Recreational crabbers play a role in responsibly harvesting crabs and managing gear.

• LEFT: A blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. Photo by jere7my tho?rpe/flickr/CC BY NC-SA 2.0. • RIGHT: Recreational crab pots require a pink buoy. Photo by Vanda Lewis.

BY JULIE LEIBACH

Blue crabbing with family and friends is a popular coastal North Carolina pastime. And there’s more than one way to catch a crab. So-called “chicken-neckers,” for instance, tie a weighted string around — you guessed it — a chicken neck (or other bony part) and drop it in the water. Others sneak up on their catch with a dip net. But many people set a pot and check back later for the goods. If you prefer the pot, read on for more information on harvesting and gear management.

Know Your Crab

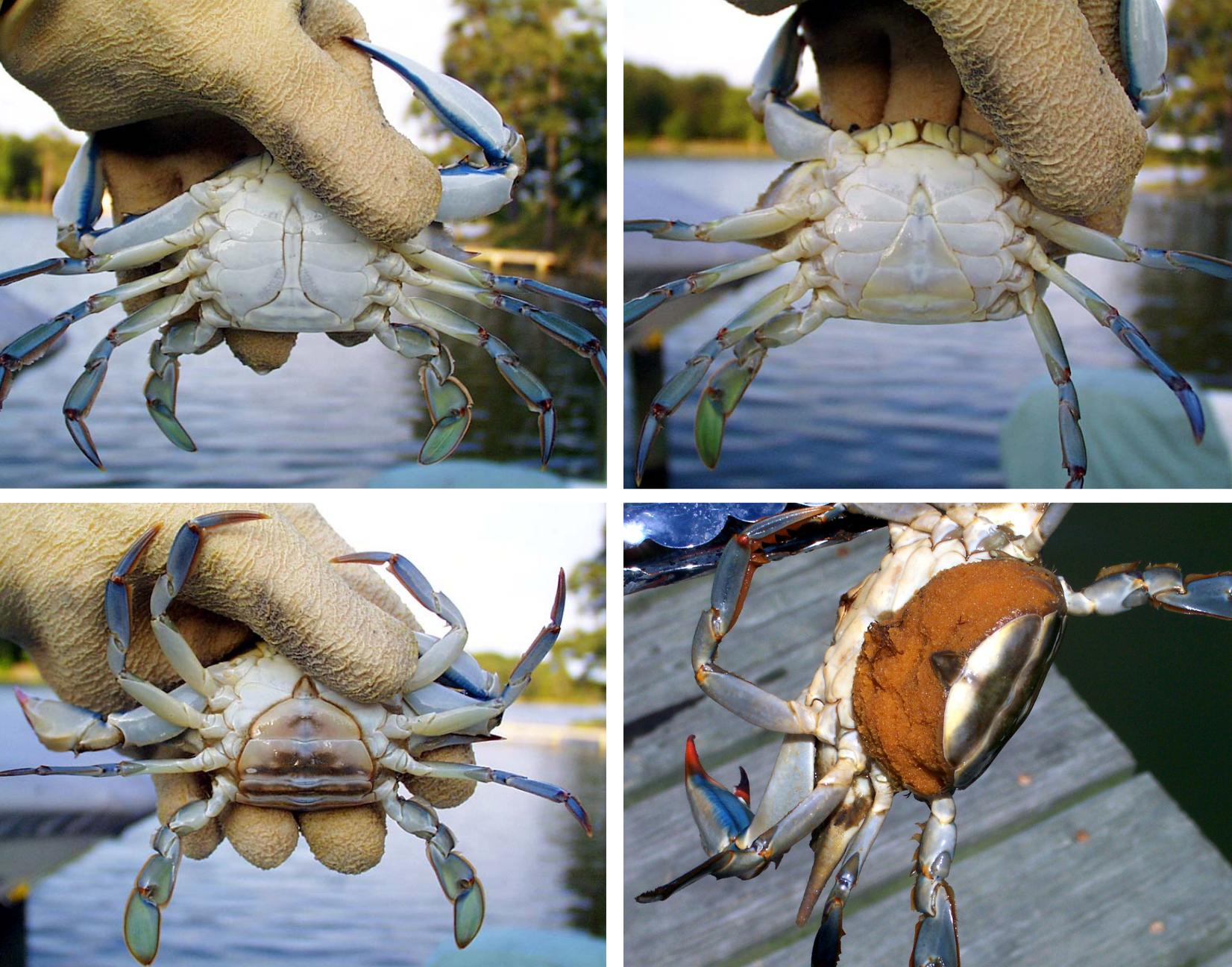

Lower-right photo by David Saddler/flickr/CC BY 2.0; all other photos by Steven C. Zinski/bluecrab.info.

UPPER LEFT: • Sex: Male • Nickname: “Jimmy” • Claws: Blue • Abdomen: Washington monument shape • Harvest limit: Legal minimum size is five inches

UPPER RIGHT: Sex: Immature female • Nickname: “Sally” or “she-crab” • Claws: Red tips • Abdomen: Pyramidal shape • Harvest limit: Unlawful to take

BOTTOM LEFT: • Sex: Mature female Nickname: “Sook” • Claws: Red • Abdomen: Capitol dome shape • Harvest limit: No size limit

BOTTOM RIGHT: • Sex: Female with eggs • Nickname: “Sponge crab” • Claws: Red • Abdomen: Covered with yellow-orange, brown or black egg mass • Harvest limit: Outside of April, all sponge crabs legal; in April, only sponge crabs with a yellow-orange egg mass are legal.

Harvest limits above apply to hard-shell crabs.

Before harvesting blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus), know which ones are legal to keep. A crab’s sex and general age can be determined by the color of its claws and the shape of its abdomen, or apron. Crabs are measured from point to point across the widest part of their shell, or carapace.

Tending Your Pot

As a recreational crabber, you can set one pot without a license. You can set up to five with a license.

Based on data from coastal recreational fishing license holders, recreational crabbers brought in an average of nearly 31,400 pounds of crab a year from 2011 to 2017, according to the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries. The amount doesn’t account for crabbers fishing without licenses, however.

While that number is hard to pin down, a 2002 survey by researchers at East Carolina University and supported by North Carolina Sea Grant indicated that about 5,500 recreational crabbers who were legally fishing without licenses hauled in close to 280,000 pounds.

By comparison, the commercial blue crab harvest averaged over 27 million pounds annually from 2008 to 2017.

“Recreational crabbers represent only a tiny fraction of the harvest and pots in the water, when you compare it with commercial enterprises,” says Gloria Putnam, North Carolina Sea Grant’s coastal resources and communities specialist. “But each of us — every angler, crabber — has the opportunity to contribute to resource and seafood conservation through attentive gear practices.”

The beauty of a crab pot is that you can walk away from it for a while. But don’t set it and forget it. Instead:

- In addition to your buoy, mark your pot with your name.

- Use enough line so the pot stays submerged at high tide.

- Check pots daily, if possible, but at a minimum of every 5 days during daytime hours.

- Bring in gear before a big storm and before you leave the property.

- Remove your pot during the blue crab fishery closure, which in 2020 is Jan. 15 through Feb. 7, unless otherwise indicated. Note that in some areas, pots may not be set from June 1 through Nov. 30. See designated pot areas.

For a full list of recreational crabbing regulations, check the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries’ website. Look for the Recreational Crabbing tab, and select Regulations and Requirements. Regulations can change, so check back periodically.

Vanquishing Ghosts

Ever heard of derelict fishing gear? The term refers to gear such as pots, nets and lines that have become lost or otherwise discarded. Globally, derelict gear appears to be the main type of submerged marine debris, according to several surveys on the subject.

A commercial fisherman recovers a crab pot during the N.C. Coastal Federation’s Lost Fishing Gear Recovery Project cleanup. Photo by Chris Hannant.

Various causes lead to rogue crab pots, such as storms; rope and buoys in poor condition; entanglement with boats; and inappropriate disposal. Once lost, those pots can pose navigational hazards, as well as damage sensitive habitats such as seagrasses and marshes.

Derelict pots also can continue trapping crabs, potentially luring them away from pots that crabbers regularly check. They can attract other species, too. For example, during a 2018 crab pot cleanup effort in N.C. coastal waters, participants found more than 2,400 blue crabs and more than 760 finfish enmeshed as bycatch in nearly 3,000 pots. Retrieval efforts elsewhere have documented organisms including birds, river otter and diamondback terrapin, among others.

Diamondback terrapins are small turtles native to estuarine environments along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to Texas. In North Carolina, they’re a species of special concern. Both active and derelict pots can capture and drown these reptiles, which in the summer can only hold their breath for 45 minutes.

Creatures that have succumbed to derelict crab pots can become bait for other organisms, fueling a cycle known as “ghost fishing.”

Preventing gear loss is the best way to minimize the impacts of ghost fishing. But once gear has disappeared, then what? There are various ways to improve retrieval, including using sonar to detect derelict gear, as well as organized cleanups.

Inspired by crab pot recovery efforts by the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries’ Marine Patrol, in 2014 the North Carolina Coastal Federation launched the Lost Fishing Gear Recovery Project, hiring local commercial fishermen to retrieve derelict pots during the annual fishery closure. Initial funding came from North Carolina Sea Grant and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program.

The project expanded statewide in 2017, thanks to funding from the N.C. General Assembly, administered by North Carolina Sea Grant. The state directly funded the 2018 and 2019 cleanups.

In 2019, nearly 80 participants removed more than 3,000 crab pots from coastal N.C. waters.

Seafood Safety

Once you’ve got your blue crab haul, what next?

Store live crabs at 40 to 50°F until ready to cook. If you’re using a cooler, place three to four inches of ice at the bottom and cover with a barrier, such as plastic foam or waxed cardboard with holes punched in it, or a burlap sack.

Place your crabs belly-down on the barrier and loosely cover them with damp burlap or a cheesecloth. Leave the cooler lid ajar for air circulation.

Cook crabs the same day they’re caught. Never eat dead crabs — bacteria can quickly accumulate. Live crabs will show leg movement even at cool temperatures.

For blue crab recipes, check out marinersmenu.org. Janna Sasser and Gloria Putnam contributed research.

This article was published in the Summer 2019 issue of Coastwatch. Click here for reprint requests. Or, download a copy of this article.