By ANN GREEN with Photos By SCOTT D. TAYLOR

Menhaden boats are unloaded at Beaufort Fisheries, where the catch is processed long into the night.

Inside Beaufort Fisheries, the strong smell of menhaden drifts through a dark, empty room. Large cobwebs hang down like a white veil on a light bulb. Huge presses sit empty throughout the room.

“At night, it is like a horror show in here when the plant isn’t operating,” says Jule Wheatly, president of Beaufort Fisheries, Inc.

The plant, which only operates when the day’s catch comes in, is reminiscent of a bygone era when menhaden plants were thriving in North Carolina.

”There used to be seven menhaden plants in Carteret County,” says Wheatly. “Now my plant is the only one left in the state.”

Beaufort Fisheries also is one of only two menhaden plants on the Atlantic Coast. The other plant is in Reedville, Va. North Carolina and Virginia are the only states that have reported menhaden landings along the Atlantic since 1993, according to an Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission draft management report. Before that, there were some landings in New England.

With the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission scheduled to vote on an Atlantic menhaden fishery management plan in January, the Beaufort plant may be closing. The draft amendment — which was developed to address declines in the population of Atlantic menhaden — proposes restricting menhaden purse seine fishing one mile from shore.

“We may not be here after this year,” Wheatly says as 2000 draws to a close. “If the Atlantic Fisheries Commission puts a one-mile limit for fishing we’ll have to close. Seventy-five percent of our catch is from the shoreline to one mile.”

Some citizens in Brunswick County support the restriction of menhaden fishing on beachfronts. In l999, a large fish kill of menhaden was reported in Brunswick County.

“You can’t look at just what is best for menhaden fisheries alone,” says Oak Island Mayor Joan Altman. “You also have to look at what is best for beachfront communities. Many people in our community think that menhaden fishing should be kept a mile offshore.”

For the past several years, Wheatly has been fighting to keep his business open. On a recent day, he holds up a 1998 aerial photo of schools of menhaden near the shore of Core Banks. White spots show dead menhaden; dark spots show live menhaden. All told, there are about 200 million menhaden.

Wheatly says the photo has saved him at many meetings.

“The fish get close to shore, and when the tide goes out, the fish are trapped and often for lack of oxygen die in the center of the school,” says Wheatly.

While sitting in his wood-paneled office, Wheatly also points to other photos, including an old black-and-white photo of a menhaden boat.

“When I was a kid, they had 100 menhaden boats like that one” docked on Front Street in Beaufort, says Wheatly. “Now there are none.”

The only two menhaden boats left in Beaufort are owned by Beaufort Fisheries. On a recent day, the Gregory Poole — a refurbished World War II mine sweeper — is docked at Taylor’s Creek. A small purse-seine boat used to catch menhaden is parked near the stern.

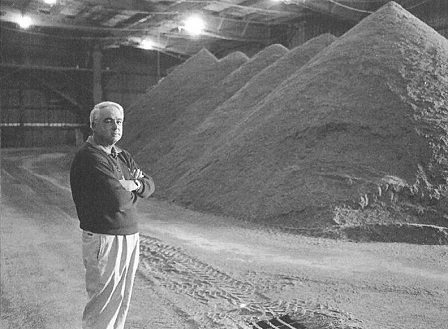

Jule Wheatly surveys a warehouse with piles of fish meal produced from menhaden.

“This boat was built in 1945,” says Wheatly. “It was immediately put in mothballs and never did battle. We bought it in 1972 and converted it to a menhaden boat. We redid it again in 1988.”

Visitors can see the boat as they enter the front of the factory at the guard station on Front Street.

Built at the tum of the 20th century, the plant was bought by Wheatly’s grandfather, C.R. Wheatly, and William Potter in 1934. Jule Wheatly joined the operations in 1973.

“When I came here, there was only one house here and a pond close to the fish factory,” he says.

Now the end of Front Street is lined with rows of new homes and condominiums.

The factory, which has about 75 employees, includes a number of buildings, two wooden piers and a huge net wheel that stretches 300 yards.

“Men used to walk inside and tum the wheel by hand,” says Wheatly. “Now, it has a hydraulic motor.”

The processing begins right after the menhaden catch is brought to the dock. The fish are left on the boat where they are sucked with a pump that then dumps the catch into a raw box shaped like a boat hull. About 1,000 menhaden can be sucked through at one time.

”The technology has improved a lot,” says Ross Goode, who has worked at the plant since 1948. “You used to have to move fish with a fork before they got air hoses.”

Now the fish are ready to be cooked in huge boilers, then sent to large presses where the liquid is squeezed out of the fish.

“We pressed about a million fish last night,” says Wheatly.

During the next process, the liquid goes to a large centrifuge that spins the liquid to separate the water from the oil. The oil is saved in tanks and later sold for cosmetics and other purposes. The bulk of the material goes to a dryer that prepares it for fish meal.

“We can process about 110,000 pounds of fish meal an hour from start to finish,” says Wheatly.

The fish meal, which is high in protein, is then stacked in mounds like small mountains in a warehouse where it is ready to be transported.

Menhaden, which comes from an Indian word meaning “makes things grow,” has a tremendous growth factor, says Wheatly. Indians used the fish as a fertilizer to make corn grow.

The plant’s busiest season is the fall, when menhaden have gotten large enough to be profitable for processing into oil.

In the summer, you only get about one gallon of oil per thousand pounds of menhaden, in comparison to the fall when you get 10 or 11 gallons per thousand, says Wheatly.

The plant closes in mid-January and reopens in April or May when the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries opens the spring menhaden season.

In the height of the season, two vessels run near shorelines. When both crews bring in more than 3.5 million pounds of menhaden, the plant operates around the clock.

“It takes 24 hours to cook 3.5 million pounds of fish,” says Wheatly. “Sometimes we start at Thanksgiving and never stop until Christmas.”

Wheatly hopes to continue to see busy seasons.

“I can’t tell you how many meetings I have gone to, fighting for my plant,” he says.

This article was published in the Winter 2001 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.