By MIKEY GORALNIK

Mikey Goralnik is a concurrent degree student in the Master’s of City and Regional Planning program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Master’s in Landscape Architecture program at North Carolina State University. He has worked at the UNC-CH Institute for the Environment, the UNC-CH Coastal Hazards Center and the Louisiana State University Coastal Sustainability Studio. He studies the connections between hazard mitigation, climate-change adaptation and smart-growth planning practices, with a focus on economic development and social justice. The 2014 recipient of the Wendy L. Olson Award for Public Service in Landscape Architecture from NC State’s College of Design, Goralnik holds a bachelor’s degree in American studies from Tufts University.

When we first discussed our ideas to apply for the 2014 North Carolina Coastal Policy Fellowship, my landscape architecture faculty mentors, Andrew Fox and David Hill, and I were pretty confident that, if nothing else, the letterhead on our proposal would read very differently than those of most other applicants.

Mikey Goralnik. Photo courtesy Mikey Goralnik.

After all, we are from the North Carolina State University College of Design, not a program one would typically associate with coastal policy.

In our view, most of the work being done to cultivate a more sustainable coast — in North Carolina and elsewhere — occurs in traditional hard science fields. In many ways, this division of labor makes perfect sense. Fields such as oceanography, meteorology and wildlife biology, including research by Kimberly Hernandez, my 2014 Coastal Policy Fellow counterpart, are imperative for tangibly improving the welfare and sustainability of coastal life as we know it. It would be difficult to overstate how important thinkers in these fields are to solving the perplexing environmental and social riddles that cloud the future of coastal North Carolina.

But to us, despite their potential to offer equally critical solutions to coastal dilemmas, architecture, landscape architecture and engineering are woefully underrepresented in conversations around North Carolina’s coast. While work in the traditional hard sciences is, and always will be, a foundational component of the state’s coastal future, we believe that achieving truly resilient communities — places that can both absorb the impacts of the extreme events of the future and address their present day causes — cannot happen without more committed dialogue from and with the design fields.

How can design help? Yes, we are responsible for constructing the buildings, altering the landscapes, and to an extent, determining the development patterns that both influence and can — or cannot — withstand the impacts of climate change, sea-level rise and the more powerful coastal storms of the future. From erosion and scour to groundwater and soil contamination, sitework, construction and land-use practices can have profound impacts on the nonhuman and human communities of coastal North Carolina.

But design’s contributions to a resilient North Carolina coast can go deeper. Our ability to achieve stronger buildings and spaces directly emanates from both a process and set of inalienable values that define the design fields, and can be instrumental in ensuring the resiliency of coastal North Carolina. The ability to think abstractly, iterate and test unconventional ideas, modify, and then doggedly reapply them are by no means the exclusive domain of architects, landscape architects and engineers. However, the application of this process in a collaborative and interdisciplinary setting is, in our view, a potentially transformative element of the designer’s unique toolbox.

Central to design work and education is the studio, a hive of creativity where ideas are both actively shared and passively absorbed. The studio setting, where complex analysis and innovative risk taking aren’t just celebrated, but required, is where designers learn how to innovate and collaborate in ways that are unconstrained by what is fashionable or, in some cases, even possible — yet. The studio is, in other words, where the resilient structures and spaces of today begin. More importantly, it is where the answers to the as-yet unasked — and unknown — questions of the future are hatched.

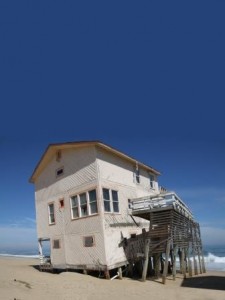

Goralnik argues that smart design is an important element of a sustainable coast. Photo courtesy Mikey Goralnik.

This chaotic environment tends to resist constraint, but Fox, Hill and I pursued the Coastal Policy Fellowship to help guide the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab, or CDDL. This brand-new interdisciplinary studio course, offered by the NC State College of Design, consists of a seminar in one semester and a studio in another. As Hill explains, the CDDL functions as “a bridge between science and communities, seeing through a designer’s eyes, and helping others imagine various scenarios for the conditions that they live in.”

The CDDL immerses students in the unique ecological and demographic contexts that both complicate and facilitate the pursuit of a more resilient coast. View the course website at design.ncsu.edu/coastal-dynamics-design-lab/.

In addition to experiential curriculum, design students get a hefty dose of the local, state and federal policies at play in coastal North Carolina. My work is intended to ground designers in the web of policies, concepts and existing governance frameworks that determine the shape of design interventions in coastal communities. This helps ensure that the studio’s explosion of transdisciplinary ideas will translate into realistic, feasible and tangible improvements in the built and environmental conditions of our state’s coast.

But while the actual design solutions — the buildings, spaces and infrastructure networks — that emerge from the Coastal Dynamics studio in the Fall 2014 semester are some of its most critical outcomes, familiarizing young designers with the state’s coastal issues may ultimately be its most constructive contribution.

By equipping interdisciplinary thinkers with an understanding of and appreciation for the challengingly complex and singularly compelling questions surrounding coastal North Carolina, students come away with the techniques needed to propose solutions that can adapt and change as quickly as the coast.

As CDDL student Bridgette Cannon reflects, “The exchange of knowledge between the architecture and landscape architecture departments is priceless.”

I agree, for this semester’s academic projects — and for the future of applied work on behalf of coastal North Carolina.

For Goralnik’s full report, contact Lisa Schiavinato at lisa_schiavinato@ncsu.edu.

This article was published in the Autumn 2014 issue of Coastwatch.