By TERRI KIRBY HATHAWAY

Illustrations By CHARLOTTE INGRAM from North Carolina’s Amazing Coast: Natural Wonders from Alligators to Zoes

Readers of a certain age will remember when the book Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask) entered the American mainstream. Published in 1969, this book gave many young people their first taste of sex education. So, I’m using a similar title to give young and old alike a lesson in the reproductive practices of marine and estuarine animals.

There are four survival instincts in the animal kingdom: feeding, fighting, fleeing and … reproducing. Let’s think about the last one: How do animals in marine environments procreate?

There are many questions to consider when thinking about sex in the sea.

- Is it asexual or sexual reproduction? Is there external or internal fertilization?

- Are the sexes separate — with male and female individuals — or do the male and female reproductive organs reside in each individual?

- Do the animals produce a few large offspring or thousands of small ones?

- How do individuals find each other in order to reproduce?

- When is the right time? Where is the right place?

- What environmental cues are guiding factors?

Whew! Is your mind already spinning? Mine is.

Read on for more about sex in the sea — and get ready to learn some new words to impress your friends.

Sex Isn’t Everything

Sea anemone

In asexual reproduction, a single organism produces offspring that are genetically identical to the parent. There’s no fertilization, no egg and sperm, and no need for males and females. It is reproduction without sex.

Comb jelly

Budding and fission — the division of one organism into two — are examples of asexual reproduction. Anemones and hydra, a type of freshwater invertebrate, reproduce asexually, cloning new individuals from a single organism.

Sexual reproduction involves the joining of gametes, the reproductive cells known as the egg and sperm. Each gamete contains one half of the necessary genetic material: When combined, they create one individual that is slightly different from its parents. Most marine and estuarine animals reproduce sexually — including oysters, sharks and whales.

To make things even more confusing, some animals like moon jellies reproduce sexually during one stage of life and asexually during another. Their gametes combine to create planula larvae, which settle on the bottom, grow into a polyp or stalk, and asexually bud baby jellies, known as ephyrae.

True jellies of the class Scyphozoa also exhibit both sexual and asexual reproduction during their life cycle. Similar to moon jellies, the adults broadcast eggs and sperm into the water column. Fertilized eggs start to develop, settle onto a hard surface and grow until they asexually bud ephyrae, which are released back into the water as tiny, free-swimming medusa.

The Ins and Outs of Fertilization

Horseshoe crab

Sexual reproduction can be external or internal. Many fishes and invertebrates shed their eggs and sperm into the water column, an external method called broadcast spawning. The currents transport the reproductive cells around, and somewhere, somehow, they combine to create a zygote, or fertilized egg. Sea urchins, corals, oysters, flounders and eels are broadcast spawners.

Another type of external fertilization involves the male of the species shedding his sperm over eggs laid in a nest by the female. These animals include horseshoe crabs, damselfish and salmon.

A number of aquatic species rely on internal fertilization, the process by which the male places his sperm into the female’s body to fertilize her eggs. Blue crabs, barnacles, sharks, skates and rays all exhibit internal fertilization.

Aquatic Gender Bending

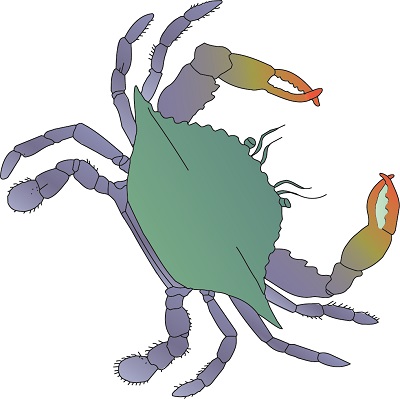

Animals with separates sexes — male and female reproductive organs in different individuals — are called dioecious, which is Latin for two houses. Blue crabs, for example, are dioecious: They have males and females.

Many species exhibit sexual dimorphism, meaning males and females differ in appearance. The difference may be size, color, shape or structure.

Blue crab

With blue crabs, it’s easy to tell the difference between the sexes by looking at the claws and abdomen, also known as the apron. The male has blue-tipped claws and a narrow apron shaped like the Washington Monument, while the mature female has red-tipped claws, often called “painted fingernails,” and a broad apron shaped like the dome of the Capitol Building.

Monoecious — one house — animals carry male and female reproductive organs in one individual. These species also are called hermaphroditic. To complicate matters further, there are sequential and simultaneous hermaphrodites.

Sequential hermaphrodites produce male and female sex organs, but only one set works at a time. These animals start out as either male, called protandry, or female, called protogyny, and then eventually switch genders.

For example, all groupers are protogynous, starting life as females. After producing eggs, groupers gradually change into males.

Anemonefish, like the star of “Finding Nemo,” are protandric. They live in groups with two larger individuals — the larger being female, the other male — and a number of small nonbreeding individuals. If the group loses the breeding female, the breeding male develops ovaries to become the breeding female. One of the nonbreeding fish becomes the breeding male.

Simultaneous hermaphrodites have working male and female reproductive organs at the same time, so any adult can mate with any other adult of the same species.

Self-fertilization by these individuals is rare but not impossible. As simultaneous hermaphrodites unable to move, barnacles must have their eggs fertilized by a neighbor.

The Numbers Game

Leatherback sea turtle

What are the odds of a single oyster egg shed into the brackish sound waters being fertilized? And the odds of it moving through its larval stages, developing into spat, successfully settling onto another oyster and growing to market size? Astronomical is my guess!

That is why oysters and other broadcast spawners produce millions of eggs and sperm. They need that many so at least a lucky few will survive to reproduce.

Each sea turtle nest contains 80 to 120 eggs depending on the species. But just one hatchling out of 1,000 makes it to adulthood to keep the species going.

Other species produce a small number of offspring, spending lots of time and energy taking care of them until they are ready to leave their parent or parents. Think about the whales and dolphins that feed and protect their young for months.

The Right Time and Place

Environmental cues help animals determine the correct time and place for reproduction. Indicators include the phase of the moon, the tidal cycle, water temperature and salinity, and the amount of daylight.

Horseshoe crabs lay their eggs at night during high tides of the new and full moons. Some reef-building corals release their gametes only at night during a full moon. Oysters spawn when the water temperature warms up to around 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

Exceptions to the Rules

Seahorse

Male seahorses fertilize eggs after the female places the eggs in his brood pouch. He holds the fertilized eggs until they hatch.

The male sea catfish is an oral brooder, holding the fertilized eggs in his mouth for two to four weeks, until the young hatch and finish absorbing their yolk sacs.

The males of cartilaginous fishes like sharks, skates and rays use claspers to place sperm inside the female’s cloaca and fertilize the eggs. Depending on the species, sharks and other egg- producing animals can be:

- Oviparous – eggs laid and hatched outside the mother’s body;

- Ovoviviparous – eggs hatched within the mother’s body; or

- Viviparous – eggs develop into embryos, which have an umbilical-type connection with the mother, that result in live birth. Humans are viviparous.

I trust by now you have learned some new words. I also hope you have discovered the breadth and depth of how marine and estuarine animals reproduce.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough space to describe courting and foreplay rituals, the various methods of egg laying, or the many types of egg cases.

Maybe those ideas will spawn a future article or two.

Glossary

- Cartilaginous – having a skeleton made of cartilage instead of bone

- Clasper – modification of pelvic fins of male sharks, skates and rays that transfer sperm to the female’s cloaca

- Cloaca – common opening for intestine, excretory and reproductive systems of cartilaginous fishes

- Dioecious – organisms having separate male and female sexes

- Ephyra (ephyrae) – early planktonic larval stage of scyphozoans (true jellies)

- Gamete – a reproductive (sex) cell, such as sperm, egg or pollen grain

- Hermaphrodite – organism that has both male and female gonads

- Medusa – bell-shaped life stage of cnidarians (sea jellies)

- Monoecious – organisms that contain male and female gonads

- Oviparous – young develop in eggs that are laid outside mother’s body

- Ovoviviparous – young develop in eggs retained within the mother’s body and are born alive

- Planula – ciliated larval stage of cnidarians

- Polyp – a body form that is hollow, elongate and attached to a substrate

- Protandry – the process of functioning first as male, then changing to female (e.g., anemonefish)

- Protogyny – the process of functioning first as female, then changing to male (e.g., wrasses)

- Sexual dimorphism – a difference in appearance between male and female individuals in animals

- Viviparous – young develop inside the mother and are born alive

- Zygote – a fertilized egg

Selected References

- Coulombe, Deborah A. 1984. The seaside naturalist: A guide to study at the seashore. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Hardt, Marah J. 2016. Sex in the sea: Our intimate connection with sex-changing fish, romantic lobsters, kinky squid, and other salty erotica of the deep. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Kaplan, Eugene H. 2006. Sensuous seas: Tales of a marine biologist. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Otte, Jean-Pierre. 2000. The courtship of sea creatures. New York: George Braziller/Publisher.