of calcium, iron and zinc.

Three ounces of clams contain 17 grams of protein and 1.5 grams of unsaturated fat. They are also a good source of vitamin A, calcium and iron.

Buying And Handling Shellfish At Home

When purchasing clams and oysters in the shell, make sure they’re alive. Their shells should be moist and closed, or should close tightly when tapped, and they should be free of bad odors.

Keep live shellfish at a temperature no higher than 45°F. In fact, 36°F to 38°F is ideal. Discard any shellfish that open during storage or that develop strong sour or fishy odors, or an odor reminiscent of ammonia.

Before shucking shellfish, rinse them thoroughly with cold, running water. A garden hose with plenty of pressure works wonders. Remember to wear heavy gloves when handling oyster shells — their edges are quite sharp.

If you’re buying shucked oysters, look for batches that are plump with a natural creamy color. They should contain no more than 10 percent liquid, and that liquid should be clear or slightly opaque, with a mild odor.

Perhaps you’ve heard that adage about eating oysters only in months with an “r” in the name. That rule doesn’t hold true for cultivated oysters. Today, seafood safety rules require that cultivated live and shucked oysters be refrigerated immediately after they are harvested. In addition, most growers raise sterile oysters, which don’t reproduce and have excellent meat quality year-round. In contrast, wild oysters decline in quality during the summer months when they reproduce.

When shopping for clams, it’s important to know what kind you need. Markets classify hard clams by their size. Littleneck clams are the smallest, at under two inches in length. Cherrystones measure two to three inches, and topnecks are three to three-and-a-half inches in size. Any clam larger than that is a chowder clam.

Bringing Out Flavors

Perhaps you’ve heard of terroir – the combination of soil, climate and other environmental factors that give wine grapes their distinctive character. Similarly, clams and oysters have merroir representative of the waters they grow in. North Carolina growers produce exceptional clams and oysters with unique regional flavors that stem from subtle differences in local conditions at each growing site. For example, some growers raise their shellfish near inlets and saltier ocean waters, while others are closer to fresh water.

According to author Rowan Jacobson, author of A Geography of Oysters and The Essential Oyster, “something about oysters resists every effort to describe them.” Like wine, oysters can have complex flavor profiles. They might first taste salty, then sweet, and end with a floral or fruity finish.

Regardless of where they’re grown, North Carolina oysters are excellent for eating steamed, broiled, char-grilled, fried, baked, in stews or on the half-shell.

Where clams are concerned, littlenecks and small cherrystones are firm but tender, with a mild flavor. Enjoy them steamed, broiled, baked or grilled. Topnecks and chowder clams are less tender, so it’s best to chop them for soups, fritters and stuffed clams. Be mindful of cooking times. Clams should be tender, not tough. And avoid adding too much salt. Clams typically have their own briney taste.

If you enjoy steamed clams and oysters, you may wish to buy a shellfish steamer, which is a large, two-section pot, much like a double boiler. Inexpensive enamel versions are available at general merchandise and most hardware stores.

Additional Resources and Contact Information

North Carolina Sea Grant has produced an educational shellfish brochure highlighting the information above. For hard copies, please contact Rebecca Jones, North Carolina Sea Grant Communications Director, at rejone25@ncsu.edu or 919-515-9069.