By E-CHING LEE

For communities in coastal North Carolina, tourism and development present many challenges. Changes often happen quickly, putting stress on local resources.

“You can either have a roadmap or take what you get,” says Pat Long, director of East Carolina University’s Center for Sustainable Tourism, or CST. But to proactively plan — and to plan well — local officials have to consider the expectations of the residents in their county.

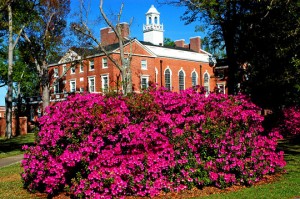

Pender County Courthouse in Burgaw. Photo courtesy Pender County Tourism.

That’s where Long and his colleagues come in. With funding from North Carolina Sea Grant, the research team surveyed owners of single-family homes in Brunswick, Currituck and Pender counties. Owners were asked about the impacts of tourism on their quality of life, including the economy, services, environment and cultural opportunities.

The questionnaire was sent to full-time residents and second-home owners, defined as people who own property in these counties but have a permanent address elsewhere.

Overall, Long says the results show strong support for sustainable tourism practices and provide a positive assessment of tourism. The data also show some similarities between the opinions of full-time residents and second-home owners.

In fall 2011, the CST team presented their findings to stakeholders in the three counties.

And they continue to tailor specific versions of the overview for interested groups, such as an October presentation to tourism officials in Pender County and another to Currituck County stakeholders in January. The team is also working on a comprehensive combined report and plans to host a related webinar in the spring, with support from Sea Grant.

“It is gratifying to see university research help coastal residents make decisions. That’s what Sea Grant’s research program is all about — useful, science-based information,” says Jack Thigpen, Sea Grant’s extension director.

HAVING A VOICE

“Previous studies focused on visitors and local residents,” says Huili Hao, CST research director. A unique part of this study was the inclusion of part-time residents who owned second homes at the coast. These property owners have made a substantial investment in the community, but they were typically not part of the local decision-making process because they could not vote in local elections.

The researchers chose these three counties because they shared several similarities. First, although tourism is a major industry, there still is room for growth. Next, their coastal locations result in competition for limited resources, such as beachfront locations, and makes them vulnerable to climate change effects, such as sea level rise. Finally, the counties have a substantial number of homes owned by non-full-time residents.

“We wanted to know about the experience of the population, with attention to the current and future look of tourism in the county,” explains Whitney Knollenberg, whose master’s thesis was based on this study. Residents must support tourism for it to grow. Second-home owners provided an additional perspective on tourism development issues.

The Cape Fear River at Lane’s Ferry Crossing, which is now the N.C. 210 Bridge. Photo courtesy Pender County Tourism.

To develop the survey, the team conducted site visits and meetings with stakeholders in the target counties. “It allowed us to cover issues they thought were important,” Knollenberg says, as well as to build relationships with people who would be using the study results.

The CST team mailed invitations to property owners to complete the survey. Local tourism, planning and economic development officials, as well as some wellconnected residents, assisted the team by encouraging a good response from the community. The questionnaire could be completed online, over the phone or on paper.

Hao’s phone number was listed if participants wanted to receive a copy of the questionnaire. Many of the requests for paper surveys came from the second-home owners. Often, the conversation expanded beyond the request. These property owners discussed other community issues.

“Second-home owners want to be heard by the local government,” she notes, explaining that many treated the phone call as an opportunity to make their opinions known.

Hao and the CST team found that the second-home owners had a strong sense of community and concerns about sustainable development.

Long notes that these residents often had property that was closer to the ocean or estuarine waters, making them more concerned about the intensity of storms, sea level rise and flooding than full-time residents. Overall, as a group they strongly supported tourism development in these communities.

NEIGHBORS, ONE AND ALL

“Research is just king,” says Monique Baker, director of the Pender County Tourism Department, noting that studies on tourism are rare and expensive. “Residents, whether they be full-time or second-home owners, seemed very open and friendly to tourism development, as long as there is no real negative impact.”

That’s promising because Baker sees the need to provide more attractions, lodging, restaurants and shopping to bring tourists to Pender County. She also hopes that developers will take note of these opinions and work to build those amenities in the parts of the county that lack them.

“The island is the big attractor,” Baker acknowledges, referring to Topsail Island, part of which is in Pender County. But there are locations farther inland, such as Burgaw where she is based, that would benefit from more tourist facilities.

Poplar Grove Plantation. Photo courtesy Pender County Tourism.

The responses of full-time residents and second-home owners in Pender County were fairly positive, Baker notes. However, the full-timers were, in her opinion, more realistic and had lower satisfaction levels, while the second-home owners were more idealistic and positive. The difference, she surmises, is because the latter group lives elsewhere part of the time and is not subject to daily life in the county.

“Full-time property owners are here all the time and they know what does and doesn’t happen,” says Allan Libby, director of the Surf City Tourism Development Authority. He points out that year-round residents are more sensitive to the changes and difficulties of island life.

For example, the bridge that connects Topsail Island to the mainland opens at certain times to let watercraft through. Drivers often get “caught behind the bridge,” waiting for it to close to get on or off the island, Libby explains. Full-time residents have learned to build extra time into their daily routines but the delays, particularly when island traffic gets very busy in the summer, can become an annoyance. Second-home owners, who do not face this inconvenience regularly, are more likely to see this as part of the charm of island living.

And island dwellers, year-round or not, have different perceptions than those who live on the mainland. According to Libby, major development on the island, such as a fast-food restaurant or a big-box store, would not be well received. But he thinks that a good compromise is to maintain the character of the island, yet allow some large, off-island growth. This might give residents and visitors more choices about where to eat, what to do and where to go.

“And people love options,” he stresses.

PROVIDING ALTERNATIVES

Kyle Breuer looks at the survey from another perspective. As the director of Planning and Community Development in Pender County, he seeks to balance the demands of tourism with the needs of the everyday population.

Breuer wanted to know what his organization could do to make sure development patterns continued to maintain the high quality of the natural environment in Pender. He also appreciated public feedback on land-use perspectives from non-full-time residents.

He thinks that the opinions expressed in the questionnaire might affect how the county deals with air and water quality issues, low impact development, treating stormwater runoff and reduced lot sizes. Breuer also theorized that the responses might benefit the development of parks and recreation opportunities in Pender County as alternatives for those who wanted non-beach activities.

“When we do planning, we have this data now to incorporate,” he says, also noting that the data could be used to develop policy in the future.

Holly White, senior planner in the Currituck County Planning Department, also expects possible long-term benefits from this study. She foresees that the results could be used to guide growth, policy development and long-range planning in the county.

“All the research that Pat is doing would benefit us as we do the Unified Development Ordinance rewrite,” she adds. White was involved in the study from the site visit stage, helping the CST researchers connect with stakeholders in Currituck County communities. She also has participated in the Currituck Goes Green initiative with North Carolina Sea Grant staff.

“Survey results may be a benefit to help the study of the off-beach area,” White continues, referring to the beach areas along the Northern Outer Banks that are open only to four-wheel-drive vehicle access. “This study would tie in nicely.”

White values the sustainability of the community, allowing the county to develop while preserving what attracts visitors. Like Breuer, she also expects that the results will help the county develop a parks and recreation development plan that meets the needs of the residents and tourists alike.

DIFFERENT VIEWS

“The people who live here are not negative toward tourism,” says Will Taylor, a Currituck County resident since 2006 and a volunteer firefighter. “I’m glad to see that came out.”

Local residents benefit from tourism, he says. “Everyone knows the need for good tourism. It keeps our taxes down and provides many other things,” such as good restaurants, and local entertainment and shopping venues.

Anglers and visitors enjoy the activities at the Surf City pier. Photo courtesy Pender County Tourism.

But not all full-time residents are alike, Taylor acknowledges. He notes that Currituck County residents on the Outer Banks islands are mainly retirees, while the people on the mainland still are in the workforce.

Josh Bass, president of the Currituck Chamber of Commerce, lists three distinct populations in Currituck County: full-time residents on the mainland, second-home owners and what he calls “resort residents” who live full time in the communities on the Outer Banks. “I thought they were a more cohesive group,” he says, but was surprised at the difference among them.

And that’s where graduate student Doug Peterson comes into the picture. He is breaking down the results of the study geographically through a spatial analysis. In land-use planning, geographic and spatial aspects and information are the most useful.

The study received responses from full-time residents and second-home owners from the coast to the inland areas in each And island dwellers, year-round or not, have different perceptions county. In the first pass, Long and Hao looked at each county as a whole.

But now, they want to break down the results even further.

“We know how they responded. We know where they are located.

Now we want to know how they responded to a specific question, as a group, by location,” Peterson explains. He is trying to reveal if people within a particular location are more concerned about a specific topic.

Hao wants to determine the potential of support for second-home and sustainable tourism development based on location of the respondent’s property. She expects that subcommunities within the counties surveyed will have varying satisfaction levels for different things.

“Burgaw,” Hao observes, “is different from Surf City.”

She also anticipates that residents will have a different sense of risk based on the location of their property. “Second-home owners” — and even full-time residents — “along the coast are different from those who live on the mainland,” she says.

Island living — or coastal living, for that matter — is not for everyone, warns Surf City’s Libby.

“You’ve got the dream and you’ve got the reality,” he says. But the trick is to find the happy medium that exists between the two.

“Do your homework very, very carefully before committing to coastal living,” he advises.

For more information on this study, go to: www.ecu.edu/cs-acad/sustainabletourism and follow the link for Center Initiatives and then Community Sense of Place. Also, check this site for details on a related webinar scheduled for spring 2012.

Visit ncseagrant.org/s/real-estate to view a brochure: Questions and Answers on: Purchasing Coastal Real Estate in North Carolina.

This article was published in the Winter 2012 issue of Coastwatch.

For contact information and reprint requests, visit ncseagrant.ncsu.edu/coastwatch/contact/.